Oversight Group report cover and recommendations from the Church of England website.

Oversight Group report cover and recommendations from the Church of England website.

[This is an excerpt from an article in The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs. Views expressed do not reflect the position of the editorial board.]

Since the controversial killing by the police in the United States of several people of Afro-American heritage, there have been increasing demands for penitence and reparative justice for the wrongs inflicted on slaves and their descendants.

The churches too have been found to have benefitted from the trusts and charities established by those engaged in the slave trade or those profiting from chattel slavery. There have been calls for the churches to express repentance for such involvement and to set up funds to compensate the descendants of slaves for the wrong done to their ancestors.

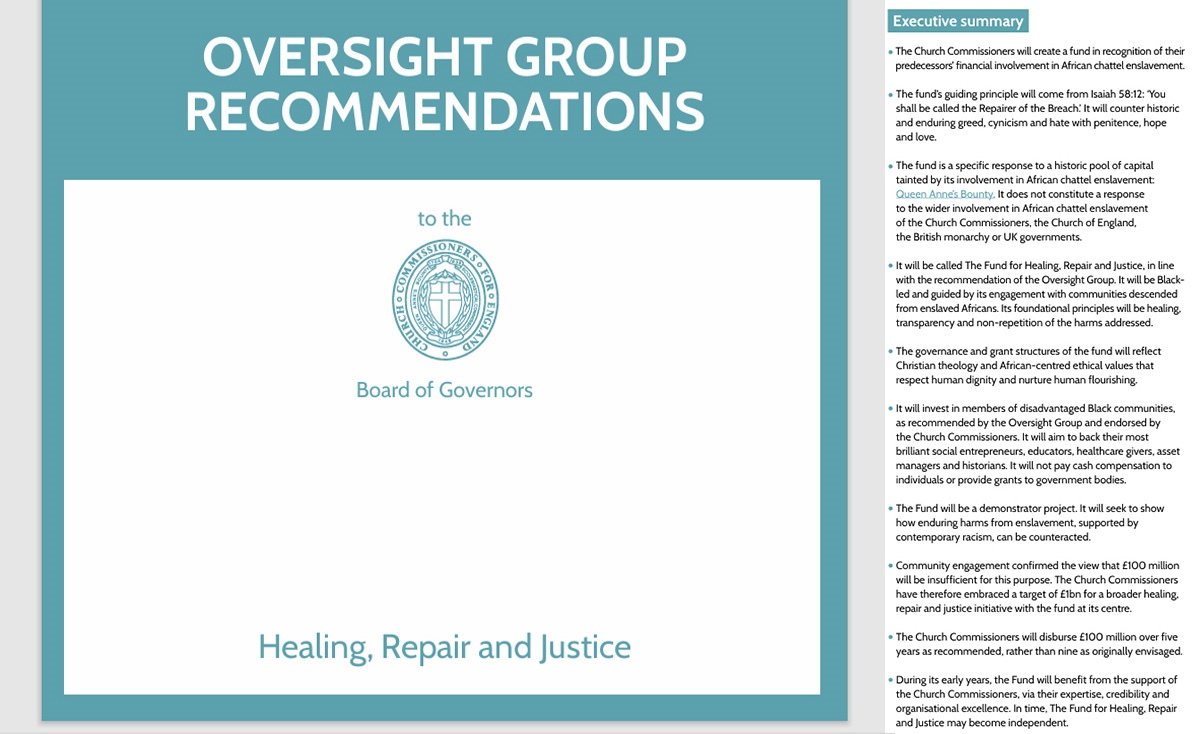

The Church of England’s Oversight Group has gone further than that and has issued a call for the Church to apologise for mission by its agencies to Africa, for denying that Africans too have been made in God’s image and for destroying African traditional belief systems (see, https://www.churchofengland.org/media/press-releases/church-commissioners-england-warmly-welcomes-oversight-groups-report). We need to ask, at once, whether these allegations are true and, if so, what should be done about them?

Oversight Group Report

Research Article – An African Union-Caribbean Community alliance in the global reparations movement: promises, perils, and pitfalls

Sorry is not the hardest word – reparations is

Reparations for Slavery Becomes A Commonwealth Issue

We need to note, first of all, that chattel slavery has been universal and can be found in the histories of every people, continent and nation. Philosophers like Aristotle argued that the state of slavery was ‘natural’ for certain kinds of people. All the empires of antiquity had slavery of prisoners of war and of commercial acquisition embedded in them. Many of these slaves were routinely sold in the markets of the Roman Empire. Some Ottoman rulers and the notorious Barbary ‘pirates’ enslaved large numbers of Western Europeans for slavery in North Africa until the 18th century.

Historians and social scientists have shown how slavery was, at first, ameliorated and then disappeared with the advance of Christianity in Western Europe. From the time of Constantine, it cannot be denied that Christianity was a major influence in the fading away of slavery.

It is true that the Bible was sometimes used, especially in the ‘Deep South’ of the United States, to justify slavery but it is equally the case that the Bible was increasingly used by Evangelicals, from the mid-eighteenth century onwards, to oppose the slave trade and slavery itself on the grounds that all human beings had been created in God’s image. The ending of the slave trade and then of slavery itself was largely due to the unflagging zeal of Evangelical campaigns that gripped the imagination of the population at large. The Oversight Group seems not to have known that after the abolition of the trade, the Royal Navy was assiduous in intercepting slave ships off the coast of West Africa and setting the slaves free. Church agencies, like the Church Missionary Society, were engaged in the resettling of these freed slaves.

In East Africa, similarly, after David Livingstone’s call for ‘Christianity and commerce’ rather than the slave trade, missionaries attempted to penetrate the interior by following the routes of the Arab slave and commodity traders. I wonder whether the Oversight Group canvassed the views of the large Anglican churches in countries like Kenya, Uganda and Nigeria for their views about apologising for the mission which brought them their faith and which brought education and modern medicine to their people, whilst also challenging many of the social evils of their societies. Many paid a high price for their witness against tyranny and corruption.

Mistakes were made, of course, regarding culture, custom and family life but the effects of those mistakes are been being addressed by the African churches themselves. Eminent European and African scholars like John V Taylor, John Mbiti and Kwame Bediako have been engaging with the best of African spiritualities and have noted both continuities and discontinuities with it in the Christian churches. The credibility of the Oversight Group would have been immeasurably enhanced if the leadership of the African churches had been represented in its membership.

The question of ‘reparations’ is a knotty one: how should they be paid? To whom? What counts as ‘reparation’? There are so many claimants. Not only the descendants of chattel slaves but also the families and communities disrupted in Africa and elsewhere by chattel slavery. People in other parts of what was the British Empire may have their own grievances of denudation of their land by colonists, the exploitation of the poor and of commodities like spices, cotton, minerals etc. Should they also be paid reparations? What about the working classes in the U.K. who were also exploited in the cause of the Industrial Revolution and where men, women and children faced the most atrocious working conditions, denied basic hygiene, leisure and education? Should there be reparations for them also?

Michael Nazir-Ali is the former Bishop of Rochester, Catholic Prelate, and a member of the Round Table Editorial Board.

Related articles:

Former Jamaican Prime Minister welcomes reparations on the agenda of the next CHOGM

Prince Charles expresses sorrow over slavery in Commonwealth speech