[This excerpt is from a book review appearing in The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs.]

At one stage immediately after its release it appeared that this book would become the subject of a restraining order from the Malaysian judiciary, given the large – and fast-growing – number of legal threats that were made for its suppression from within the country. Among those lining up to condemn the book were a former prime minister, a former senior judge (who was also the author’s immediate predecessor in the office of Attorney-General) and a former solicitor-general, all of whom found the contents of the book defamatory of themselves. In the event, none of the fears about injunctions materialised, which meant that readers within and outside Malaysia are free to savour the delights of this exceptionally frank and hard-hitting memoir.

Thomas was catapulted into prominence – and controversy – in the immediate aftermath of the momentous 2018 general election which saw the decisive rout of Malaysia’s once-invincible UMNO coalition which had held continuous power for 61 years since independence from British rule and the return, from retirement, of the 92-year-old former strongman Tun Mahathir Mohamed. In a move which was as unexpected as it was contentious (at least to a large section of Malay nationalists), Mahathir appointed Thomas to the sensitive position of Attorney-General, making him the first ever non-Malay and non-Muslim to occupy that seat (Thomas is Indian by ethnicity and Christian by religious background) as well as the first direct appointment from the practising Bar. So delicately poised was the appointment that Mahathir himself, alleges Thomas in this book in a bombshell revelation, began having second thoughts about it within less than a day after the Yang di-Pertuan Agong, Malaysia’s ceremonial head of state, had given his assent:

The rug was immediately pulled from under my feet. Tun [Mahathir] dropped a bombshell. Despite the Agong’s decision, Tun wanted me to resign because of the scale and magnitude of the Malay opposition to my appointment. I was utterly astonished. Tun wanted my resignation the next day. The professional opportunity of a lifetime had slipped out of my fingers before I could even take a breath. (p. xix)

Fortunately for Thomas, Mahathir’s nerves had been steadied shortly thereafter by, among other things, a reassuring statement from the country’s hardline Islamic party to the effect that they had no objection to Thomas’ appointment. It was under such shaky circumstances that Thomas assumed office as Malaysia’s eighth chief law officer.

Given that UMNO’s drubbing at the polls had much to do with a series of gargantuan financial scandals in which many of that coalition’s leading lights, including the ousted prime minister, Najib Razak, had been implicated, Thomas soon had to deal with calls for a series of challenging prosecutions. He had a few wobbles with these which are described with reasonable candour.

Outside recent controversies, the book also contains revelations on historic issues that, in the context of the febrile state of inter-racial relations in Malaysia, are fairly touchy and provocative. Sample this passage about the involvement of two leading figures, the then deputy prime minister Tun Razak and the then chief minister of Selangor State, in the 13 May 1969 racial riots which marked a turning point in Malaysia’s political development:

[I]t is difficult to believe that Tun Razak did not at least acquiesce in the face of the large gathering of youths of one race shouting and screaming abuse at other races at the residence of Harun Idris, from where they left to begin their acts of terror. What has never been disputed from that moment is that they started from Harun’s house. But was he charged? Absolutely not. He advanced in the UMNO hierarchy, and only when he posed a threat to Tun Razak was Harun investigated. He was charged by the Hussein Onn administration, found guilty of corruption and incarcerated for years. But it was not for his direct involvement in May 13th or aiding and abetting the rioters. (p. 29)

Even more provocatively, Thomas has explicitly stated that the riots amounted to a ‘coup’ by Tun Razak who became prime minister a year later. Statements such as these have, unsurprisingly, touched a raw nerve in elite Malay circles and led some of the grandees to launch an offensive against Thomas. Nazir Razak (son of Tun Razak and brother of Najib), for instance, immediately branded Thomas’s remarks ‘pure conjecture’ for which there was ‘not a shred of credible evidence’. A serving UMNO office-bearer lodged a police complaint accusing Thomas of sedition, criminal defamation and breach of the Official Secrets Act. The fate of that complaint (and a few others) is yet to be determined.

Given that Malaysia’s existence as an independent nation has been more or less co-terminus with the author’s life, there is much in the book by way of commentary, even analysis, on the momentous events that have determined the course of the country’s evolution over the past half a century. Arguably, the most consequential of these, at least insofar as the state of the rule of law is concerned, was the ‘judicial crisis’ of 1988 which led to the emasculation of the judiciary – an event whose reverberations continue to be felt to this day. Thomas, who had a ringside view of that event, albeit as a relatively junior lawyer, offers an account which is at least as worthy of attention as those offered by other observers. Unsurprisingly, that account is characterised by forthrightness of a high order.

Venkat Iyer is the Editor of the Round Table Journal.

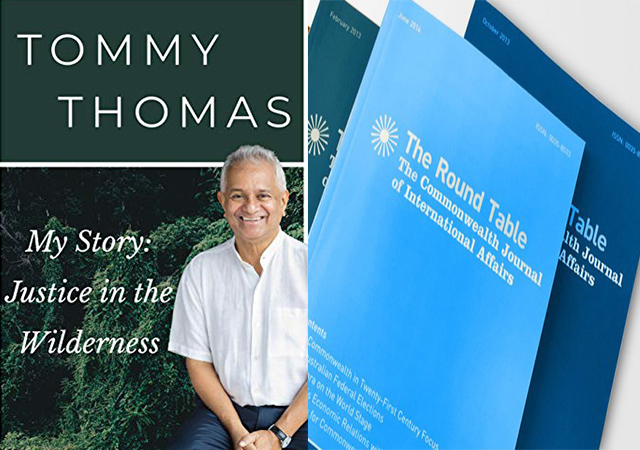

My Story by Tommy Thomas, Petaling Jaya (Malaysia), Strategic Information and Research Development Centre, 2020.