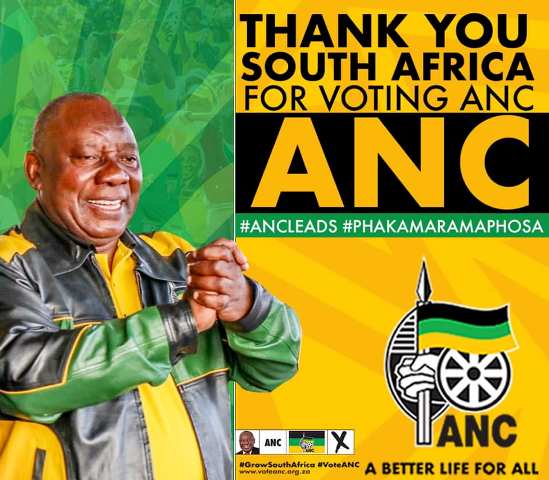

"Cyril Ramaphosa, president of South Africa and the ANC, was credited with saving the ruling party from humiliation". [Photo: ANC 'Thank you' on Facebook]

"Cyril Ramaphosa, president of South Africa and the ANC, was credited with saving the ruling party from humiliation". [Photo: ANC 'Thank you' on Facebook]

Corruption scandals, high unemployment and failing public services were widely blamed for the African National Congress’s worst election result since apartheid ended in 1994. Cyril Ramaphosa, president of South Africa and the ANC, was credited with saving the ruling party from humiliation.

Richard Calland, of the University of Cape Town, said Ramaphosa’s personal credibility had been pivotal. ‘He is the most trusted of the political leaders available to the electorate and more trusted … than his own party.’ But with more radical parties doing well, the election also reflected the polarisation of politics and swing from long-dominant parties seen elsewhere in recent years. The ANC won 230 of the 400 seats, 19 fewer than in 2014, while the Democratic Alliance (DA) was down five to 84. The DA will still be the main opposition party, with nearly twice as many seats as the third-placed Economic Freedom Fighters (EEF), which won 44. However, it was a disappointing result for the DA, which failed to increase its vote for the first time as it struggled to attract black voters while losing white support.

The left-wing populist EEF, founded by the firebrand former ANC Youth League leader Julius Malema, came out hugely strengthened, winning 19 seats on top of 25 won in 2014 and becoming the official opposition in three provinces. Inkatha, the party of the Zulu leader Mangosuthu Buthelezi, halted its steady decline from the 7% it won in 2004 to secure 14 seats. Vryheidsfront Plus (Freedom Front Plus), a populist party largely supported by Afrikaners and white farmers for its fight against land expropriation without compensation, was another big winner, more than doubling its tally to 10. Of the nine fringe parties with seats, the Congress of the People (Cope), which once hoped to challenge the ANC, appeared finished, with support dwindling from 7% in 2008 to under 1%. Another former hopeful, Agang, lost its two seats.

Though it still bestrides South African politics, the ANC’s share of the vote – just 57.5% on a 65.9% turnout – continues to steadily decline. In 1999 the ANC won 66% on an 89% turnout, and in 2004 the ANC under Thabo Mbeki got 69.7%. A decade later, under Jacob Zuma (who still faces multiple corruption charges), it was down to 62% (Update May 2014). Two years later, despite Zuma’s boast that the ANC would ‘rule till Jesus returns’, it lost control of Johannesburg and Pretoria after winning just 54% in local elections (Update Sept 2016). This year the ANC barely scraped 50% in the provincial legislature election for Gauteng, the wealthiest and most middle-class province, reflecting the erosion in support in the economic heartland (it won 68% there in 2004).

Fikile Mbalula, the ANC’s head of elections, said that if Ramaphosa had not beaten his rival for the leadership, Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, seen as a Zuma proxy, in 2017 then the ANC ‘would have probably dropped to 40%’. He suggested that many DA supporters had voted for the ANC because of Ramaphosa.

The president has a divided party behind him; the conference that elected Ramaphosa also put Ace Magashule, one of the old guard, in charge of the ANC as secretary-general. Robert Rotberg suggested in the Globe and Mail that Ramaphosa had been left hamstrung by his slim win when he needed a convincing victory to gain leverage over Zuma loyalists entrenched in the party and to draw a line between his government and the old order. ‘Ramaphosa will now have a tougher battle than his “good government” faction had anticipated against corrupt ANC ministers and officials,’ he said. But the Council for Foreign Relations disagreed: ‘The improvement in the ANC’s results over 2016 strengthens the hand of Cyril Ramaphosa.’

The president will certainly need his party behind him to tackle a long list of crises. According to the World Bank, South Africa is the world’s most unequal country by income: the top 1% own 70.9% of the wealth, while the bottom 60% share just 7%. The economy has not generated enough jobs for a population of 58 million, with a median age of 26 and almost a third under 15; the overall unemployment rate is 27.7% and 38% among the youth. Young voters shunned the election with many airing their disillusion under the Twitter hashtag #IWantToVoteBut. The education system is failing and ranked behind Zimbabwe, while the electricity rationing of the state power utility Eskom is pushing industries to move abroad. Amid corruption scandals and ‘state capture’, South Africa has fallen to 73rd of 180 countries in Transparency International’s corruption perceptions index so, above all, Ramaphosa must deliver on his promises to rid the ANC of ‘bad and deviant tendencies’.

If he fails, Rotberg suggested, ‘this may be South Africa’s last ANC government.’ However, for Natasha Marrian, writing in the Mail & Guardian, the ANC had been ‘allowed to rot and corrode’ and was ‘likely to miss the opportunity as its power-mongering factions regroup …Africa’s oldest liberation movement may just turn to dust.’

Related articles

South Africa’s election leaves the country stirred, not shaken