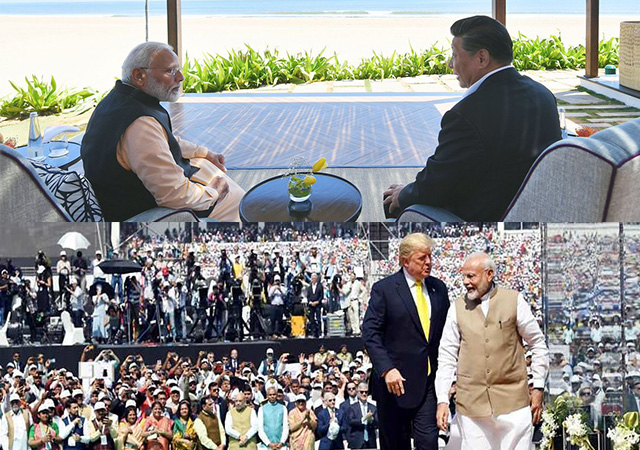

Top: Prime Minister Modi with President Xi in 2019 [Narendra Modi's Twitter feed]. Bottom: Prime Minister Modi with President Trump in 2020 [Narendra Modi's Facebook page].

Top: Prime Minister Modi with President Xi in 2019 [Narendra Modi's Twitter feed]. Bottom: Prime Minister Modi with President Trump in 2020 [Narendra Modi's Facebook page].

[This is an excerpt from an article in The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs. Commentary does not reflect the position of the Round Table Editorial Board.]

The deadly clashes between Indian and Chinese troops in the Galwan Valley region of Ladakh in June have sent Sino-Indian relations into a tailspin. The fact that the Chinese side chose to attack an Indian verifying patrol after agreeing to withdraw their forces, points to their duplicity.

This may also mark a seminal moment in India’s ties with the US. New Delhi is already getting close to Washington in a variety of ways. It has been buying American military hardware and has signed deals worth approximately US$20 billon with the US in the last 13 years. Both India and the US are robust democracies. Besides, the US President and the Indian PM have clearly struck up a bonhomie. Earlier this year, President Donald Trump paid a highly successful visit to India.

Trump has already invited India (along with Australia, South Korea and Russia) to join an expanded G7, which could now become a G11. In another welcome development, the US Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo, had noted in a recent speech that ‘the PLA [China’s People’s Liberation Army] has escalated border tensions with India, the world’s most populous democracy’. This is a welcome statement to emanate from the US.

The current Sino-Indian clashes may also be the final nail in the coffin of their bilateral ties. Although PM Modi and President Xi have met each other many times, this has not translated into substantial progress in bilateral ties. After the Doklam incident happened in 2017 (when Chinese and Indian forces came face-to-face in Bhutan), the two leaders met in Wuhan in 2018, and again the next year in India, in Mamallapuram in Tamil Nadu.

In the current situation, New Delhi’s foreign policy options are limited. The Russians have been unwilling on put pressure on China since their economic ties with China are much deeper than those with India. This clearly marks a break with the past as far as India’s relations with Russia (and formerly, the Soviet Union) is concerned.

In addition, China has been developing a series of ports in India’s immediate neighbourhood as a part of its so-called ‘string of pearls’ strategy. It is also, domestically, rapidly modernising its defence forces and laying more emphasis than ever before on its Navy. Although India has a comparative advantage as of now in the maritime realm, this will not last forever.

India needs a range of options to tackle the threat from China. More attention needs to be paid to increasing domestic economic capacity. The defence budget will also demand an increase. The present round of tensions signifies that the days of the ‘hide your strength and bide your time’ mantra, as enunciated by Deng Xiaoping, are well and truly over in China. Taking on the China threat in the present times will require a series of concerted actions on all fronts from New Delhi – diplomatic, economic and military.

Rupakjyoti Borah is an Associate Professor, School of Law, Sharda University, Greater Noida, India.