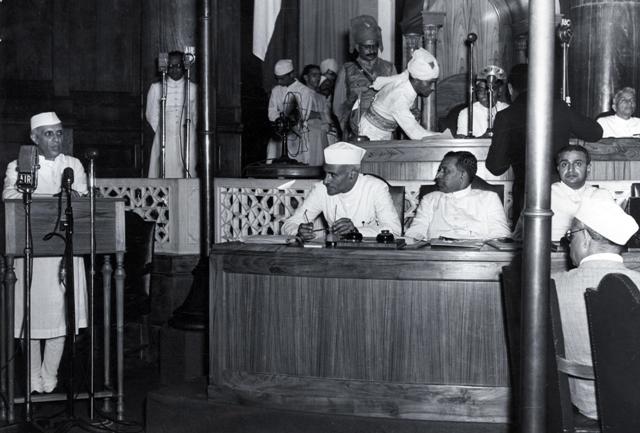

1947: Jawaharlal Nehru declaring Indian Independence in the Constituent Assembly, Delhi. [World History Archive / Alamy Stock Photo]

1947: Jawaharlal Nehru declaring Indian Independence in the Constituent Assembly, Delhi. [World History Archive / Alamy Stock Photo]

[This is an excerpt from an article introducing a special edition of The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs.]

When India became independent in 1947, most political scientists and commentators had little hope that this vast country would stay united, much less maintain a democratic government. Though reeling from the horrors of Partition, with a minuscule economy, a hierarchical caste system, serious linguistic and ethnic divisions, and hotly disputed borders, India proved the pessimists wrong. After seventy-five years, the country boasts the world’s sixth-largest economy, fourth most-powerful military, significant advances in literacy, all while keeping its constitutional system intact. Unlike other post-colonial countries, India suffered no coups or civil wars, although elections and civil liberties were suspended from 1975 to 1977 during the ‘emergency’ of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. Nonetheless, India’s remarkable success reinforced the idea that a multi-ethnic, multi-religious nation could remain a spirited democracy.

The reasons for Indian democracy’s success are much debated. Some factors are deeply structural, others more contingent. For one, India’s dizzying plurality of faith and language groups dispersed rather than stoked communal tensions after independence. The actions of India’s founders also proved momentous. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi or Mahatma Gandhi’s construction of a participatory and grassroots Congress Party created, for the first time in Indian history, a nationwide demos upon which democracy would later rest (Varshney, 1998). The first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, established norms for future premiers, including deference to the judiciary, Parliament, and party consensus (Tharoor, 2018).

Right from the beginning, India’s democratic experience was remarkably aspirational. The Constituent Assembly, which drafted India’s Constitution from 1946 to 1950, boldly committed itself to immediate universal suffrage. In contrast, older democracies like the United Kingdom and the United States only extended the franchise gradually. India’s first general election in 1952 broke international records after 81 million people cast their votes (Ramanathan & Ramanathan, 2017). This decision would have wide-ranging implications for Indian politics and gradually dissolve the Indian National Congress’ electoral hegemony (Kohli, 1992).

The Indian economy at 75

The expanding role of majoritarianism in India

The state of the Indian military: historical role and contemporary challenges

By 1967, a proliferation of parties representing the interests of the poor, agricultural workers, backward castes, regions, and the urban middle classes had significantly weakened the Congress’ hold on the state legislatures. Indira Gandhi’s turn to populism and authoritarianism, culminating in the ‘emergency’ of 1975, was an appeal to and a means of controlling these nascent political formations (Kohli, 1992). However, democracy persisted through its brush with personal dictatorship. Indira Gandhi resoundingly lost the 1977 general election, casting the reins of power into the hands of a short-lived coalition government. Though Congress returned to power in 1980, it could no longer be sure of its dominance over the Indian political system.

The question of Indian unity dominated the 80s as Sikh, Tamil, and Assamese nationalism turned violent, resulting in the assassinations of two prime ministers. Indira Gandhi fell at the hands of two of her Sikh bodyguards in October 1984, following Operation Bluestar. Her second son, Rajiv, though he was in opposition at the time, perished in a bombing conducted by the LTTE (Liberation of Tamil Tigers Eelam), a Sri Lankan terror outfit in 1991. Both killings revolted the wider public and extended Congress’ electoral lease on life (Guha, 2008). Accordingly, the government managed the outbreak of separatist agitation with a mixture of repression for militants and conciliation for moderates, which in the long run proved successful (Jetly, 2008).

