[This is an excerpt from an article in The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs.]

While some might see Malaysia’s 15th General Election (GE15) as a critical juncture for political developments or research agendas in Malaysia, my outlook for sustainability and conservation in Malaysia is guarded against the possibilities of not meeting urgent climate change goals, even though there may be better prospects under the new government.

GE15 was contested on the primacy of race, religion and regional autonomy, then on issues of corruption and bread-and-butter issues, rendering environment conservation and sustainable development a relatively fringe issue. This is a double-edged sword – progress will come from policy elites, moving at their respective individual paces. This shields them from the vagaries of politics and moral panics, but at the same time, it does not lend a sense of urgency.

Coming out of the 14th General Election in 2018, activists were hopeful that the new federal Alliance of Hope (Pakatan Harapan, PH) government would be able to move the behemoth of Malaysia’s government bureaucracy towards better conservation and sustainability policy.

Malaysia: The 15th general election and its implications – Special edition

Research Article – Voting behaviour after the collapse of a dominant party regime in Malaysia: ethno-religious backlash or economic grievances?

The then Minister of Energy, Science, Technology, Environment and Climate Change Yeo Bee Yin had the right moves in planning for energy sector reform towards decarbonisation, increasing public transport usage, eliminating single-use plastics, and also beginning work on a Climate Change Act and an Energy Efficiency and Conservation Act. The bipartisan All-Party Parliamentary Group Malaysia on the Sustainable Development Goals (APPGM-SDG) also was formed in late 2019. My personal experience with the Prime Minister’s Department saw greater openness towards access to information reform (Target SDG 16.10).

However, with the emergent COVID-19 crisis and the ‘Sheraton Move’ in February 2020 which led to a 17-month-long new government headed by the National Alliance (Perikatan Nasional, PN), these plans were at the very least deprioritised, if not scrapped. Tellingly, the new government no longer had a ministry which featured climate change as a named portfolio.

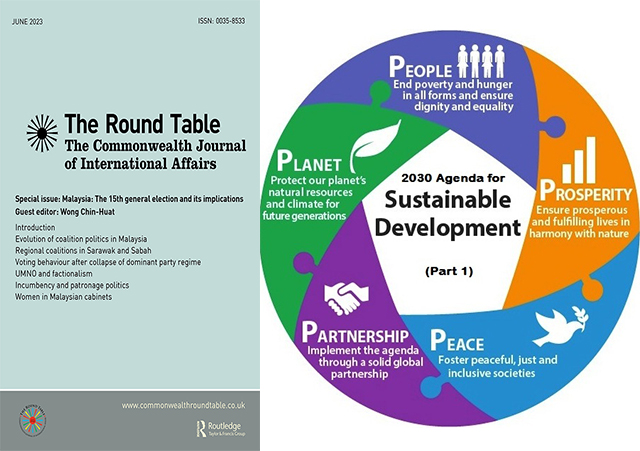

Having said that, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) continue to feature in subsequent government rhetoric and/or official efforts. Malaysia managed to submit its second SDG Voluntary National Review in 2021. The 12th Malaysia Plan, launched under the next government under the National Front (Barisan Nasional, BN), has several sustainability-minded sections. The Prime Minister even announced a MySDG Trust Fund with an initial government contribution of RM20 million, but to date, it is not operational. There was a sense of the Ismail Sabri Yaakob Government doling out as much as possible – even using SDGs rhetoric as a legitimising framework – to buy goodwill before the upcoming elections.

Coming back to electoral competition, while there was broad policy convergence through the various manifestoes – all having some section on the environment or addressing climate change – none of these was on the primary stage of competition. One analysis demonstrates that PH had a more substantive climate proposal than PN or BN. However, if climate change is only a marginal issue, then it can fly under the radar in a tenuous coalition government containing old rivals PH and BN. Furthermore, it may avoid over-politicisation as PN (as the opposition) confronts the government on ethnic and religious issues.

What’s left now is whether this second PH-led coalition government under Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim will pick up the pieces left behind by the first PH government and its successors.

Sustainability (keMampanan) is listed as the first of six values in Anwar’s statecraft narrative, MADANI (progressive in thought, spirituality and materiality) but it remains to be seen whether MADANI lives up to its name, after disappointments in the aspirations and slogans of former Prime Ministers such as Mahathir Mohamad’s Vision 2020 and Abdullah Badawi’s Islam Hadhari (civilisational Islam).

Yi Jian Ho is a Research Analyst, UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network – Asia Headquarters, Sunway University, Petaling Jaya, Malaysia.