[This is an excerpt from an article which appeared in The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs.]

Muslim-majority countries often face the question of how to reconcile the place and role of religion within the framework of the nation state and a modern westernised system of constitutional ordering. The constitutional battles fought in the wake of independence from European colonial control and occupation have, time and again, centred on this very question. This is certainly true for Malaysia and Indonesia, for example, where matters of religion became a contested focal point in the constitutional deliberations which took place in the wake of independence. The project to establish Malaysia as an Islamic state has been difficult to define – let alone realise. The politicians in that country have proffered conflicting accounts of what an Islamic state is or should be. Numerous constitutional articles and provisions uphold the importance of Islam in the political and legal order.

Major political parties across the political continuum have also headed Islamisation programmes. Yet the Islamic identity of the Federation continues to be a major source of conflict and contestation. The politicisation of Islam has also led to continuing jurisdictional turf wars between civil and sharia courts at a constitutional level. And proposals for Islamisation remain a looming fixture in the political horizon despite opposition from rights and women’s groups in civil society against measures to introduce sharia provisions such as Hudud laws which prescribe Quranic punishments for certain offences. These tensions have provoked riots and violence, threatened religious minorities and heightened communal mistrust and hostilities across the country.

The political identity of the new Indonesian state was also largely undecided upon at independence in 1945. This was a consequence of the many opposing streams of political thought present in the nationalist movement. The need for national unity, however, was pressing and necessary for the legitimisation of a unitary Indonesian state. But the country did not ground its national ideology on Islam despite harbouring the largest Muslim population in the world. The Republic of Indonesia was instead based on five principles, or Pancasila (belief in God, national unity, humanitarianism, sovereignty of the people, and social justice and prosperity). This moral basis for the state was broad and vague enough to acquire some support from competing political groups. Islam did not acquire the status of an official state religion as it did in Malaysia. Nor was the head of state required to be Muslim. The political presence of Islamic groups mounted little resistance to the five principles philosophy or the secular leadership of President Soekarno (1945–1967). Islamic groups were often divided on issues of ideological concern and seldom united on a defined political position. Islamist challenge to the national ideology during the authoritarian rule of President Soeharto (1967–1998) was met with uncompromising repression. By the time Soeharto stepped down in 1998, Pancasila had lost popularity and political traction. Ostensibly, fundamental questions concerning the role and place of Islam remained open and contested. Indeed, efforts to resolve them frequently become a judicial matter in the constitutional courts. The fall of authoritarian rule and the transition to democratic politics also thrust the status of religious sects, such as the Ahmadis, and the limits of constitutional rights on religious freedom into political debate. The post-Soeharto era has seen some of the worst religious violence and sectarian conflict in Indonesian history.

The tense and fragile political and constitutional deliberations which emerged in the aftermath of the Arab Spring uprisings revealed that the problems of situating religion constitutionally persist unresolved to the present day. The Egyptian experiment in constitution-making in the aftermath of the 2011 revolution renewed bitter divisions over the relationship between religion and the state. Political parties in Egypt remained deeply divided on the constitutional place of religion and religious law. The now defunct 2012 constitution, which was a deeply unpopular political settlement at the time, failed to bridge the tensions. Obvious problems stood out. While articles in the document detailed an orthodox interpretation of the sharia as the principal source of legislation and emphasised the functional importance of al-Azhar (the renowned Sunni educational institution of traditional religious learning and scholarship) in the process, the rights and protections afforded to women and minorities remained an issue. Certainly, the centrality of al-Azhar implied a Sunni sectarian agenda and the sidelining of Shiite Islam. Moreover, the 2012 constitution did not create a parallel sharia court system alongside secular courts. The Supreme Constitutional Court (hereafter SCC) decided on all matters of law – including religious law. What remained unclear was whether the SCC was required to take guidance from the legal opinions of al-Azhar or whether it was bound to uphold them.

