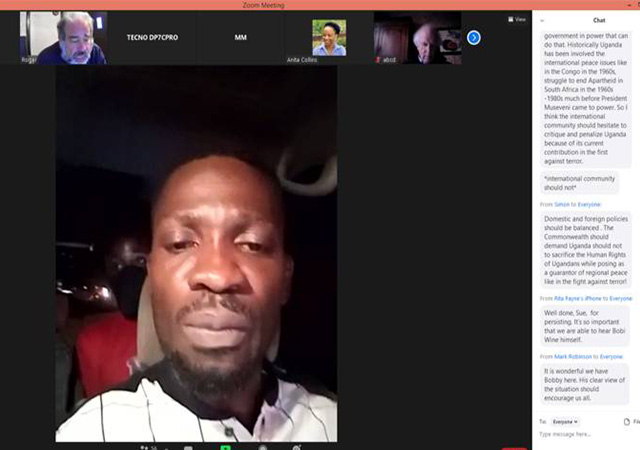

Bobi Wine at a ICwS discussion focusing on Uganda and the Commonwealth held on 25 February. [Roger Hearing in the top left-hand panel]

Bobi Wine at a ICwS discussion focusing on Uganda and the Commonwealth held on 25 February. [Roger Hearing in the top left-hand panel]

“We call on the Commonwealth to call Museveni to order”. That was the message from Uganda’s opposition leader Bobi Wine who made an energetic 20-minute contribution to a 25 February seminar on Uganda and the Commonwealth organised by the Institute of Commonwealth Studies (ICwS).

The 39-year-old singer-turned-politician joined the ICwS seminar entitled Neither Free Nor Fair’? The Ugandan Elections of January 2021 for the final part of its deliberations on the role the Commonwealth could play following Uganda’s general election on 14 January.

According to the country’s electoral commission, five-term President Yoweri Museveni won 58.3% of the presidential election vote while Wine [real name – Robert Kyagulanyi Ssentamu] took 35.8% of the vote. Bobi Wine and his National Unity Platform (NUP) have rejected these results but announced the withdrawal of their Supreme Court challenge in February.

Bobi Wine answered questions posed by former BBC and Bloomberg presenter Roger Hearing and attendees at the virtual ICwS conference. Wine’s lively two-way was zoomed into the discussion as he and his team appeared to be travelling in a large car somewhere in Uganda. His contribution gave a sense of a man, literally, on the move and on a mission.

He said that he had campaigned in the run-up to elections in a bullet-proof vest, that more than 100 civilians had been “massacred” and that the military had taken over the campaign. Bobi Wine described the poll as “the most rigged election since independence”.

He stated that the general elections had been marred by violence and irregularities but he explained that he had discontinued the challenge through the courts because of the “outright bias” shown by judges since the poll. Wine said that to challenge the results would have “no real hope” as the judiciary met publicly and privately with President Museveni. “We opted out of the Supreme Court and we are taking this to the court of public opinion,” Mr Wine told the panel session. He said his party was calling for “civil disobedience” and activities “within the law”.

“We are confident in the people of Uganda….to communicate their dissatisfaction with the dictatorship,” he said. When pressed, he declined to give details, saying that he could not speak publicly about preparations for civil disobedience under a military dictatorship. “Not all of us can be arrested,” he said. He added that the people of Uganda would continue their activities even if some of his supporters were detained. In answer to questions from other conference participants, Bobi Wine said that the internal population and the international community needed to exert pressure on Uganda.

Commonwealth “attention”

Asked about a role the Commonwealth could play, the opposition leader said: “The Commonwealth can, first of all, give us their attention.” He added: “When we have the Commonwealth’s attention, there’ll be limits on abuses.”

On specific steps, Bobi Wine suggested suspension of Uganda from the Commonwealth. He described the Commonwealth as “united in values” as he called for the organisation to impose sanctions on those who abused and refused others’ rights. He said that the Commonwealth needed to make them “accountable” – those he described as seeing themselves as “above national and international law”. He suggested that isolation was one approach. He also called for continued support from the Ugandan diaspora which, he said, had “sponsored” the opposition’s election campaign. Bobi Wine said that the diaspora had kept the focus on Uganda even when the internet had been shut down during the election campaign.

He called on the Ugandan diaspora to protest, to hold their governments to account and encourage them to hold Uganda to the same Commonwealth values as the rest of the organisation. “Democracies should not tolerate dictatorship in any way,” he added.

Asked what the Commonwealth Secretary-General could do, Bobi Wine said that she should join the world in calling for an audit on the election and an investigation into human rights abuses. Wine said that he thought the Commonwealth was “powerful enough”.

Ahead of the general election, Secretary-General, Baroness Patricia Scotland had issued a statement urging all parties, their supporters and security agencies to “shun violence, to expend all efforts to promote peaceful participation in the democratic process, and to ensure that the rule of law, justice and accountability prevails”.

After his appearance at the Institute’s February session, discussant and Institute Senior Research Fellow, Sue Onslow, described Bobi Wine as a “remarkably resilient politician”.

Outstanding recommendations

Before the Ugandan opposition leader had joined the session, there had been discussion about the role the Commonwealth could play in what Dr Onslow described as a “diminution of respect” for human rights over the years. Panellists spoke of the erosion of media freedom and systemic irregularities during the election campaign. Oryem Nyeko of Human Rights Watch Africa Division said that “the opposition had been able to exist but the space in which they operate is increasingly constricted”. Others described the continued harassment of political opponents and emboldened attempts to get away with more and more through each segment of Uganda’s electoral cycle.

Panellists explored the role of media freedom which Sue Onslow described as “the canary in the goldmine”. One contributor outlined the need for the Commonwealth to embrace media freedom principles as part of a codified attempt to hold Commonwealth countries accountable.

The seminar heard that, unlike previous recent elections, neither the Commonwealth nor any other international observer group had received an official invitation from the Ugandan government to be present at the elections. Consent of both government and opposition parties is necessary before impartial observation can take place. Even so, former Commonwealth observer at the 2016 Ugandan elections, Mark Robinson, remarked that the Ugandan govt had failed to implement the recommendations of the 2016 Commonwealth Observer Group.

Institute director Philip Murphy said that the most effective approach would be to “buttress civil society groups who are actually doing the heavy lifting” on rights abuses. He said that the new technology could be used more effectively to connect with activist grassroots group. Professor Murphy spoke of the need for “Commonwealth strength”, rather than the Commonwealth Secretariat playing this role. He spoke of Commonwealth associations and parts of its network providing “ongoing solidarity” for civil society work and being a focus on publicising human rights abuses and freedom of expression issues. Looking at the wider Commonwealth, Professor Murphy said that as the organisation had moved on from values which had been implicit in the past, the grouping needed to make its values more explicit. He said that, in this setting, even if a Commonwealth country chose to withdraw over threatened sanctions, Commonwealth organisations could continue to work with civil society networks and at civil society levels to help citizens in such countries.

Debbie Ransome is the Web Editor for the Commonwealth Round Table. Thanks for additional information from Round Table’s Stuart Mole.

Interview with Bobi Wine [courtesy of the Institute of Commonwealth Studies]:

Catch up with the full session on podcast.