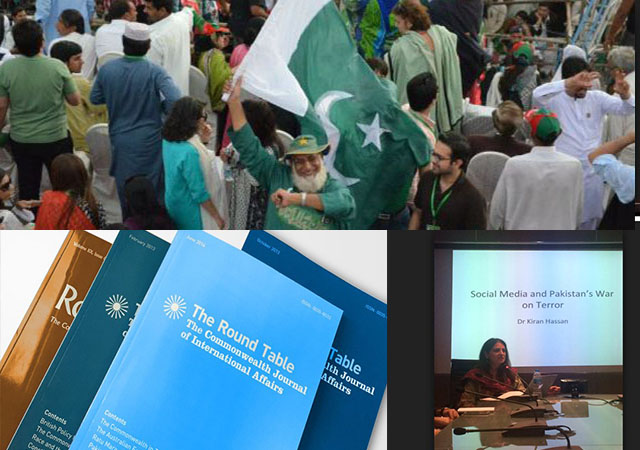

In Pakistan "an atmosphere of panic amongst many journalists making them afraid to report." [Dr Hassan photo by Yaqoob Khan Bangash. Pakistan photo by Kiran Hassan]

In Pakistan "an atmosphere of panic amongst many journalists making them afraid to report." [Dr Hassan photo by Yaqoob Khan Bangash. Pakistan photo by Kiran Hassan]

[Excerpt from an article which appears in a special edition of The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs]

After 11 September 2001, Pakistan’s broadcast media became extremely cautious when reporting on militancy. Indeed, between 2005 and 2010, media houses reporting on terrorist activities increasingly came under attack in the conflict-ridden regions especially Swat,Tank, Bannu and Malakand.

This was particularly true in areas of low-intensity conflict neighbouring Afghanistan. When journalists in the war zone came into contact with the Taliban or other militia, they were either warned to keep silent and exercise self-censorship, or produce pro-Taliban reporting. If such requests were denied or ignored, the Taliban often carried out their threats.

There are numerous cases where journalists reporting on critical issues received death threats. In one instance, Amjad Hussain a senior journalist of the first English-language independent news outlet (Dawn News) had to seek asylum in Australia because of increasing threats by the militants.

These began when he started to investigate sectarian and extra judicial killings, enforced disappearances and human rights abuses targeting the Baloch and Hazara communities. He started receiving threatening phone calls urging him to stop reporting on the killings and kidnappings of Hazara and Baloch political activists or face dire consequences.

Kidnapping of journalists for ransom emerged as a common practice of extortion after Pakistan partnered with the United States in its war on terror. This remained a threat commonly used against foreign media journalists, who covered the activities of militant jihadis.

The abduction, followed by the videotaped beheading of Wall Street journalist Daniel Pearl in 2002, was a particularly shocking event. Death threats and restrictions on freedom of movement and freedom of the press have transformed the Pakistan tribal regions into ‘no go areas’ which has forced many journalists to flee from these areas.

For instance, journalists covering conflicts in north western Pakistan are fearful of Taliban reprisals while reporters in Balochistan are openly threatened by Lashkar-e-Jhangvi and ethnic Baloch armed groups. Journalists are expected to ignore their crimes while simultaneously writing in favour of their cause More recently, journalists in Pakistan’s heartland of the Punjab have also faced threats from the Taliban and Lashkar-e-Jhangvi-linked groups.

Impact on Media Freedom

How does this ugly scenario impinge upon media freedom more generally? While journalists remain highly exposed to threats by militants, they are also at the same time often targeted by Pakistan’s security forces. The security forces operating in the region have frequently misinterpreted journalists’ dedication to their profession and have suspected them of having links to the Taliban.

Detaining journalists is a frequent practice of the security forces.36 The Pakistani military has limited patience for anti-military reporting in conflict regions. This is not entirely malign, as this is also motivated by concern over the dangers to journalists themselves.

As Athar Abbas, a former Director General of DGISPR (Directorate General of Inter-Services Public Relations) explained,

In South Waziristan, the Taliban were attacking and on a rampage…attacking convoys etc….This was a very serious situation and [there were] very intense moments…I did not know how to respond to the media…particularly…I was concerned how to make a very precise and concise statement without going into lengthy explanations….During our war in South Waziristan, a reporter Musa Khan entered the Watta area…this was a time when the military was not there and the intelligence officials were keeping away from the area…somebody pushed the reporter into the area… when the poor chap got killed…the first thing the press did was to point the fingers on the security agencies that they had killed him….We don’t encourage reporters to go into these areas because it is too risky.

Forced reporting is another problem many journalists have to face while covering the conflict areas. The military often expects the media to glorify their operations and present a favourable picture. According to one journalist covering Baluchistan, in 2006 the Pakistan army took several journalists to the conflict zones to cover the anti-Baloch (nationalist) military operation. They were forced to report in the military’s favour and not allowed to ask military officials questions showing their independence.

It was believed that many senior journalists in Quetta and Islamabad were on the payroll of the Pakistani military at that time. The objective was to restrict the flow of information from the tribal areas, a practice which endures to this day. The sensitivity involved in the on-going operations and the nature of terrorism in the region suggest that both the parties in conflict are inclined to keep the media at arm’s length. Consequently, this has created an atmosphere of panic amongst many journalists making them afraid to report as they fear a backlash from militants, criminals, and intelligence agents in the region.

[Dr Kiran Hassan is an independent consultant.]

Related articles:

The Commonwealth and challenges to media freedom by guest editor of the latest special edition Sue Onslow

Indian media: Turbulent times by Nupur Basu

Media freedom in the Commonwealth: Making the commitments real – by David Page and William Horsley