The island nation could be returning to the Commonwealth soon after the supreme court unanimously upheld the surprise result in September’s presidential election, paving the way for the inauguration of Ibrahim Mohamed Solih as only the second democratically elected leader in the country’s history. The emphatic win for Solih, known as Ibu – by 16.8 percentage points – had already been declared legitimate by the Maldives Elections Commission. The result is likely to have far-reaching effects on the Maldives’ politics, human rights record, religious freedom and strategic role in the region.

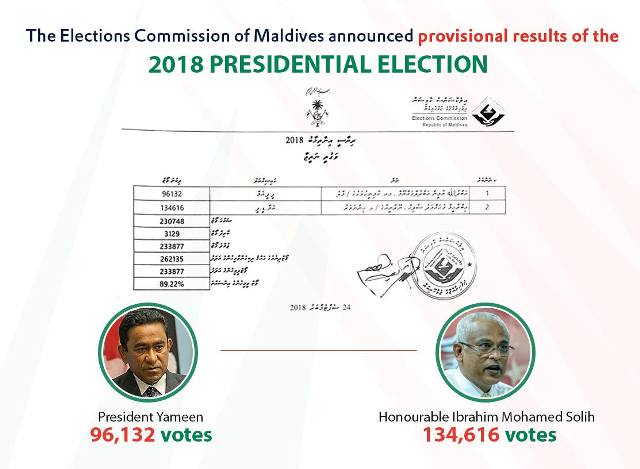

Despite the overwhelming nature of the opposition victory, opinion polls had largely predicted a win for Abdulla Yameen, president since 2012, though as Deutsche Welle noted, most of the opposition media had been ‘muzzled’. One hint of the coming upset on 21 October was the high turnout of 89% across the Indian Ocean archipelago – CNN called it ‘staggering’. The commission said Solih’s Maldivian Democratic Party (MDP) had 58.4% of the votes to 41.6% for Yameen, who succeeded Mohamed Nasheed, the Maldives’ first democratically elected leader, in dubious circumstances in 2012. (Nasheed said he had been forced from office and given asylum in the UK after being sentenced to 13 years on terrorism charges in absentia but a Commonwealth-backed inquiry decided he had resigned.)

Yameen conceded defeat a day after the polls – declaring in a live television address ‘I know I have to step down. I will enable a smooth transition’ – but his Progressive Party of Maldives (PPM) then challenged the result, claiming fraudulent ballot papers had been used to rig the vote, Reuters reported. Even ahead of the ruling, the PPM called it ‘the most farcical election in living memory’ and declared its challenge as essential to restore confidence in the election process. However, the supreme court judgment said Yameen had not proved any electoral fraud occurred and that it still would not have changed the result, given the margin of the opposition victory. Such was the febrile atmosphere before the polls that the Elections Commission had felt bound to issue a strong rebuttal of the ‘false allegations’ that it had facilitated fraud days before voting began, criticising those ‘disseminating such false information and unsubstantiated allegations that could create concern within the general public, and … amongst international partners’.

Ahead of the election, however, fraud was more feared from the government than the opposition. Human Rights Watch said Yameen had become increasingly nationalist and authoritarian, detaining critics, restricting the media and obstructing opposition candidates. Politicians, journalists and bloggers associated with the opposition, secularism or just a more moderate version of Islam were murdered, such as the blogger Yameen Rasheed and the cleric and MP Afrasheem Ali, or “disappeared”, as with Ahmed Rilwan. Under Yameen, the country veered towards a more strident Islamism, The Diplomat noted. No Maldivian is allowed to practice any other religion and non-Muslims are banned from voting. He also brought back the death penalty – the United Nations condemned a move that would make even a child of seven liable for capital punishment under sharia law. Since the 2004 tsunami, when Saudi clerics began to gain influence, the traditional moderate Islam has been replaced by a Salafi and Wahhabi style of Islamic fundamentalism, analysts say. Azra Naseem, a Maldivian at the International Institute of Conflict Resolution and Reconstruction at Dublin City University, told the Irish Times: ‘The changing of an entire population’s religious beliefs and practices within the space of a decade – in ways that roll back almost all progressive ideas that it has embraced over centuries – is extremely serious … Counter-narratives are non-existent.’ As the Economist noted, the last time Yameen had ‘looked on the verge of losing power’, in February, he declared a state of emergency and locked up two supreme court justices, MPs and his own half-brother. ‘His preparations for the presidential election on September 23 appeared just as thorough. The most prominent leaders of the opposition remained in jail or in exile. The government had showered voters with pre-election goodies, such as waiving rent fines and trimming prison sentences. The police went as far as to raid the opposition alliance’s headquarters the day before the vote.’

Meanwhile, the strategic importance of the Maldives, which lies on vital sea lanes, has increased as China asserts itself as the predominant regional power in the Indian Ocean – territory once regarded as India’s backyard, at least in Delhi. Beijing poured money into infrastructure projects as part of its ‘belt and road initiative’ (though always on favourable terms to China), including an $830m upgrade of the main airport and building the $400m “Friendship Bridge” between two of the 1,192 islands. The opposition claimed these Chinese projects accounted for 70% of the Maldives’ debt, costing 10% of the budget a year, and accused Yameen of allowing a Chinese landgrab of 16 islands, according to Foreign Policy. A free trade agreement with Beijing was forced through after less than an hour of debate by MPs, Reuters reported.

The Interpreter, published by Australia’s Lowy Institute, said ‘not only is Solih’s win being hailed as a win for democracy, it could alter the pace and amount of Chinese investment in the Maldives, and shift the power balance between China and India in the Indian Ocean.’ India was delighted with what the Times of India called ‘a potentially game-changing moment in Indian Ocean geopolitics’. Making it clear that he expected a pivot towards Delhi in foreign policy by the Solih government, Nasheed predicted an audit of Chinese-led infrastructure projects in the Maldives and said of Yameen: ‘He just had no idea about the dynamics of great power relations in the Indian Ocean. We will work with India for a meaningful safety and security umbrella.’ The Economist suggested Solih would soon reverse many of Yameen’s more controversial moves, such the re-criminalisation of defamation. ‘And the corruption scandals and unexplained murders of critics that marred his rule are likely to be investigated more thoroughly,’ it added. Nasheed returned to the Maldives from exile in Sri Lanka on 1 November, though ruled out joining the government. India’s Economic Times reported that the former president (a first cousin of Solih’s wife, Fazna) wants to change the system of government to a parliamentary one.

Speaking after his election victory, Solih declared: ‘For many of us this has been a difficult journey, a journey that has led to prison cells or exile. It’s been a journey that has ended at the ballot box.’ Writing in the Guardian, JJ Robinson, former editor of the independent news website Minivan News, agreed that the country had a ‘rare second chance … to make a peaceful democratic transition’. After such a tortuous route back to democracy (Yameen and his half-brother, Maumoon Abdul Gayoom, have ruled the Maldives autocratically for 36 of the past 40 years), it must be hoped that, as Nasheed tweeted, the MDP has indeed ‘pulled the Maldives back from the brink’.