The country is facing an unprecedented humanitarian catastrophe after the remote Pacific archipelago was hit by the worst cyclone in its history, with the entire population of 267,000 people affected to some extent on all 65 inhabited islands, hundreds feared killed in the storm, and thousands left without shelter or water. Reuters reported witnesses describing storm surges of eight metres washing away roads and bridges. All communications were lost with outlying islands. A Red Cross spokesman called the situation ‘apocalyptic’.

Cyclone Pam, a category-five storm, had left the country ‘flattened’, according to rescue workers flying over the volcanic islands, with winds of up to 270km (160 miles) an hour, and gusts up to 340km an hour seriously damaging 90% of homes in Vanuatu’s capital, Port Vila, Oxfam Australia reported. ‘This is likely to be one of the worst disasters ever seen in the Pacific,’ said Colin Collett van Rooyen, Oxfam’s Vanuatu director.

Thousands more were affected in nine countries across the region, according to the New Zealand Red Cross. In Solomon Islands and Fiji, emergency response teams were activated and initial relief supplies put in place. Assessments were also being carried out in Tuvalu and Kiribati, where huge sea swells caused significant damage, and the situation was being monitored in the Marshall Islands, Micronesia, Palau and Papua New Guinea. Extraordinarysatellite pictures of four cyclones sweeping through the south Pacific give some idea of the forces of nature that had battered the small island nations. Aid officials said the storm was comparable in strength to Typhoon Haiyan, which hit the Philippines in 2013 and killed more than 6,000 people, Reuters reported.

The prime minister of Tuvalu, Enele Sopoaga, said nearly half of the population had been displaced by Cyclone Pam, Radio New Zealand International reported, and Unicef warned that at least 54,000 children had been affected in Vanuatu. ‘We have no power or running water and are still not able to move around freely,’ Collett van Rooyen said. ‘The scale of this disaster is unprecedented in this country.’

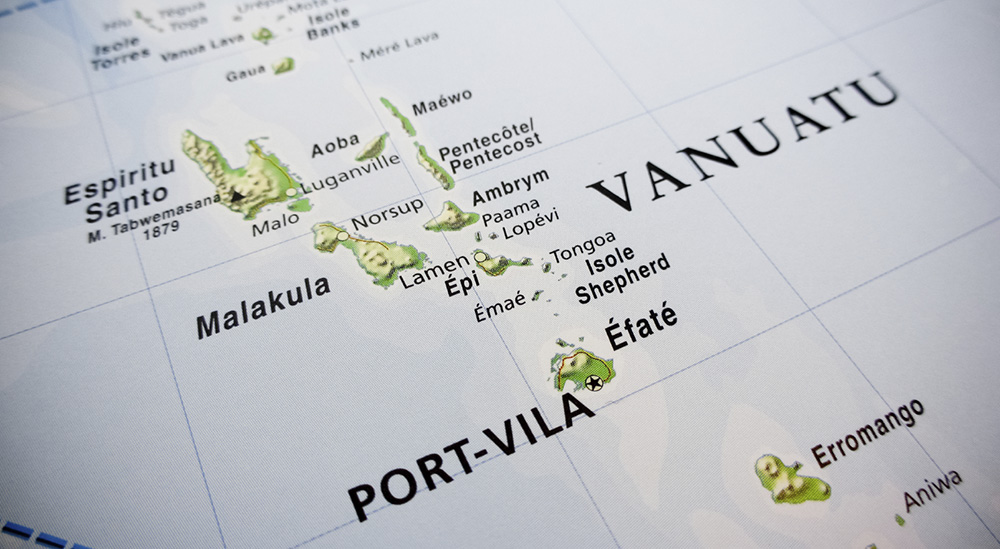

The situation was particularly dire in the outlying islands of Tanna and Erromango. The Guardian reported that a pilot who flew to Tanna, an island of 30,000 people, said there was no drinking water, all of the corrugated iron structures were destroyed, concrete buildings had no roofs and ‘all the trees had been ripped out’, according to Aurelia Balpe, head of the Red Cross’s Pacific operations.

After two days, the airport at Port Vila had been reopened and aid began to arrive in the country on military transport planes from New Zealand and Australia. The French sent a relief team and supplies from New Caledonia. Further afield, the Vanuatuan president, Baldwin Lonsdale, appealed for help as he spoke at a UN conference in Japan (in a bitter coincidence, the summit was on disaster-risk reduction). Fighting back tears, Lonsdale said: ‘I speak to you today with a heart that is so heavy… I do not know at this time what impact the cyclone has had on Vanuatu. I stand to ask you to give a lending hand to responding to this calamity that has struck us.’

Yet this was not an unforeseen disaster: Vanuatu is ranked highest in the World Risk Index. The study estimated the country’s risk of falling victim to a disaster resulting from an extreme natural event at 36.5% – far higher than the second-ranked country, the Philippines, where the risk was put at 28.25%. It has topped this list since 2011.

As far back as 1999, Vanuatu’s submission to the UN climate change conference, which oversees the Framework Convention on Climate Change, noted that: ‘There has also been a significant increase in the frequency of tropical cyclones in the country as a whole over the record period’, although it acknowledged that this trend could have been because of improved monitoring through satellite-tracking technology. In a graph it showed there had been a 500% increase in severe storms over the decades between 1939 and 1998.

It warned that while climate change was likely to decrease annual rainfall, a greater proportion of that rain would fall during storms. ‘Higher intensity rainfall associated with increased cyclone incidence also creates conditions that foster the spread of communicable and water-borne diseases, and may create a need for additional (and expensive) treatment of household water supplies.

‘The infrastructure and fixed assets of both centres are vulnerable to cyclone damage and associated storm surges,’ it noted, calling for planning initiatives to require that infrastructure, such as bridges, roads, wharves and communications, be engineered so as to withstand cyclone, high floodwater flows and very heavy rainfall.

In April 2014 Vanuatu’s climate youth ambassador, Mala Silas, told Radio Australia that climate change was bringing about increasingly erratic weather patterns that were hitting remote island communities hard. Speaking after Cyclone Lusi had swept through Vanuatu, killing 10 people, she said residents on the remote Futuna island were concerned about the impact on agriculture and were urgently seeking better communication systems, as the radio network was inadequate and the mobile network barely existed, and more effective early warning systems to allow locals to prepare shelter and store food before the storms hit.

‘Ben Murphy, of Oxfam Australia, urged the UN conference in Sendai ‘to have Lonsdale’s words ringing in their ears’ as they negotiated a new international framework on disaster-risk reduction. It should be one, he said, that ‘adequately prepares vulnerable nations and communities for the disasters they’re likely to face tomorrow, rather than simply rolling over existing practices which are already visibly falling behind the rising tide of disasters.’

‘He warned: ‘Already, the negotiations in Sendai are calling into question the world’s resolve to take on disaster risk, as sections of the draft text such as strong, measurable targets, linkages to climate change and adaptation efforts, and commitments by developed countries to help finance the global effort are slowly being watered down.’

‘Disasters such as these are likely to become ever more frequent as the effects of climate change take hold, threatening to engulf these small island nations. The Commonwealth should be at the forefront of efforts to avert this grim scenario.