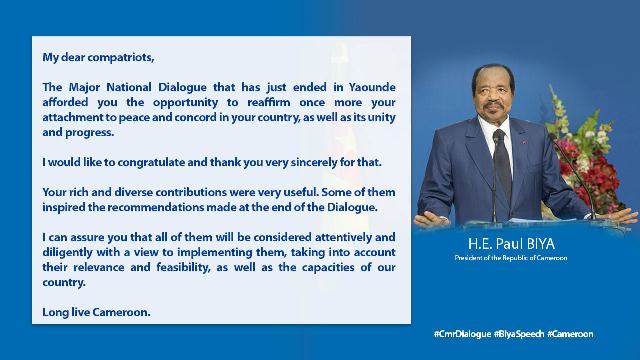

President Paul Biya held a National Dialogue in 2019 to try and heal rifts. [photo: President's Facebook page]

President Paul Biya held a National Dialogue in 2019 to try and heal rifts. [photo: President's Facebook page]

As the anglophone crisis enters its fourth year, after an estimated 3,000 deaths and 500,000 people displaced in the north-west and south-west regions, hopes of a breakthrough in the conflict were dashed by renewed threats from Paul Biya, Cameroon’s 86-year-old president, over the new year after his apparent overtures to the separatists at a ‘National Dialogue’ in September-October and at the Paris Peace Forum in November.

The UN Children’s Fund warned that the violence now threatened 1.9 million people – a 15-fold increase – with nearly a million of them children. Attacks by Cameroon’s military and separatists – who also target the moderate opposition Social Democratic Front (SDF) – as well as by Boko Haram, are increasing. Civilians have attacked separatists in retaliation for atrocities against them. Torture at secret detention facilities by Cameroon’s armed forces, documented by Human Rights Watch last year, continues unabated.

Another element to the volatile mix emerged in late October as Facebook said it had suspended accounts linked to networks run by the notorious Russian ‘troll factory’ run by Yevgeny Prigozhin, a powerful tycoon close to Vladimir Putin. Prigozhin was trying to influence domestic politics in eight African countries, including Cameroon, Facebook said.

Instead of promising new peace efforts in his end-of-year message, as hoped for, Biya threatened to crush separatist fighters, saying the military would act ‘without weakness’. The SDF leader, John Fru Ndi, said Cameroonians had expected Biya to free the separatist leader Ayuk Tabe Julius and nine others sentenced to life in prison for ‘terrorism and secession’ in August. ‘I expected that in a speech like this he would say, “Anglophone activists, I pardon you … But Mr Biya said, “If you want peace, be prepared for war.”’

Maurice Kamto, leader of the opposition Cameroon Renaissance Movement (MRC), called for dialogue and said Biya was deceiving himself and the world that he was resolving the crisis. Kamto, the nearest challenger when Biya won 2018’s disputed elections to extend his 36 years in power with a seventh term, was freed in October after being detained for nine months for organising protests.

As well as proposing more autonomy for the anglophone regions and reviving the House of Chiefs (which lasted from independence in 1960 to 1972, when Cameroon’s federalism was dropped and anglophone regions annexed) in the National Dialogue, Biya freed more than 300 detainees, though critics said thousands more remained jailed on bogus charges. Separatists refused to attend unless all political prisoners were released and the military withdrew from anglophone regions. ‘We want independence and nothing else,’ said Ivo Tapang, a spokesman for 13 armed groups called the Contender Forces of Ambazonia.

On 20 December, Cameroon’s parliament granted ‘special status’ to the anglophone regions based on their ‘linguistic particularity and historic heritage’. Schools and courts were cited in the legislation, reflecting the role of teachers and lawyers in leading protests that sparked the secessionist movement in 2016 (see Commonwealth Update, March 2018). But Jean-Michel Nintcheu, an SDF MP, said the law would not solve the crisis. ‘The anglophones, even the moderate ones, want a federal state. This law is not the result of a dialogue … we were against it,’ he said.

In November the US imposed trade sanctions after cutting military aid in February. An open letter at the Paris Peace Forum’s launch urged the French president, Emmanuel Macron, to take a stronger stance on the Cameroon crisis. One signatory, Rebecca Tinsley of Waging Peace, linked the reluctance of the west to intervene to Cameroon’s role in fighting Boko Haram. ‘It’s a case of the Cameroonian armed forces being a militia for hire,’ she said. ‘[Cameroon] has sort of inoculated itself against criticism.’ A well-intentioned tripartite mission by the head of the African Union Commission, Moussa Faki Mahamat; Patricia Scotland, of the Commonwealth; and Louise Mushikiwabo, secretary-general of the International Organisation of La Francophonie; urged all parties to follow ‘the path of wisdom and responsibility’ but appeared to have little effect.

Legislative and municipal elections are due in February but it seems unlikely there will be a high enough turnout to give the polls credibility and attacks by separatists seem highly likely. Candidates have been abducted by separatists and the Ambazonia Military Forces declared a curfew during the elections.

Writing in African Arguments, R Maxwell Bone and Akem Kelvin Nkwain note that ‘few outside of the ruling CPDM party regarded [the National Dialogue] as a genuine effort to end the conflict.’ All secessionists and much of civil society boycotted the talks, while those opposition politicians that did attend soon walked out. Bone and Nkwain point out that Biya will still appoint governors, who are likely to still be francophone, as well as district officers. Forming committees to discuss decentralisation and local finance was ‘an approach that has led to little change over several years’. Regional assemblies, executive councils and mayors will have as-yet undetermined powers and ‘their responsibilities will largely be determined by laws implemented in Yaoundé.’

Bone and Nkwain conclude: ‘In all likelihood, this means that the two sides will continue to fight whilst wreaking havoc on civilians in the two anglophone regions. The special status bill will do little to change this.’ Biya’s moves to pacify the separatists appear to be too little, too late.