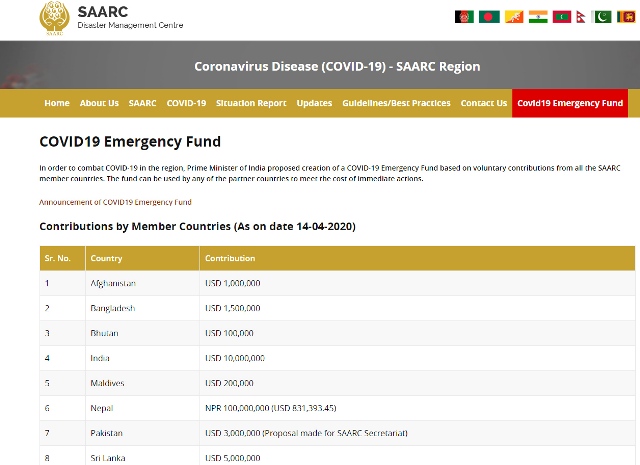

SAARC Disaster Management Centre COVID19 emergency fund website.

SAARC Disaster Management Centre COVID19 emergency fund website.

[These two excerpts are from an article in The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs.]

Significance of regional cooperation in South Asia and the obstacles ahead

To recover sustainably from the pandemic special focus should be put on intra-regional trade within South Asia. It is undoubtedly true that the pandemic has escalated protectionism within the region. India has launched a new initiative in April 2020 known as ‘Aatma Nirbhar Bharat Abhiyan’ (Self-Sufficient India Programme) to make the country self-reliant to deal with the Coronavirus crisis. However, PM Modi has made it clear that ‘When India speaks of becoming self-reliant, it doesn’t advocate a self-centred system. In India’s self-reliance, there is a concern for the whole world’s happiness, cooperation, and peace’ (Aatma Nirbhar Bharat Abhiyan, 2020). In the context of South Asia, the provisions of the South Asian Free Trade Area (SAFTA) agreement and SAARC Agreement on Trade in Services (SATIS) could be strengthened to bring down trade barriers and facilitate trade in services and promote mutual investments (UNESCAP, 2020). UNESCAP analysis shows that two-thirds of trade potential, worth US$55 billion, remains unexploited among South Asian countries (UNESCAP, 2020). The report on ‘COVID-19 and South Asia’ also stated that:

Formation of regional production networks and value chains could create jobs and livelihoods in a mutually beneficial manner. Harnessing this potential would require action on an agenda to strengthen transport connectivity and facilitation at the borders to bring down costs of intraregional trade, and other barriers … South Asian countries [also] need to upgrade infrastructure for modernised cargo tracking, inspection, and clearance and move towards a subregional electronic cargo tracking system besides coordinated development of corridors through a connectivity masterplan linking together key segments of UNESCAP’s Asian Highway (AH) and Trans-Asian Railway (TAR) networks passing through the subregion (UNESCAP, 2020).

COVID-19 has also highlighted the need for regional cooperation for food security in a poverty-driven region like South Asia. The utilisation of the SAARC Food Bank Reserve for the first time reflected this point. SAARC can also be used as a platform for scientific and medical cooperation among the countries of the region. UNESCAP suggested:

Besides keeping their markets open for trade in medicines, health care equipment, and other essential goods and services, South Asian countries could fruitfully collaborate by pooling resources and sharing good practices in digital technologies to improve public health infrastructure and efficiency, developing international helplines, health portals, online disease surveillance systems, and telemedicine, and for development and manufacture of affordable test kits, vaccines, and treatments for COVID-19 (UNESCAP, 2020).

During the current pandemic, India sent a team of medical personnel to the Maldives along with providing them consignments of COVID-19 related essential medicines which made Maldives the largest beneficiary of the Indian COVID-19-related assistance programme in the country’s neighbourhood (Ministry of External Affairs, 2020d). Similar medical assistance was extended to the other SAARC countries of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Nepal, and Sri Lanka.

COVID-19 has shown us that there should be a regional task force within the framework of SAARC to deal with future calamities that might hit the region in the near future. The rise of health diplomacy can also facilitate both bilateral and multilateral initiatives for research in medical sciences within the region. In any case, Indian pharmaceutical companies supply 60% of vaccines to the developing world, especially to low-income countries (Vaidyanathan, 2020).

Way forward

The initiatives taken by the Indian Prime Minister have undoubtedly presented a new ray of hope for the revival of SAARC. However, in order to remain sustainable, this cooperation should not be an issue-based one where the countries unite only to deal with particular issues (i.e., the pandemic in the present context), and not otherwise. This endeavour should rather be a stepping stone to discuss other issues pertinent to the region through the platform of SAARC, which will create grounds for robust political cooperation in future. Moreover, all the countries should make a serious effort to revitalise SAARC, and to do that it is important that all the nations of South Asia should be on board. Isolation of any single state will not help in the successful implementation of the policies of regional integration. For example, by keeping Pakistan aside (for its suspected sponsoring of terrorism), SAARC can never function effectively. Pakistan should also realise that supporting disruptive forces cannot lead to achieving its objectives and therefore cooperating with its neighbours including India is the only solution. That is where the future of the South Asian region lies.

India’s refocus on the region is probably due to the fact that it has also by now understood that, without engaging with Pakistan, the security concerns of the country can never be addressed. Therefore, SAARC should be used as a platform where the concerns of all the South Asian countries can be addressed. For that to happen, political will among the SAARC nations is essential.

It is assumed that the strategic landscape of South Asia is unlikely to change once the pandemic is over because, despite socio-economic problems, South Asian countries tend to focus disproportionately on their strategic and geo-political concerns. In fact, the discord between China and India has reached a new high during COVID-19 with a violent skirmish on the border that resulted in causalities from both sides last year. Vaccine diplomacy, an area where fierce competition between the two countries is anticipated, can be used as a geo-political tool by both the players in the coming months. This current state of India-China relations reflects the hindrances in the prospects of cooperation in the region, where the smaller countries are expected to be dragged into the rivalry between the two regional players. But it is observed that smaller countries in the region see their engagement with both the regional powers (China and India) as a hedge against over-dependence on a single player. Through multi-lateral institutions like SAARC, smaller states can undoubtedly acquire benefits from cooperating and at the same time checking their over-reliance on either power.

In a way the grave threat posed by the pandemic has forced the countries of the region to strike a balance between both traditional and non-traditional security concerns and to come together for the larger good of the region. Strategic competition and geopolitical rivalry should not be prioritised at the cost of human development.

Anchita Borthakur & Angana Kotokey are Research Scholars at the School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, India.