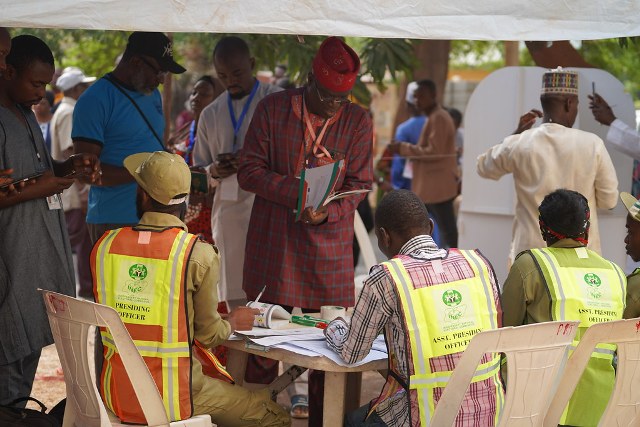

Voting in Nigeria's 2023 elections [source: Commonwealth Secretariat Flikr]

Voting in Nigeria's 2023 elections [source: Commonwealth Secretariat Flikr]

[This is an excerpt from an article in The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs.]

Wealth and party switching

Politics is expensive in both developed and developing democracies alike, and to run a viable political campaign, politicians need to have strong financial backing. While donations could be sought from the private sector to support political campaigns, Arriola et al. (Citation2021) argue that African politicians seldom have this recourse to raise funds; rather, they are expected to expend their own money and other resources for political support. Nigerian politics is no exception to this, since both the public and party executives expect those vying for political offices to possess deep pockets for campaign expenses and handouts (Arriola et al., Citation2021; Lindberg, Citation2012). In Nigeria, it is obvious that politics is predominantly for the rich, given that the cost of party nomination forms is over a hundred times the country’s monthly minimum wage. The expression of interest and nomination forms alone (not adding other expenses) for the PDP for the 2023 election was about 3.5 million naira (Punch News, Citation2022), compared to the thirty thousand naira monthly minimum wage. As discussed by Agboga (Citation2023) on the ease of switching, wealth reduces the barriers to switching parties since party executives themselves actively encourage rich politicians to switch into their party to fund party expenses while advancing their own political ambitions. Koter (Citation2017, p. 576) argues that as campaign costs in Africa increase, including both traditional costs ‘such as printing posters and flyers and organizing meetings’, but also ‘transportation to rallies for their supporters, as well as food, drink, and entertainment’, less talented but wealthier politicians who can foot the bills crowd out talented but less wealthy candidates. With this, African democracies run the risk of replacing good leaders with simply wealthier ones with questionable character.

Nonetheless, many scholars of African politics have uncovered that wealth does not guarantee electoral success (Cheeseman et al., Citation2021; Lindberg, Citation2012). Cheeseman et al. (Citation2021) argued that while handouts from wealthy politicians could drive positives such as voter turnout and participation, wealthy candidates without credibility or a convincing story to tell behind the gifts they dole out often do not succeed at the polls. So, the moral justifications and promises made while giving out patronage and voters’ assessment of these is crucial. Relatedly, Lindberg (Citation2012) in his appropriately titled paper ‘Have the cake and eat it … ’ argued that, while African voters expect and collect gifts from politicians, the majority do not base their votes solely on the gifts received, but their general assessment of the candidates. Similarly, Gadjanova (Citation2020) argues that politicians give gifts to voters, voters expect gifts, but gifts do not guarantee victory. And since both incumbent and opposition compete in gift-giving, they adopt a second approach by constructing policy proposals for large group to outdo their opponents.

Opinion – Courts determining election winners instead of voters: A troubling development in Nigeria

Research Article – Digital technology and democracy in Nigeria: a study of how technology is transforming elections without necessarily deepening democracy

Opinion: Nigeria and the flawed 2023 elections

In Nigeria, when asked in the survey if they would choose a wealthy switcher over a non-switcher, a staggering 70% responded that they would choose a party loyalist, casting doubt on the power of wealth in shielding switchers from blowbacks of cross-carpeting. While they could be responding with the socially acceptable answer, Bratton (Citation2008) reveals that when voters were pressured by vote buying and electoral violence from both sides (incumbent and opposition) in Nigeria, they collected the money but stayed at home, or collected but secretly voted for their preferred candidates. So, there is corroborating evidence to suggest that money in and of itself has limited sway on Nigerian voters. However, it is important to admit the vital role of money in gaining political visibility, maintaining political networks, and even sponsoring community projects as Kramon (Citation2017) argues. So, while money could give politicians visibility, they need more than wealth to secure electoral victory as suggested in the survey response where only 30% responded that they were likely or somewhat likely to move camps with a wealthy party switcher.

Victor Agboga is a Doctoral Student, Department of Politics & International Studies (PAIS), University of Warwick, UK.