The 2012 constitution lacked popular legitimacy and its political life was short-lived. As Rainer Grote and Tilmann J. Roder wrote, the document ‘did not implement a clear and coherent concept of the Islamic state’. Its replacement, the 2014 constitution, which was authored under the tutelage of the military regime, ultimately limited the role of religion. It removed any mention of orthodox jurisprudence or consultation with senior al-Azhar jurists in the legislative process, and left the position on Islam and the sharia extremely vague. The main objective of broad provisions on Islam was to stop religious interference in state matters. Al-Azhar maintained its state patronage even if it was stripped of its political influence under the new constitutional framework. But perhaps the most striking feature to control religion came in the form of Article 74 of the new constitution, which expressly banned political parties based on religion. That the Islamist opposition to the regime continues to languish in prison would suggest that a national consensus on the role and place of Islam in Egyptian politics remains a long way off.

The failure of these Muslim-majority countries to settle on a constitutional agreement on Islam is telling. Malaysia appears unsure of its Islamic identity despite enshrining numerous Islamic clauses into its constitution and partaking in repeated attempts to Islamise its laws and institutions. Indonesia, on the other hand, has gone without significant constitutional reference to Islam. But this approach has not settled fundamental questions related to the religious character of the state. The country has been compelled instead to address matters of religion and state in some other way often through constitutional courts. Egypt has dabbled with both approaches without consensus. It has swung back and forth between having comprehensive constitutional provisions related to Islam to symbolic and toothless clauses which relegate religion to a nominal position in the state. All these struggles readily suggest that Muslim-majority countries forced to confront the challenge of negotiating religion in the constitution-making and constitutional reform processes encounter a familiar set of interrelated and somewhat paradoxical questions concerning: (1) the relationship between national and Islamic identities; (2) the role of Islam and the place of Islamic law; and (3) the way in which religious pluralism and the religious identity of the state can be reconciled. How constitutional drafters and reformers should address these issues has no clear or definitive one-size-fits-all solution. This is not surprising since no two countries are the same. But there are important lessons which could be drawn from the experience of individual countries.

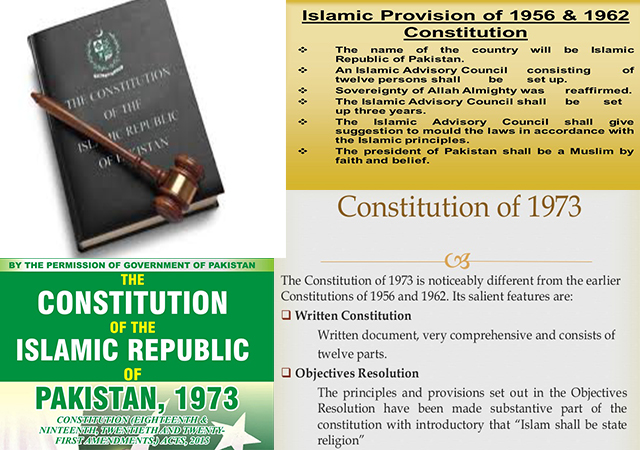

Few states have wrangled with the politics of constitutionalising religion as profoundly and persistently as the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. This paper argues that insights drawn from the Islamic Republic are pertinent as much for contemporary debates on Islam within many Muslim-majority countries as they are for wider debates on religion and politics in the modern period. The Malaysian, Indonesian and Egyptian experiences detailed above are just a few examples that illustrate a common set of patterns, and make the study of Pakistan particularly important and useful. That national identity converges on or eventually orbits Islam in some way or another in post-independence Muslim-majority countries appears to be a global trend. ‘Bangladesh, which separated from Pakistan on the grounds of its Bengali culture’, for instance, is another example of a country which ‘appears to be falling back on the unifying force of Islam’. The struggle they face is not whether or not Islam is constitutionally important. Constitutional preambles invariably assert that it is. The real focus of contestation is what Islam means in practical legal and political terms or in matters of institutional design. This makes Pakistan, a state created in the name of Islam, a country of particular interest.

Imran Ahmed is with the School of Humanities, University of New England, New South Wales, Australia.