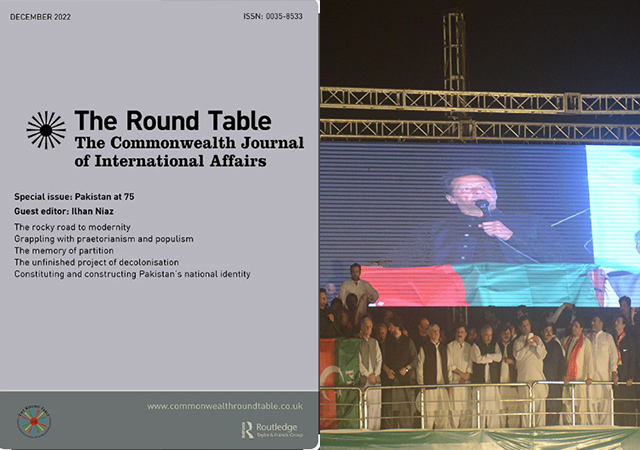

[l] Cover of Pakistan at 75 Round Table Journal special. [r] Ousted Prime Minister Imran Khan speaks to supporters in 2022 [photo: Alamy]

[l] Cover of Pakistan at 75 Round Table Journal special. [r] Ousted Prime Minister Imran Khan speaks to supporters in 2022 [photo: Alamy]

[This is an excerpt from an article in The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs.]

Introduction

Sceptics about Pakistan’s evolution and its journey through an amalgam of domestic and regional crises may wonder about its survival though the country, to them, is still not out of woods. On the contrary, Pakistanis – call them nationalists inhabiting the familiar swaths of patriotic public opinion – consider their country to be a reality given its Indus Valley roots and toiling masses, who despite their dismay with the elite of every shade, refuse to accept any dictum on its vulnerability. Located in a testing geo-political terrain often featuring uneasy relations with its neighbours and having suffered the separation of its most populous wing in 1971, the state is, once again, at the crossroads amidst a host of domestic and external travails, further exacerbated by climatic disasters – not of its own making – and a gnawing economic downturn. Called ‘a palimpsest on the past’ by Salman Rushdie – the controversial novelist with his own familial associations with the country –, also described as ‘one of the most dangerous nations’ by Joe Biden and perceived as a ‘paradox’ by a French South Asianist, Pakistan sails on during its eighth decade on choppy waters, strewn with defiant boulders and subterranean rocks.

Special edition: Pakistan at 75

Research Article – The rocky road to modernity: an assessment of Pakistan’s 75 years

Opinion – Pakistan at 75: a mixed record

Certainly, amongst the post-colonial states, it is a ‘hard country’ defying all those erstwhile analyses which posited it as a nemesis of India with its neighbour itself now bedevilled by a majoritarianism threatening its very societal composition. During the tumultuous months of 2022, several Pakistanis lauded the fact that Bangladesh – the former East Pakistan – was performing enviably in all the socio-economic areas whereas their own country had been left in a blind alley by the generals, clerics and politicians. While India under Modi was seen resembling its western neighbour owing to a rising populism, economic worries in Sri Lanka also caused concerns about their own precarious situation. Pakistan’s enduring ideological and ethnic issues cohere with its rather status quoist infrastructure, sustained by its pampered khaki and civil bureaucracy whereas civil society finds in social media a more effective way of articulating their critique of institutions exhibiting both hope and fear about a populace which is certainly huge, vocal, polarised and no less eager to welcome a systemic overhaul. In foreign relations, it is again an unending transition where neighbouring Afghanistan, after the American withdrawal, is still unstable if not totally trustworthy while Delhi refuses to be accommodative and the U.S., after Imran Khan’s loss of power, appears willing to define its bilateralism with Islamabad largely though Rawalpindi – the latter stipulating the Pakistani Army’s pre-eminence within the polity’s imbalanced infrastructure.

Retrospectively, Pakistan’s enduring challenges could be simplified in reference to the absence of a unifying consensus among the trajectories within the mutually conflictive domains of ideology, authority and ethnic pluralism though its newer generation, economic interdependence within the milieu of exceptional mobility across the Indus regions and a general acceptance of their own separate identity have collectively allowed this state to survive. Successive Pakistani regimes keep trying to inculcate a distinct consensual identity, acculturative and coterminous with West Asian Muslimness while consciously underplaying its Indian legacies; textbooks in a widely subscribed Urdu medium are augmented by a diaspora’s professed self-identification with the Indus lands. In a world of varying and fluid identities, Pakistan is not an exceptional case nor is it the only post-colonial state finding itself at the crossroads of modernist pushes and traditional pulls though, confronted with acute economic issues and internal fissures, it needs to hasten a multi-pronged journey towards an all-encompassing consensus. But as witnessed first-hand during a testing summer of 2022 amidst harrowing floods, Pakistan’s youthful bulge appeared willing to forgive a charismatic and populous figure like Imran Khan despite his less-than-brilliant record in resolving long-standing institutional imbalance. Without a substitutive clarity, Khan’s fiery rhetoric has been critical of country’s ‘establishment’, which he often derides as ‘neutrals’, though for his audience it has always meant the Army generals and a Houdini-like intelligence outfit called the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI). Yet the thrust of his oratory stays reserved for the Sharif brothers who have ruled Pakistan and its biggest province – Punjab – since the 1980s though they too routinely fell victim to khaki highhandedness.

To Khan and his acolytes, these rulers of the past and present Pakistan – including the Bhutto-Zardari clan – are not just instinctively corrupt; they are equally indifferent to the populace and treat the country as merely a vehicle to accumulate more wealth for investments in clandestine overseas bank accounts and properties. While holding negotiations with his American interlocuters, Khan, in his public utterances, was critical of Washington for almost manouvering his ouster in April 2022 which certainly might have helped him gain more listening ears but not without impacting Pakistan’s vital relations with the United States. In the same way, his frequent usage of terms like ‘creating a Medina-like state’ and denunciation of global (read Western) Islamophobes, endear him to a sizeable stratum of this predominantly Muslim society that is not a stranger to widely shared Muslim grievances with the West especially after 9/11. Thus, Imran Khan’s dramatic ouster through a parliamentary vote and the resultant re-energisation of the imbalances among the three proverbial A’s keep replenishing ‘a million mutinies’ within the society and polity that the power elite avoid discussing, much less resolving. While reviewing Pakistan’s contemporary politics, iteration of some of the salient aspects of its history, views about the formation of the country and the contested nature of those above-mentioned three sets of trajectories may help us acquire some grasp of macro context for the ongoing contestations that keep Pakistan hostage to praetorianism and populism.

Iftikhar H. Malik is Professor Emeritus, Bath Spa University, UK.