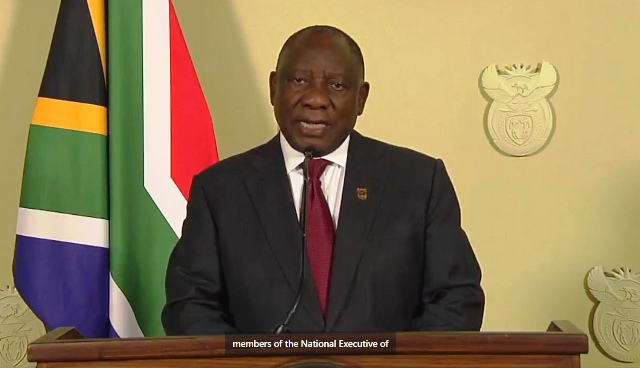

President Cyril Ramaphosa announces his new cabinet. [photo from South African government video]

President Cyril Ramaphosa announces his new cabinet. [photo from South African government video]

A considerable amount of media coverage has been devoted to the outcome of the South African elections since the 29th May poll. It should be acknowledged that it was, overall, a fair and accurate reflection of the political aspirations of the population, despite issues that would have been strongly contested in other democracies. These included President Cyril Ramaphosa awarding himself a half-hour prime-time slot on national television on the eve of polling, and the state broadcaster refusing to run an opposition advert, despite being ordered to do so by the regulator.

The election saw the ANC leadership lose overall control for the first time, winning 40.18% support, against its nearest rival, the Democratic Alliance, with 21.81% backing. (The newly formed MK party, led by former President Jacob Zuma, has taken over the EEF’s role as ‘top disruptor’ ; MK took approximately 12% of the national vote, and performed particularly well in KwaZulu Natal where it polled about 44% to the ANC’s just under 19%.) Under the country’s Proportional Representation constitution the ruling ANC party had no choice but to seek alliances, at national and provincial level. Much against its will, the ANC leadership entered into negotiations leading to an alliance initially signed with the DA and the Inkatha Freedom Party (which had taken 3.85% of the vote). Together they had more than enough support in Parliament, but the ANC, wishing to dilute their influence of brought in other, much smaller parties, some with only one or two members of parliament. Finally, on 23 June, the ANC announced it would form a Government of National Unity (GNU) with ten of the eighteen parties with seats in the National Assembly.

This was just the initial phase of the negotiations. A decision on the allocation of cabinet seats was still required, and this left the choice essentially in the hands of President Ramaphosa. The president, who cut his teeth as a union organiser and was one of the key negotiators in the transition to black majority rule in 1994, proved immensely difficult to deal with, since he was caught between competing factions within his own party. In some cases, Ramaphosa went back on earlier offers. In the event he offered the DA just six ministries. This represented just 18.75% of the cabinet posts, despite the party holding 30.3% of the government of national unity’s 287 seats in parliament. In addition, the DA received six deputy ministerial positions, of which only two are the sole deputy post in their respective departments.

South Africa’s challenges

South Africa lurching from crisis to crisis

For both the key actors in government this alliance has been difficult to swallow. There has been widespread praise for the pragmatism of the ANC leadership in negotiating a government of national unity in international media; and, hardly surprisingly, the South African stock market has bounced and the value of the rand has rallied. Other media voices are much more cautious. Like the 1994-1997 government of national unity, this latest experiment of coalition government includes radically different ideological bedfellows and it may yet unravel. As Jonny Steinberg, (based at Yale’s Council on African Studies) has underlined, many ANC officials would find it hard to work with the DA, which they regarded as “the local chapter” of international forces trying to push South African politics towards the right.

