South African Social Attitudes Survey 2017–2018.

South African Social Attitudes Survey 2017–2018.

[This is an excerpt from an article appearing in the latest edition of The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs.]

Since the 1990s, academics have debated the causes of xenophobia in South Africa and how it spurs violence. We currently know a fair amount about how experts view the problem of xenophobic violence in the country. Most scholars disagree with the state-sanctioned ‘just crime’ discourse on anti-immigrant violence and a number of alternative explanations have been put forward provides a concise review of these alternatives). This study was the first to investigate what ordinary people think the main drivers of anti-immigrant attacks in South Africa are. Specifically the study looked at how lay people’s beliefs about the causes of this type of violence differed from those of the state-sanctioned ‘just crime’ discourse. It showed that the state-sanctioned discourse was unpopular with the general public and identified the most popular explanations used to understand this important issue.

In my research I found that most of the general population identified the supposed harmful conduct of international migrants as the main cause of anti-immigrant violence. Although some population group differences were noted in the study, these differences were not as substantial as may have been expected. This outcome demonstrates how widespread negative stereotypes about international immigration are in the country. These results are confirmed by public opinion research that has taken place in the last few years. This shows that such stereotypes are neither limited to, nor meaningfully more prevalent in, poorer black communities. More research is needed to understand the population group differences observed in this study. However, my results show that, on the whole, threat-based explanations were popular amongst all population groups in the country.

The main reason for anti-immigrant violence put forward most often in my study was economic competition. This interpretation must be understood in the context of the country’s current economic situation. Despite the miracle of democratisation and the end of white minority rule, life in South Africa remains difficult for many. Poor governance, lacklustre investment, and public corruption have undermined economic growth in the country. The economy has struggled to attract investment since the 2008 global financial recession and investor confidence has been low. The official unemployment rate has also worsened over the last 10 years. Although the official unemployment rate is 28% in early 2019, the expanded unemployment rate (which incorporates discouraged-job seekers) was much higher at 38%. Due to a lack of decent work, millions in South Africa struggle to put food on the table. Almost sixteen million people were estimated to be living below a food poverty line of 547 (approximately £29) per month in 2018 which is up from about fifteen million in 2008 according to data from IHS Markit.

It would appear that for a significant share of the general public attacks against immigrants are interpreted as a form of crime prevention. This implies that, for this segment of the population, the violence is a form of vigilantism and is viewed as part of an understandable (if, perhaps, inappropriate) effort by community members to ‘purge’ their neighbourhoods of crime. This finding was unanticipated as crime-related explanations for anti-immigrant violence have not received significant representation in the media or the speeches of policymakers. But then many South African communities are beset by safety concerns and crime rates remain high. According to reports from the South African Police Services, there were 19,016 homicides in the 2016/7 financial year as well as 156,450 cases of common assault and 61,078 cases of aggravated robbery. Reports of drug-related crime have grown exponentially in the last 20 years. There were only 40,363 cases of such crime in the 1996/7 financial year compared to 292,689 in the 2016/7.

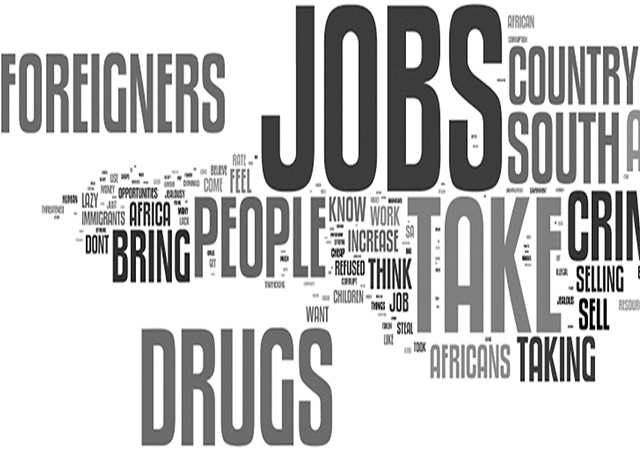

Many people in South Africa seem to believe that aggressive antipathy towards foreigners developed out of self-interest – a ‘rational’ reaction to the size of the threat posed by this outgroup. However, there is no evidence to support the belief that South Africa’s international migrant communities are a significant cause of crime or unemployment in the country. A recent World Bank study has shown that international migration is, on the whole, beneficial for the South African labour market. A number of studies have found that small foreign-owned businesses help create jobs for native-born South Africans. A recent comprehensive quantitative study of police station data by Kollamparambil has shown that there is no clear and significant link between international migration and crime rates in South Africa. Depictions of the foreigner as a ‘criminal’ or ‘job stealer’ are, however, a common idiom in the collective South African imagination. These depictions have been well long been represented in the country’s popular media as studies by Danso and McDonald have shown.

Given how unpopular the ‘just crime’ discourse is in South Africa, it is worth asking why the government backed this interpretation for the last 10 years? I believe that the ‘just crime’ reading of anti-immigrant violence had certain advantages that explain why the Mbeki and Zuma Administration adopted it. This interpretation allowed the state to label perpetrators of the attacks as ‘inauthentic’ – as separate and distinct from South Africans as a whole. This labelling shifted the blame for the anti-immigrant violence onto a shadowy collection of unknowable illicit perpetrators.

Steven Gordon is with the Human Sciences Research Council, Democracy, Governance and Service Delivery Programme, Pretoria, South Africa.