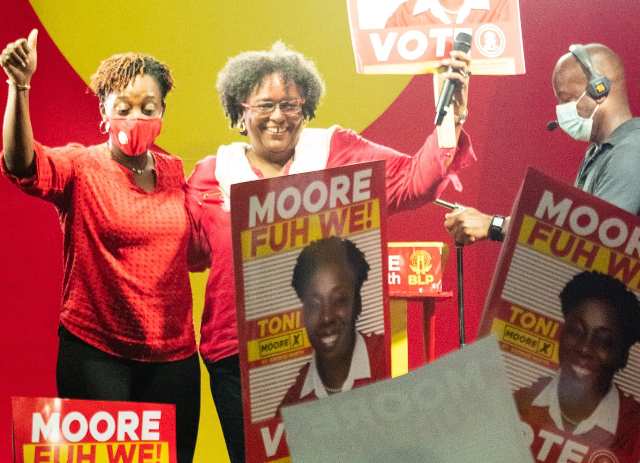

Mia Mottley campaigning in Novemeber 2020 for candidate Toni Moore (left). [photo: BLP Facebook page]

Mia Mottley campaigning in Novemeber 2020 for candidate Toni Moore (left). [photo: BLP Facebook page]

[This is an excerpt from an article appearing in The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs.]

The Barbados Labour Party recently held a political rally for a by-election at Charles Rowe Bridge, St. George on Sunday 1 November 2020. This rally was important because during this event all speakers were women. They included Dame Billie Miller, Ambassador Liz Thompson, former Consulate General to New York Jessica Odle-Baril, Ministers Sandra Husbands, Cynthia Forde, Marsha Caddle, Santia Bradshaw and Kay McConney, Deputy Speaker of the House Dr. Sonia Browne, candidate Toni Moore and Prime Minister Mia Amor Mottley. The by-election was held on 11 November 2020 and Toni Moore, the BLP candidate won the St. George North seat.

Political meetings and platform speeches are an important and exciting aspect of the Anglophone Caribbean’s political culture. They provide politicians with direct contact to voters and an opportunity to articulate important national as well as local issues. In this by-election, different political meetings were organised by the two established political parties, the Barbados Labour Party (BLP) and the Democratic Labour Party (DLP). This meeting by the BLP provoked a backlash from within the party and outside the party because of the ‘all female cast’. This is instructive and speaks to the male-dominated political culture as well as persistent gender stereotyping of politics as a man’s activity. This despite Mia Mottley becoming the first female to hold the position of Prime Minister in 2018. The optics of female leadership seems encouraging, but society is still very patriarchal, and the political landscape is far from being gender balanced.

Representation is at the core of democracy and has evolved over time to include different groups. Historically, the design of democracy and representation excluded women. There have been very few if any spaces for association for women politically and they tended to be restricted to playing private and/or supportive roles in the region. According to Hinds ‘Although women were active in the labour movement in the 1930s and 1940s, they tended to play supportive roles while these organisations were run by males and often centred around male employment …’ (2007). Moreover, inbuilt disqualifications prevented women from participating in national politics, but they found other spaces to make their mark. In the decolonisation and post-colonial periods, despite legislation that allowed participation, women still found themselves marginalised in the political sphere and excluded from decision-making processes because of the patriarchal male-dominated system that embodied political administration. The extension of the franchise to all women consequent on the declaration of Universal Adult Suffrage transformed politics in Barbados by increasing the voter base, to both males and females. However, women’s political participation largely involved casting of votes and there was a dearth of women’s involvement at other levels of the political process, mainly the decision-making levels.

Currently, the Caribbean is not the only space characterised by this underrepresentation of women; it is a worldwide phenomenon. This underrepresentation is reflected in ranking data from the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) showing low percentages of female representation in Parliament since the 2018 elections in Barbados. There is 23% representation in the Lower House with 7 out of 30 seats and 38% female representation in the upper house with 8 out of 21 nominated positions. This is against a background across the region where women, by and large, do not hold more than 30% of elected positions. Prime Minister Mottley in presenting on challenges to women’s political representation in the Caribbean stated, ‘The reality of [party] membership is that more women are activists, more women are members, but fewer women have the opportunity to choose or decide anything, because it is a closed shop of decision-making’.

Different countries have used different strategies to encourage opportunities for women entering the political decision-making process.

Sandra Ochieng’-Springer is a Lecturer at the Department of Government, Sociology, Social Work and Psychology at the University of the West Indies, Cave Hill Campus, Barbados.