Three important aspects of the new GNU have not received much attention in the press. Firstly, how will decision making process be managed in the sprawling, and greatly-expanded Cabinet? Professor Stephen Chan has made the very important point about the clearing house mechanisms if it is to function effectively. Before the 2024 election result, power and decision making rested in the African National Congress and the ANC hierarchy, i.e., the core group of advisers around the President. In all, the key people within the ANC comprise approximately 100 people – the elected 80-members of the ANC’s National Executive Committee which includes the top 6 politicians, plus a few coopted members. Historically, the NEC has been the leading decision-making body; indeed, it has recalled two sitting presidents in the past. However, over the past twenty years power and decision-making progressively shifted elsewhere. Dating back to the era before Jacob Zuma’s arrival in office in 2009, the ANC’s deployment committee based at Luthuli House in Johannesburg played a decisive role in the pattern of appointments to key positions in parastatals and the civil service. In classic Stalinist style, this was how Zuma ensured key political allies and pliant acolytes were put in place across the South African state at national and local level. This committee’s role in cadre deployment played a crucial part in accelerating ‘state capture’, documented in meticulous detail by the Zondo Commission report and revealed by Daily Maverick journalism.

The inauguration of the GNU threatens this ANC’s pattern of appointments and preferment. While in opposition, the Democratic Alliance made getting rid of this political appointment process as one of the top items on their agenda. On the other hand, there are acute concerns that DA ministers could be “held hostage” by existing senior civil servants, who had been “deployed” by the ANC as party cadres, and whose loyalties lay with the party rather than their duties to wider society. As the analyst Gareth van Onselen argued, DA ministers could be in an invidious position.

The ANC has been in command of the national government for three decades, during which time it has pursued a policy of appointing party loyalists to positions in the state, from top to bottom. This was done surreptitiously at first but in October 1998 the liberation movement openly declared its intention of seizing control of all “levers of power” in the state and elsewhere.

The DA and the smaller parties in the GNU are all hyper-aware of the danger of being weak partners in a coalition, propping up the ANC which still gained 40% of the national vote, and being tarred in the eyes of voters with any mistakes forced on them by a government in which they have limited influence.

There are also other competing political players which have been relatively ignored in the press coverage around the election: the role and influence of domestic and foreign business, and trade unions. How will these competing constituencies influence the GNU? The key interface between business and the country’s political leadership, and consequent decision making, doesn’t get mainstream coverage it deserves. Yet South Africa has had a corporatist political culture since the days of apartheid. In the years following the unbanning of the ANC and the transition to black majority rule, ‘big business’ made a highly deliberate play to coopt leading ANC figures to protect their interests.[Pieter du Toit, The ANC Billionaires. Big Capital’s Gambit and the Rise of the Few].

Thirdly, what does the GNU presage for South Africa’s foreign policy? ‘ Will there be a shift to the West? Or against the West?’ Since 1994, the ANC has consistently emphasised regional, continental and Global South interests. Non-alignment has also featured prominently; this has meant an openness to ties and collaboration with Russia and China, to the alarm and anger of their Western critics and opponents. Similarly, the ANC’s unequivocal support for the Palestinian cause has deep roots, dating back to the struggle against apartheid and a sense of solidarity against what was regarded as imperialist oppression, strengthened by the close geo-strategic links between the apartheid government and Israel. South Africa’s role in bringing Israel’s prosecution of the war in Gaza before the International Court of Justice has been a source of considerable pride for many South Africans. ANC continued active support for Palestine will be difficult for the DA’s minority of Jewish voters, who identify closely with the Israeli cause. In John Matisonn’s view, “While there are ministers in the new government eager for change, the country’s system is likely to maintain the status quo.”

Will this national coalition government hold? This depends on the good faith of all parties, and whether the balance of interests favours governance, delivery and repair of critical infrastructure rather than radical policies which risk alienating business and foreign investment. If the South African economy is to return to desperately needed growth, there is a need for political stability. If South Africa’s leading politicians can achieve stability at national level, perhaps – just perhaps – this will actively foster and encourage more effective coalitions at provincial and metro level. The omens, however, are not good. In Gauteng, the heart of the country’s economy, the ANC took such a hard-line stance, excluding the DA from all but a handful of seats, that the DA walked away from the deal. Tensions remain high and there is no guarantee that the Government of National Unity will last. Analysts have argued that grassroots pressure for better government at municipal level offers the best hope for South Africa’s future. Leading by example from the top would be a very good thing too.

Martin Plaut is a Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies and Sue Onslow is Visiting Professor at the Department of Political Economy, King’s College London.

Related articles:

The Round Table appoints a new editor

The Briefing Room – South African and India elections: the aftermath