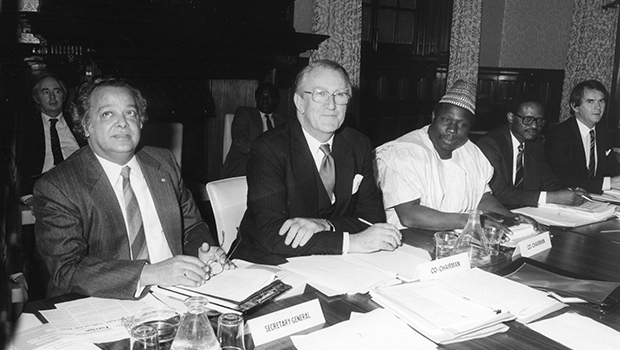

Eminent Persons Group Meeting in 1986: Shridath Ramphal, Malcolm Fraser, General Obasanjo, Chief Emeka Anyaoku, Hugh Craft (Photo: Commonwealth Secretariat archive)

Eminent Persons Group Meeting in 1986: Shridath Ramphal, Malcolm Fraser, General Obasanjo, Chief Emeka Anyaoku, Hugh Craft (Photo: Commonwealth Secretariat archive)

In the many years of his imprisonment, Mandela and his fellow prisoners had been a symbol of resistance and of hope. In that time, the Commonwealth had come of age, emerging from the skirts of the old imperial power, and establishing its own independent Secretariat and appointing its first principal officer, the Commonwealth Secretary-General. Racial and political equality now lay at the heart of the new Commonwealth and it was unsurprising that its predominant focus should be on Southern Africa, where these issues were at their most acute.

It was also predictable—if certainly wearisome—that the British government should feel conflicted between the demands of colonial freedom and national independence on the one hand and, on the other, what it saw as its strategic and commercial interest in the region and in apartheid South Africa in particular. Time and time again, whether on South Africa’s exclusion from the Commonwealth in 1961, Rhodesian Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) in 1965, the resumption of British arm sales to South Africa in 1971–74, the controversies over apartheid sport in the 1970s or the final stages leading to the birth of Zimbabwe in 1979–80, a distinctive and forceful Commonwealth approach was needed to hold the UK to international principles to which it was sometimes only tenuously committed.

By 1980, important changes were afoot. Within South Africa itself, it had taken the courage and determination of Soweto’s school students, in the 1976 revolt, to galvanise internal resistance. In the region, the Portuguese revolution, and the abandonment of its imperial territories in Africa, brought new allies to the frontline of African self-determination. The prolonged resistance war in Rhodesia, and the recognition that South Africa would no longer stand by its client state were the decisive factors in propelling the settler regime towards a settlement. As South Africa’s regional hegemony diminished, the violence on its frontiers intensified; and, as its economy faltered, internal protest and resistance increased.

Thatcher delivers to Botha on sanctions

By 1979, too, the UK had a new Prime Minister, and the first woman to hold that post, Margaret Thatcher. Despite her party’s manifesto commitment to recognise Rhodesia/Zimbabwe’s ‘internal settlement’, she was narrowly persuaded to refrain from doing so. Later in the year, meeting other Commonwealth leaders in Lusaka, she and her Foreign Secretary, Lord Carrington, embarked on a course which was to lead to the Lancaster House constitutional settlement and Zimbabwean independence, following elections, some months later.

Any thought that her enlightened actions on Zimbabwe would lead to new vigour to end apartheid in South Africa were to be quickly dashed. Throughout the decade of the 1980s, Mrs Thatcher conducted a campaign in the Commonwealth against the use of sanctions to end apartheid. It was not one in which any other Commonwealth country acquiesced; they all remained true to Commonwealth values, opposed her perverse evasion of them, and in the end prevailed in being among the forces that brought Nelson Mandela to freedom—and apartheid to its end.

The main encounters with Mrs Thatcher were at biennial Commonwealth Summit Meetings. In Melbourne, Australia, in 1981 and in New Delhi, the capital of India, in 1983, she effectively blocked a robust Commonwealth sanctions regime. At the Nassau Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in 1985, Mrs Thatcher was alone in seeking to protect South Africa from sanctions—as she proudly reported to President Botha within days of the Meeting’s end. The person who pointed a practical way forward was Prime Minister Bob Hawke of Australia. He wanted to complement the pressure of sanctions with the proposal that the Commonwealth should appoint a group of truly eminent persons to initiate and encourage the process of dialogue in South Africa.

I had, myself, become converted to the idea; but for the Commonwealth generally it involved a major strategic change from a policy of Pretoria’s isolation to one of dialogue; from talking to black South Africa in exile, to encounters with apartheid’s victims at home. It was a bold change after two decades of a policy of international isolation of Pretoria; but I felt that Hawke was right; that the time had come, while maintaining the pressure of sanctions, for the Commonwealth to confront apartheid in South Africa.

I recognised that many anti-apartheid activists would have misgivings about our shift to ‘dialogue with apartheid’. Trevor Huddleston told me that only his confidence in me prevented him from speaking out and that he might yet denounce it if his worst fears were fulfilled. For me, the key lay in the choice of the ‘eminent persons’ and I worked to secure a group of the highest quality. In the event, they turned out to be superlative in fulfilment of their mission. No one knew whether South Africa would cooperate; but the proposal had received Mrs Thatcher’s support and for Pretoria to reject it would put in jeopardy her protection of South Africa from further sanctions.

What is more, Mrs Thatcher agreed to a deadline of six months for a review of progress. Indeed, the Nassau Accord allowed for everyone going even further than the sanctions spelled out in the agreement if there continued to be no progress even beyond the six-month review, when: ‘each of us will pursue the objectives of this Accord in all the ways and through all appropriate fora open to us’. Altogether, it was a very strong message to Pretoria.

This is an excerpt from an article in a special edition of The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs on South Africa