[This excerpt is from an article in The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs.]

The reader of this book is torn between being tremendously impressed by the phenomenal range of scholarship that has gone into it and a sense of being oppressed by the inexorability of its detail. Then there is the title. Could it be about the literature, fictional and poetic, relating to the empire? After all, the author is a literary scholar. What about approaches to the history of empire? But it is about neither of these. It is essentially based upon enormous caches of letters, diaries, as well as articles and books, some of them unpublished, left by the various branches of the McIlwraith family of Ayrshire, Scotland. Like so many Scottish families, several of their members headed for the empire in the later 19th century, making careers there, and creating their own diasporic families, yet often retaining connections with the culture of their origins. Many of Kröller’s sources illustrate (p. 68) ‘how punctilious communication, both in writing and in person, sustained the immigrant community, enriched business, and facilitated scientific exchange’. The author is equally punctilious in her extensive survey of these communications and a short review like this can only provide a taste of the complex by-ways of the work.

The book is essentially divided into two geographical areas, Queensland in Australia and Ontario in Canada. The most celebrated, or notorious, of the McIlwraiths, was Sir Thomas (1835–1900), who followed his brother to Victoria, Australia. Eventually moving to a remote pastoral station in Queensland, he later settled in Brisbane. There he entered Queensland politics in 1868 and became premier in 1879. He was always a controversial figure, brash, dominant and impatient with opposition. But for the imperial government, he overstepped the mark in 1883, when fearful of German encroachment in the Pacific, he resolved to annex New Guinea to Queensland. McIlwraith has received a great deal of attention from historians, but Kröller examines family papers to reveal his relationships with the wider family, the nature of his marriage, perceptions of him by contemporaries, and above all the reactions of London when he decided to develop his own imperialism. His attitudes towards and treatment of both Aboriginal peoples and indigenous Pacific islanders, pulled into labour migration to Queensland sugar plantations, was representative of the period’s racism and social Darwinian predictions of decline and extinction. Never in good health, he was eventually forced out of politics.

Commonwealth Bookshelf

Book Review: The Enduring Crown Commonwealth – The Past, Present and Future of the UK-Canada-ANZ Alliance and Why it Matters

While it is true that there were many members of the Australian branch of the McIlwraiths with other careers, the migrants to Ontario seem rather more appealing. Another Thomas (1824–1903), from a different branch and demonstrating Scottish families’ adherence to specific naming practices, migrated to Ontario in 1853. He became a businessman in Hamilton, but more particularly an ‘amateur’ ornithologist not least through the publication of his book The Birds of Ontario and his connections with other North American ornithologists, including many in the United States. After an examination of a Family Album, to which several members of the Ontario McIlwraith family made contributions, Kröller follows up the career of one of Thomas’s daughters, Jean, who worked in publishing (while also being a creative writer herself) in New York. Her writings, both published and unpublished, are analysed in some detail by Kröller, The book then takes a slightly disorientating and awkward turn in a chapter in which the American-born (with a Scottish grandfather) Beulah Knox spends time at a language school in Dresden and then extensively tours Europe on the eve of the First World War, corresponding copiously as she does so. There is much in this that unveils the lives of elite girls and their linguistic ambitions as part of their ‘finishing’ as cultivated society members supposedly on the look-out for good marriages, but all becomes clear when we find that Beulah marries yet another Thomas McIlwraith (1899–1964), whose life and immense correspondence are analysed in the final three chapters of the book. This Thomas, brought up in Hamilton, Ontario, was a passionate imperialist who eagerly set out to do his patriotic duty in the First World War. Joining the Scottish regiment, the King’s Own Scottish Borderers, he crossed the Atlantic for training. While missing the action of the war, he was a member of the army of occupation that entered Germany. Highly literate, throughout this epochal period, he sent a stream of letters about his experiences to his family. He then became an ex-serviceman entrant to Cambridge University and studied anthropology, encountering both some of the pioneering anthropologists of the age and the eccentricities (and misogyny) of the university. His field work was in Bella Coola in northern British Columbia, among the Nuxalk people, and after toying with the prospect of work in the colonial service, he succeeded in securing a post at the University of Toronto.

John M. MacKenzie, University of Edinburgh.

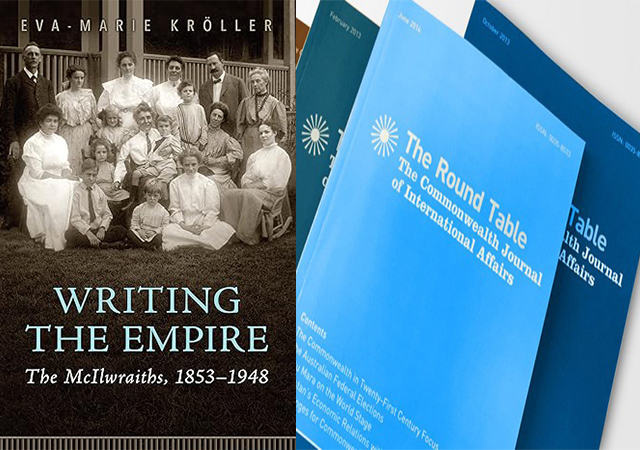

Writing the empire: the McIlwraiths 1853–1948 by Eve-Marie Kröller, Toronto, Toronto University Press, 2021.