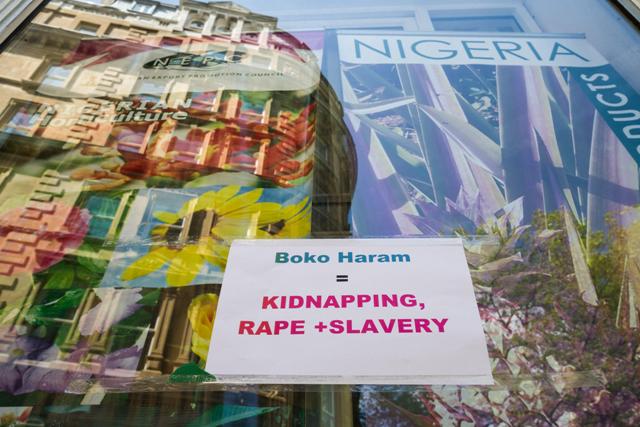

London, 3rd May 2014. Protest signs against Boko Haram outside the Nigerian Embassy in London [Credit: Guy Corbishley/Alamy Live News]

London, 3rd May 2014. Protest signs against Boko Haram outside the Nigerian Embassy in London [Credit: Guy Corbishley/Alamy Live News]

[This is an excerpt from a research article which appeared in The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs.]

One major factor that has led to spread of radical Islamic ideologies is the advancement of technology. The internet and social media have facilitated the growth of radicalisation amongst Nigeria’s Muslims and especially youth. As a trained Salafist and great admirer of the fourteenth-century jihadist ideologue, Ibn Taymiyyah, Mohammed Yusuf nurtured his followers with this doctrine until his death in 2009. Though he was killed, his message has outlived him and has become viral within the North-Eastern region. The Nigerian government was not fully aware of this movement.

This is surprising given that the sole aim of the group is to convert Nigeria and Nigerians into a Muslim Wahhabist state and Muslim Wahhabists respectively and the fact that it recruits from the Ibn Taymiyyah network of schools which Yusuf had created. This is due, in part, to the lack of success of the state’s intelligence apparatus in penetrating Boko Haram. These ties of allegiance between disciples and religious clerics are extremely difficult to break. Also, the government has failed to recognise the potential assets that extremist groups readily have at their disposal. The existence of armed gangs in the northern region of Nigeria is a vivid example. These groups include, but are not limited to, the Almajirai, Van Tauri, Van Daba, Van Banga and Van Dauka Amariya and they readily serve as a recruitment ground for extremist groups.

Furthermore, the counter-terrorism drive by the government is crippled by the inability of the Nigerian Police Force to gather intelligence and carry out forensic investigations . According to Amnesty International, ‘most police stations do not document their work, there is no database for fingerprints, no systematic forensic investigation methodology, only two forensic laboratory facilities, few trained forensic staff and insufficient budgets for investigations’. As a result, the police tend to rely solely on confessions made and most often extracted from suspects under duress, which form 60% of all prosecutions. In many instances, the guilty often escape while the innocent suffer. In terrorism cases, despite the large number of arrests of alleged Boko Haram members and sympathisers, very few have been followed through to a reasonable conclusion. Corruption within the rank and file of the Nigerian Police Force continues to undermine the counter-terrorism initiatives.

In addition, while military action taken by the Nigerian government is deemed necessary in its counter-terrorism effort, apprehensions have been raised over the modus operandi of its engagement and the general conduct of troops in the theatre of operations which is far from the standard rules of engagement. Counter-terrorism efforts are therefore proving unproductive due to the brutality unleashed by the security forces on the wrong targets. The Joint Task Force (JTF) in the North-Eastern region, engages in unlawful killings, arrests, extortion and intimidation of residents of the region as noted in the preceding section.

Evidence has shown that rather than carry out intelligence-driven operations, the JTF engages in random house-to-house searches, and at times shoots young men found in these homes. These were the tactics used by the JTF in the Kaleri Ngomari Custain area in Maiduguri on 9 July 2011, where 25 people were shot dead in their homes by officers of the JTF, women and children were molested, homes were burnt, and many men and boys were reported missing. Such outrages on the part of the JTF can only reduce the popularity of the government’s drive against terrorism as security services meant to protect civilian lives and properties enter homes to kill husbands and sons and molest women and girls.

This situation is further worsened by the fact that officers who make up the JTF are not local to the regions where they operate and are not familiar with the culture and terrain of those localities; as such the inhabitants see themselves as under the siege of a foreign security force. This has made people lose trust in the counter-terrorism efforts of the government because of the wide gap that exists between the promises made and performance witnessed. While promises have been made to end the scourge of Boko Haram, the actions of government do not reflect a sense of commitment to this ambition.

Samuel K. Okunade is a Post-Doctoral Fellow, Centre for Advancement of Scholarship, University of Pretoria , South Africa and Olusola Ogunnubi is a Research Fellow, Centre for Gender and African Studies, University of the Free State , South Africa.