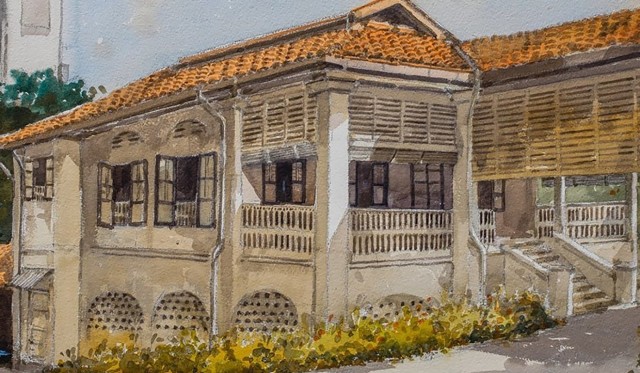

A portrait of the Lee family home by the Singaporean artist Ong Kim Seng, as shown on Lee Wei Ling's Facebook page.

A portrait of the Lee family home by the Singaporean artist Ong Kim Seng, as shown on Lee Wei Ling's Facebook page.

The rare spectacle of a row within Singapore’s ruling dynasty erupting into the country’s tightly ordered public sphere and revealing ‘the dirty family laundry of jealousy and ego’, as the columnist Tom Plate put it, may be drawing to a close. The crisis spiralled out of the dying wishes of the island nation’s founding father, Lee Kuan Yew, whose will and public statements had insisted that his colonial-era house at 38 Oxley Road should be demolished after he died, noting that it lacked foundations, suffered from damp, had cracked walls and was expensive to maintain. The real estate value of the plot, Reuters reported, is about S$24m ($17m), and would be far more if, as Lee urged, planning regulations were relaxed to allow building above two stories. Certainly a nice bequest for his children.

But there was more to it. Laudably opposed to creating a cult of personality around himself, Lee unsentimentally dismissed the idea of preserving his house as a monument, even though it was in the bungalow’s basement that the People’s Action Party (PAP), which has led Singapore since independence, was born. ‘I’ve seen other houses – Nehru’s, Shakespeare’s. They become a shambles after a while,’ he said in 2011, with a wry smile to the camera.

What began as a disagreement over Lee’s legacy, in every sense, escalated into a debate about the nature of the country itself with allegations of abuse of power laid against Lee’s eldest son, Lee Hsien Loong, the prime minister. Joon Ian Wong, writing in Quartz, said: ‘The situation casts a harsh spotlight on the entangled relationships among Singapore’s ruling elite. It raises the possibility of abuse of power, ignoring the rule of law, and overstepping legal bounds by the people at the apex of Singapore society. That’s especially problematic because Singapore prides itself on its meritocracy, clean government, and scrupulous adherence to the law.’

On the day their father’s will was read in April 2015, Lee’s two youngest children, Lee Wei Ling and Lee Hsien Yang, said in a seven-page statement they posted on Facebook that their brother had ‘wanted to state before Parliament the next day that our father had changed his mind and that there was no need to demolish the house at 38 Oxley Road. Naturally we could not agree, as that story was untrue. He was also angry that Wei Ling had an unfettered right to live in the house. He shouted at us and intimidated us … He has not spoken to us since.’

The younger siblings accused Hsien Loong of abusing his power by preserving the house to bolster his own political legitimacy and help the succession of his son as prime minister after him. Wei Ling, a respected neurologist, and the younger brother, Hsien Yang, who heads of Singapore’s Civil Aviation Authority and previously ran the then monopoly telecoms provider SingTel, declared they no longer trusted Hsien Loong as a brother or leader, the South China Morning Post reported. ‘We have lost confidence in him,’ the pair said, adding that they ‘felt threatened by Hsien Loong’s misuse of his position and influence over the Singapore government and its agencies to drive his personal agenda’. Hsien Yang said he would leave the country indefinitely for fear of government retribution, according to the Straits Times.

Alarmed how Singapore’s carefully nurtured image had been damaged by the feud, the prime minister apologised, saying: ‘I deeply regret that this dispute has affected Singapore’s reputation and Singaporeans’ confidence in the government … it grieves me to think of the anguish that this would have caused our parents if they were still alive.’ In a statement given in Parliament during a two-day debate on the issue, Hsien Loong then rebutted his siblings’ accusations and recused himself from any decisions over the house. Three days later, Bloomberg reported, the younger siblings had agreed to their brother’s offer to resolve their differences in private. ‘We look forward to talking without the involvement of lawyers or government agencies,’ they said on Facebook.

Under their father, a tiny state grew from a tropical backwater with no natural resources to becoming one of the world’s richest countries – third in the world for GDP per capita by purchasing power parity, according to the International Monetary Fund. But there was a price to pay for that relentless focus on the economy, stability and orderly governance. Barely heard amid the national mourning after Singapore’s patriarch died in 2015 were more qualified tributes from many observers about a man synonymous with authoritarian capitalism. Human Rights Watch told Deutsche Welle that Lee’s ‘tremendous role in Singapore’s economic development … came at a significant cost for human rights’. With his unscrupulous use of draconian colonial-era legislation such as the Internal Security Act, Lee was unapologetic about his wily, unscrupulous and remorseless style of governance: ‘Between being loved and being feared, I have always believed Machiavelli was right. If nobody is afraid of me, I’m meaningless.’

Singaporeans, and the wider world, mostly appear to accept the erosion of human rights and suppression of dissent in return for prosperity and stability. The party Lee founded, the PAP, has never lost power since 1959, and now controls 83 of 89 elected seats in Parliament. The financial markets were largely unmoved by the Lees’ public quarrel: the benchmark Straits Times index fell 0.1% when the dispute became public, and the Singapore dollar rose. One economist expected no lasting impact ‘so long as it is not perceived that there’s a change in government policy’. Writing in the Round Table, Bilveer Singh, of the National University of Singapore, concluded: ‘The 2015 general elections strengthened the one-party-dominant state in Singapore and the quest for greater political representation was placed on the back burner.’

Referring to the Singaporean terms Kiasu and kiasi, (from the Chinese for ‘fear of losing’, used to describe an overly competitive, selfish attitude), James Chin of Tasmania University, also writing in the Round Table, argued that the island state’s depoliticised development under Lee Kuan Yew led to a ‘social contract under which political liberties were voluntarily sacrificed in return for economic growth and prosperity’.

One interesting aspect of the dispute is that much was played out on social media – the prime minister’s brother and sister had so little confidence in making their voice heard through the media that they argued their case through Facebook. Media freedom was always a casualty of Lee Sr’s authoritarian template – Reporters Without Borders ranks Singapore 151st out of 180 for freedom of the press. It is a model that the Singaporean academic Cherian George called: ‘The pre-eminent example of successful authoritarian control of the press, in that the state has managed to tame the press using declining levels of overt repression.’ As Lee Hsien Yang’s son, Li Shengwu, declared: ‘The Singapore news is heavily controlled by the government. I’m in a position to know.’

A huge irony of the quarrel is that Lee’s children felt obliged to use social media because of a system of tight government control of the press developed by their father: the methods Lee perfected in creating his frictionless modern state came to be used against his own family.