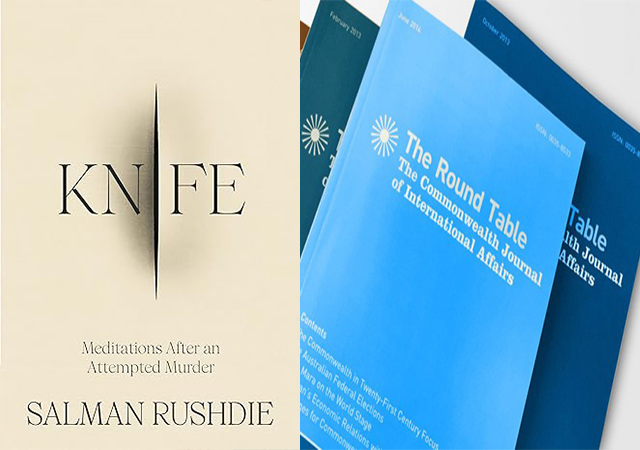

[This is an excerpt from an article from The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs.]

It would require a heart of stone not to sympathise with Salman Rushdie over the horrific injuries he sustained at the hands of an assassin on 12 August 2022 while preparing to give a talk in upstate New York that summer morning (the talk, poignantly, was to have been on the importance of keeping writers safe from harm). Now, nearly two years on, Rushdie has brought himself to describing that attack and its aftermath in excruciating detail in this gripping memoir which also contains his reflections on a number of other matters (unsurprisingly, he has dedicated the book to ‘the men and women who saved my life’, of which there were many).

Of the attack itself, he recalls it simply thus:

I can still see the moment in slow motion. My eyes follow the running man as he leaps out of the audience and approaches me. I see each step of his headlong run. I watch myself coming to my feet and turning toward him. (I continue to face him. I never turn my back on him. There are no injuries on my back.) I raise my left hand in self-defense. He plunges the knife into it.

After that there are many blows, to my neck, to my chest, to my eye, everywhere. I feel my legs give way, and I fall. (pp. 3–4)

What follows has drama, pathos, horror, upheaval, pain and much else, all brought to the printed page with the consummate story-telling skills that Rushdie is justly famous for. He is emphatic – and this may surprise many readers – that, in his view, ‘whatever the attack was about, it wasn’t about The Satanic Verses’. (p. 5]) He refuses to name his assassin, calling him just ‘the A’ throughout the book (in real life, the perpetrator of this heinous crime is Hadi Matar, a 24-year-old man from New Jersey, born to immigrants from southern Lebanon, who has reportedly confessed to a dislike for Rushdie for his disobliging remarks about Islam). Rushdie does, however, want to ‘imagine my way into [Matar’s] head’ [p. 137] and towards this end, he constructs a long fictional conversation with his attacker, conducted over four sessions, which occupies some 30 pages of the book. That conversation ends with Rushdie declaiming:

There’s a thing I used to say back in the day, when catastrophe rained down upon The Satanic Verses and its author: that one way of understanding the argument over that book was that it was a quarrel between those with a sense of humour and those without one. I see you now, my failed murderer, hypocrite assassin, mon semblable, mon frère. You could try to kill because you didn’t know how to laugh. [emphasis in original, pp. 167–8]

The injuries and medical procedures endured by Rushdie and described in the book in graphic detail, are not for the faint-hearted. What the doctors had to do to his damaged eye, in particular, makes gruesome reading. ‘Let me’, says Rushdie with understated wryness, ‘offer this piece of advice to you, gentle reader: if you can avoid having your eyelid sewn shut … avoid it. It really, really hurts’. (p. 69) To add to his woes, he also faced a cancer scare within days of leaving hospital. ‘I was’, he reflects, ‘at a loss for words. Really? After I narrowly survived a murder attempt, now I had to face the prospect of cancer? This was unacceptable. It was unfair’. [emphasis in original, p. 113] In the event, that turned out to be a false scare.

More book reviews from The Round Table Journal

Commonwealth Bookshelf

Aside from ruminations about his physical state – which form the bulk of the book – there are passing references to Rushdie’s bitterness over the criticisms (‘widespread hostility’, as he calls it [p. 90]) that The Satanic Verses drew, immediately after its publication, from a number of prominent personages in the West, including the former US President Jimmy Carter, the feminist writer Germaine Greer and the historian Hugh Trevor-Roper.

Even more hurtful was the rejection by the people about whom I had written – had done so with, I thought, love. I could come to terms with the attack from Iran. It was a brutal regime, and I had nothing to do with it, expect that it was trying to kill me. The hostility emanating from India and Pakistan and from South Asian communities in the United Kingdom was much harder to bear. That wound remains unhealed to this day. I have to accept that rejection, but it’s hard. (p. 90–91)

He says that he took some consolation from publicly embarking on a defence of free speech principles – which, of course, he did and for which he was rightly commended (even after recovering from the knife attack, he has spoken out against censorship and the cancel culture, including from the left, and has excoriated the ‘offence industry’ in the modern media landscape – see, e.g., his interview to the CBS television channel in April 2024).

Rushdie offers an interesting analysis of the state of freedom in present times. Freedom, he avers, is a word that has become a minefield:

Ever since conservatives started laying claim to it (Freedom Tower, freedom fries), liberals and progressives had started backing away from it toward new definitions of the social good according to which people would no longer be entitled to dispute the new norms. Protecting the rights and sensibilities of groups perceived as vulnerable would take precedence over freedom of speech … This move away from First Amendment principles allowed that venerable piece of the Constitution to be co-opted by the right … It became a kind of freedom for bigotry … All of this, and my desire to protect the idea of freedom – Thomas Paine’s idea, the Enlightenment idea, John Stuart Mill’s idea – from these new things, was beyond my power to articulate. (p. 62)

Venkat Iyer is the Editor of The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs.

Knife: Meditations after an attempted murder by Salman Rushdie, London, Jonathan Cape, 2024.