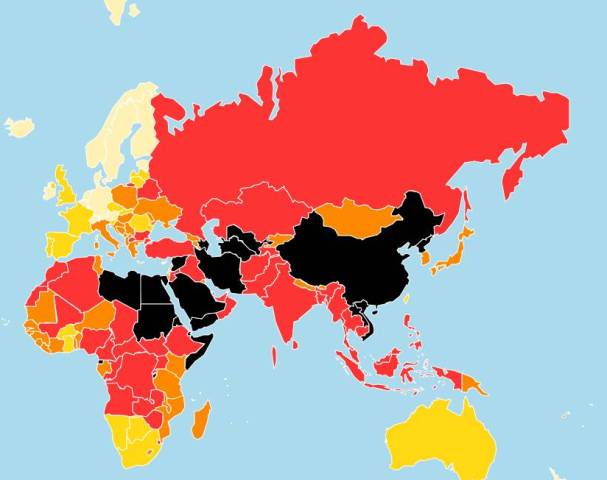

India ranks 136 out of 186 in the media freedom index published by Reporters Sans Frontières (RSF). [source: RSF]

India ranks 136 out of 186 in the media freedom index published by Reporters Sans Frontières (RSF). [source: RSF]

[An excerpt from an opinion piece by journalist and film maker Nupu Basu in the special edition on media freedom of The Round Table: Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs.Opinions expressed do not reflect the position of the Round Table.]

On 5 September 2017, a well-known 55-year-old woman journalist, Gauri Lankesh, who edited a Kannada weekly, Gauri Lankesh Patrike, was shot dead outside her home in Bangalore by gunmen mounted on motorcycles. The assassination sent shockwaves across the country, and led to widespread public protests. It was also condemned globally and at the United Nations.

This murder demonstrated, as never before, the real threats that journalists face in modern-day India. Gauri Lankesh’s murder, coming on the heels of a number of attacks on journalists, liberal thinkers, rationalists and whistle-blowers in recent months, marked a flashpoint in the debate on freedom of the media in a country that likes to describe itself as a vibrant democracy. Gauri had been a vocal critic of the communal politics seen to be pursued by the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and its controversial affiliate, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh.

The media in India have completely metamorphosed from their early moorings in the country’s freedom struggle. Attacks on Indian journalists and restrictions on freedom of expression are not new phenomena. Many journalists bear the scars of the censorship regime imposed by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi during a dubious state of emergency in 1975–1977. The BJP is now, in the view of some, informally using the same pressure tactics. Hypernationalism being propagated by sections of the media, particularly television, reflects the flavour of India’s present politics. Investigative journalism is also frowned upon. This, in turn, is posing a threat to freedom of expression as a whole, with self-censorship on the rise.

Rajdeep Sardesai, senior journalist and consulting editor with India Today Group, has attributed the decline of press freedom in India to multiple factors: ‘A deadly combination of an authoritarian political leadership, a craven media ownership and an enfeebled journalistic community are locked together in a tap dance’. The tragedy, Sardesai points out, has played out because ‘the institutional challenges that would resist an assault on press freedom have weakened’.

Overall, media freedom index figures for India are deeply disturbing. India ranks 136 out of 186 in the index published by Reporters Sans Frontières (RSF). During the first nine months of 2017, eight journalists had been killed. Sevanti Ninan, founding editor of The Hoot, has commented:

The major challenges are coming from seeing the internet as a threat to internal security, leading to internet shutdowns in the states of India becoming chronic; from the increasing vulnerability of journalists, particularly those in the regional media, and from the government’s use of colonial laws such as sedition against Facebook posts, and other kinds of free speech that they see as provocative.

Ninan identified various perpetrators: criminal elements among politicians, whom the police are wary of acting against; and right-wing elements, under the protection of the ruling party, who attack journalists who report on attacks on minorities and other disadvantaged groups.

Freedom of the media in India now merits the description ‘precarious’ for structural and political reasons: liberalisation of ownership, a dramatic proliferation of media platforms, a ‘Murdochization’ of commercial satellite channels, and the insidious production of news in search of circulation figures, away from serious investigative journalism. There has also been increasing political interference in the appointment of editors, targeting those who are deemed to be dissenters, such as Siddhartha Varadarajan at the family-owned The Hindu newspaper. Once known for its credible journalism, today The Hindu is just another paper struggling to keep pace with the circulation battle. Varadarajan went on to set up a website, The Wire, now regarded as a place for objective and independent journalism. Its robust critique of the ruling elite prompted the son of the BJP party president Amit Shah, Jay Shah, to file a criminal defamation complaint against the website in October 2017. The website had relied on public documents to show that Jay Shah’s income had gone up by 16,000 times in the years that Narendra Modi has been the prime minister of India.