Religious violence also reactivated in the 90s with a virulence not seen since Partition. The demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992 sparked a wave of riots across India as well as the grassroots mobilisation of Hindu nationalist organisations (Guha, 2008). It was at this time that the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) began to gain electoral ground, transcending its northern-Brahmin base and attracting more diverse segments of the voting public (Kohli, 1998). Nonetheless, it stopped short of winning a majority in the national parliament. At the same time, Congress saw its support leak to smaller parties representing caste, class, and religious interests. With both parties in flux, India was ruled by a series of unstable coalition governments throughout the 90s followed by two longer-lasting coalitions from 1999–2004 under the BJP and 2004–2014 under Congress.

Unlike other post-colonial countries, India was not simply an electoral democracy but a constitutional one with strong deliberative and independent institutions that possessed legitimacy within society and upheld a tolerant vision of Indian identity as reflected in the Constitution. Autonomous professional institutions like the civil service served as Indian democracy’s ‘steel frame’, through which bureaucrats spoke truth to power and ensured institutional memory in a clamorous parliamentary system. Today, the civil service finds it difficult to adjust to increasing politicisation, demands for political loyalty over merit, unstable tenures, the impact of technology, and polarisation within society (Khosla & Vaishnav, 2016). The steel frame has undergone worrying corrosion, jeopardising the long-term efficacy of the Indian state.

Nigeria and India both face threat of terrorism

India’s place in America’s world under the Biden presidency: decoding the China factor

India–China relations – the present, the challenges and the future

The Hindutva vision of a homogenous, centralised body politic united by shared culture and belief clashes with the reality of India and the pluralism of India’s founders. The Indian Constitution guarantees the equal treatment of all faiths and ensures that the diverse groups that make up Indian society obtain adequate representation in Parliament and the state legislatures. This secular, democratic, and federal pluralism is framed and regulated by strong intermediary, counter-majoritarian institutions like the courts, the civil service, civil society, and the press. As this system begins to degenerate, India appears to be on the cusp of a kind of second founding, a founding guided by an exclusivist ideology that threatens to undo the achievements of past generations. When constitutional norms and the liberal international order are facing backlash around the world, Indian democracy’s future course will be of great significance for the overall direction of global politics in the 21st century.

Today, Indian democracy’s three-quarter century milestone provokes more anxiety than celebration. Clichès about India as the ‘world’s largest democracy’ or an exemplar of secular ‘patchwork pluralism’ no longer grant the easy assurances they once did. Many around the world worry about the backslide from democratic principles towards a de facto Hindu nationalist state. Freedom House downgraded India’s status from ‘free’ in 2020 to only ‘partly free’ in 2021 (India: Freedom in the World 2021 Country Report, 2021). Similarly, the Economist Intelligence Unit lists India as a ‘flawed democracy’, falling from 27th place in the 2015 Democracy Index to 53rd in 2020 (Democracy Index 2020: In Sickness and in Health? 2020).

The institutional decline of India’s Parliament reflects many of these worries. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha sat for 125–130 days in a year. However, throughout the 2010s, Members of Parliament only appeared for an average of sixty-five to seventy days per year. Even the annual passage of bills has markedly declined from over eighty in 1952 to less than forty in 2011 (Singh, 2015, pp. 363–5). Time was when prime ministers and Cabinet Ministers made a point of attending parliamentary discussions; it is now rare to witness heated debates. Sessions have shortened with less time devoted to scrutiny and discussion of government legislation.

Special edition introduction: Falkland Islands – 40 years on

COP26 special edition

Regular use of the Prime Minister’s unilateral ordinances and the Supreme Court’s claim to constitutional guardianship have raised questions about the nature of Indian parliamentary sovereignty. Internal party rules also make legislating a strictly top-down rather than bottom-up exercise. Anti-defection laws bind Members of Parliament tightly to the control of their whips, reducing participation in law-making. As a result, few parliamentarians take the initiative to represent their constituents’ interests through private member’s bills (Singh, 2015). The added fact that there were criminal charges against 186 out of a total of 543 Members of Parliament in the 16th Lok Sabha does little to bolster public trust (“Every third MP in 16th Lok Sabha has criminal charges,” 2014).

This Special Issue on ‘India at Seventy-Five’ aims to explore India’s major accomplishments and continued challenges. Each essay will analyse a specific aspect of national development, including politics, the judiciary, the media, human and minority rights, economic development, education, foreign policy, and defence. The authors largely agree that India has made genuine and far-reaching progress since independence on all these fronts. However, they also share the anxiety that the cumulative weight of institutional inertia, politicised identities, and unrealised expectations will continue to hold India back from its promised destiny as an open, free, prosperous, and vibrant member of the global community.

Aparna Pande is with the Initiative on the Future of India and South Asia, Hudson Institute, New York, NY, US.