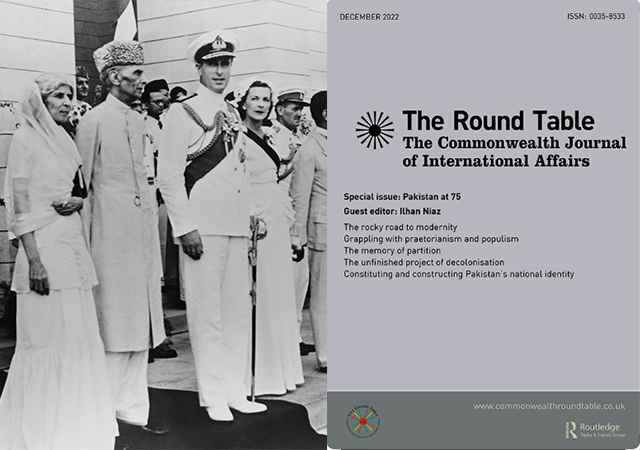

Archive photo: Lord Louis Mountbatten handing over power to Mahomed Ali Jinnah on August 14, 1947. [Everett Collection Inc / Alamy Stock Photo]

Archive photo: Lord Louis Mountbatten handing over power to Mahomed Ali Jinnah on August 14, 1947. [Everett Collection Inc / Alamy Stock Photo]

[This is an excerpt from the introduction to a special edition of The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs.]

As Pakistan marked its 75th year, it faced several potentially life-threatening crises. Imminent bankruptcy stared the country in the face from April 2022 onwards and continues to haunt prospects of recovery amidst the resumption of an IMF programme. Catastrophic floods inundated a third of Pakistan, displaced 33 million people and caused at least US$20 billion worth of direct economic damage (with estimates expected to rise). While the economic and ecological crises wreaked havoc, the April 2022 overthrow of the Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf (PTI) government in Islamabad triggered a constitutional and political crisis that is yet to be sorted out as its leader Imran Khan attempts to return to power on the back of severe criticism from his former allies in the military. And then, the strategic and security fallout of the Taliban victory in Afghanistan has led to a steady increase in terrorist violence in Pakistan, while the clouds of a Sino-US Cold War gather and India–Pakistan relations remain confrontational. Pakistan is a strange state in that while perennially beset by multiple crises, it continues to endure without attempting to resolve any of its underlying problems. The concurrent operation of so many vexing challenges can be understood in terms of five permanent crises by which Pakistan has come to be characterised. These crises are those of epistemology and worldview; constitutional and political order; political economy and development; national security and regional outlook; and national identity and integration.

Special edition: Pakistan at 75

Introduction to Special edition: India at 75

Special edition introduction: Falkland Islands – 40 years on

In terms of epistemology and worldview, Pakistan was conceived as a bid for sovereign power by modernist Muslims influenced by the thought of Sir Syed Ahmed Khan (1817–1898). These Muslims identified the main cause of the decline of their community as being a lack of effective engagement with modern science and ideologies. They hoped that if sovereign powers were entrusted to Muslims who shared their diagnosis, then appropriate steps would be taken to ensure the revival of the secular might of Islam in the region. This was in contrast to traditionalist Muslims who attributed the decline in their community’s secular fortunes to deviations from religious or spiritual principles. Since 1947, however, Pakistan’s experiment with Muslim modernism has been largely abandoned. All major political parties are opportunistically communal in religious matters and share a common practical outlook, which is largely backward-looking, on minorities, women, religious freedom, and the free exercise of other rights. And the state, since 1973, has sought to legitimise itself through an explicitly religious idiom and discourse. This has led to a widespread rejection of the legitimacy of reason, humanism, and science, as appropriate vehicles for guiding the state and society.

As these words are being written, Pakistan is in the grip of yet another political crisis. The cause of recurrent political crises is, at least, easy to identify. Since April 1953, Pakistan’s military (initially aided by the civil service elite) has wielded de facto power over the state. During periods where a semblance of elected government has been allowed, the de facto power has coexisted uneasily with de jure authority. And during periods of overt military rule, the constitutional and democratic window-dressing was dispensed with until popular opposition led to a gradual and phased civilianisation of the exterior of the dispensation. Pakistani civilian leaders have repeatedly failed to demonstrate the acumen and ability needed to restore civil supremacy, while Pakistan’s military leadership has found it impossible to resist the temptation of meddling in the political process. In this context, civilian actors criticise the military when out of favour with it and collaborate when the opportunity arises to take charge of the exterior. Amidst this dysfunction Pakistan careens between arbitrary rule by civilian leaders supported by the military and arbitrary rule directly by the military.

While Pakistani elites have failed to evolve a workable approach towards modernity and achieve a passable consensus on the basics of constitutional and political order, the country’s economy has remained mired in underperformance and stagnation. For the past 50 years, Pakistan has steadily fallen behind other countries in its region and peer group including India, Vietnam, Rwanda, and Bangladesh. It almost does not matter which indicator one takes – per capita income, childhood stunting, gender gap, educational access and outcomes, housing, etc. – Pakistan either struggles to keep its (low) spot or has fallen to near the bottom of all relevant league-tables. Pakistan, in other words, has become a chronically underdeveloped country characterised by a stalled industrial revolution, a rapidly growing population, low labour productivity, and persistent external deficits leading to the government’s repeated trips to the IMF for bailouts. That 75 years after the end of colonial rule, 40% of Pakistani children are stunted owing to a lack of adequate nutrition and access to clean drinking water, is just one of the countless heart-breaking data points. It does not appear, however, that Pakistani leaders are serious about tackling these problems in a comprehensive manner. The goal of every government is to secure sufficient external financing on whatever terms, kick the can of reforms down the road, and try to ride out its tenure.

Ilhan Niaz is Professor of History, Quaid-e-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan.