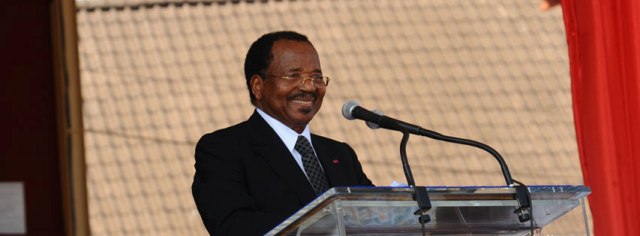

The Cameroon's Constitutional Council declared that Biya had secured 90% of the vote in some areas [photo: Facebook page].

The Cameroon's Constitutional Council declared that Biya had secured 90% of the vote in some areas [photo: Facebook page].

After six consecutive terms in office, dating back 36 years (longer than two-thirds of Cameroonians have been alive), the re-election of Paul Biya, 85, to the presidency in October surprised few observers of the west African country, still less the electorate. A Washington Post analysis before the polls was headlined: ‘Cameroon has an election Sunday – and everyone already knows the winner.’

It was nevertheless surprising to see the president of neighbouring Guinea Bissau, Teodoro Obiang (Biya’s closest rival for longevity in office, having been in power since 1979) congratulate his fellow octogenarian ruler on his election win two days before the results were announced, as the BBC reported. Cameroon state television duly tweeted on 22 October that Biya had won re-election with 71% of the vote on a turnout of 54%, with Maurice Kamto of the Cameroon Renaissance Movement (MRC/CRM), credited with just 14.2%, according to Reuters. Kamto claimed victory anyway and called for a peaceful transfer of power.

The 85-year-old Biya certainly displayed an insouciant confidence. An investigation by the multinational Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project reported that the president ‘rules from afar’, spending up to a third of the year in the luxury InterContinental hotel in Geneva, at a cost of $65m so far. The BBC reported that Biya only held his first cabinet meeting for two years in March, while Kamto claimed Biya had campaigned for just seven minutes.

The Constitutional Council declared that Biya had secured 90% of the vote in some areas, and won strongly in nine of the 10 regions. It also dismissed 18 petitions protesting against electoral irregularities filed by the opposition. However, the International Crisis Group (ICG) reported fatal violence during polling in the increasingly secessionist anglophone regions and noted that this was the first time that the opposition had unanimously rejected the results of the elections. Reuters said overall turnout was a low 54% with just 5% in the north-west and 16% in the south-west, both anglophone strongholds. By a strange coincidence, two days after the council declared the win for Biya, tenders were announced for building a $500,000 mansion for the president of the council, Judge Clement Atangana, whose wife is an MP for the ruling party. The BBC said many Cameroonians regarded this as payback for his loyal service to Biya.

Security forces locked down Yaoundé, the capital, and Douala, the economic centre, ahead of the results being declared, the Guardian reported. As Biya’s security forces suppressed street protests against the results, Voice of America reported that demonstrators had taken their demonstrations to safer ground, such as the university and the cathedral in Yaoundé. The MRC/CRM criticised Biya for sending soldiers to attack innocent people protesting for their rights, though he had failed in the wars declared against the Islamist insurgents of Boko Haram and the anglophone separatists. The Committee to Protect Journalists said a prominent critic, Michel Biem Tong, editor of the Hurinews website, had been detained on unknown charges. The South Africa-based Centre for African Journalists reported that the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative and 27 other civil society organisations had urged the Commonwealth to suspend Cameroon ahead of the Commonwealth Ministerial Action Group meeting on 28 September. In July, Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, head of the United Nations’ human rights body, the OHCHR, expressed alarm at reports of human rights abuses and, after a video emerged of Cameroon soldiers apparently executing four women and children accused of belonging to Boko Haram, criticised the refusal of the Biya government to allow the UN Human Rights Office access. The Guardian reported about families sleeping in the jungle to escape the conflict. With separatists enforcing a boycott of schools across the two anglophone regions and an estimated 75,000 people internally displaced and up to 50,000 refugees fleeing over the Nigerian border, according to Human Rights Watch, tens of thousands of children have been prevented from attending classes since 2016. The Guardian reported in July that Cameroon armed forces had set fire to 20 villages, with at least four people burned alive. In early November 79 children and three staff were abducted from a school in Bamenda, northwest Cameroon, days after another kidnapping at the same school, the BBC reported. The children were released after a few days after each incident. The government and the separatists accused each other of being behind the kidnapping.

Biya’s heavy-handed crackdown on initially peaceful attempts to secure political reforms, greater civil rights and autonomy for the anglophone regions in 2016, led by teachers and lawyers, had fuelled the rise of the armed struggle, Paul Melly, of the Chatham House thinktank, told the BBC. Another analyst, Nna-Emeka Okereke, said militias that had sprung up in the past year, with names such as Red Dragons, the Seven Karta, the Tigers and the Ambazonia Defence Forces (ADF), had made the north-west and south-west ‘ungovernable’, despite being vastly outnumbered and outgunned by the US-trained Cameroon army. ‘They probably have 500 to 1,000 active fighters, but more importantly they have the morale and determination to fight for the independence of what they call Ambazonia state.’ There had been 83 armed clashes with government forces this year, with 295 deaths, compared with just 13 encounters last year and 39 deaths, according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project.

The violence is continuing to worsen – a security official was beheaded by separatists in October, the CJA said, while Reuters reported heavy fighting between armed forces and rebels that killed at least 10 people later in the month. John Fru Ndi, veteran leader of the opposition Social Democratic Front, whose home was burned down by suspected separatists, condemned militants who threatened villagers they were supposed to be fighting for and said the various Amabazonia factions should re-examine their strategies after hijacking the struggle, Journal du Cameroon reported.

The ICG backed plans by a coalition of Christian and Muslim leaders to convene a Anglophone General Conference, urging the government to release detainees and guarantee free passage to activists in exile, and to start a dialogue with the separatists. ‘Blocking the conference, repressing separatists and incarcerating more moderate anglophones risks preparing the ground for a devastating civil war that would threaten the entire country’s stability and the government’s own survival,’ the ICG said.