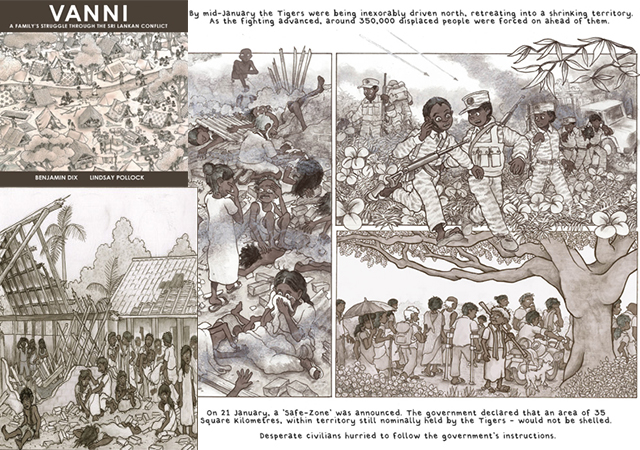

Top l-r: VANNI book cover, a page from the book showing the plight of civilians and a hospital is shelled.

Top l-r: VANNI book cover, a page from the book showing the plight of civilians and a hospital is shelled.

“VANNI: A family’s struggle through the Sri Lankan conflict” by Benjamin Dix and Lindsay Pollock. This review appears on the Riding The Elephant website and is reproduced here with the kind permission of the reviewer.

Benjamin Dix felt it was “a failure of the international system” when he was forced to abandon his job with the United Nations in northern Sri Lanka helping some of the thousands of Tamil people made homeless by the massive Indian Ocean tsunami of 2004.

It was July 2008, and the UN was closing down its humanitarian work in Vanni, the north eastern part of Sri Lanka, because the army’s attacks on Tamil Tiger rebels were getting too close for it to guarantee the safety of its staff.

“It was the abandonment of the people screaming at my office gates, people I’d got to know, that was the trauma,” says Dix. He went on to work in the Sudan after the liberation movement’s victory in 2005, but the trauma lasted for several years.

This has led him to produce a graphic novel, VANNI: A family’s struggle through the Sri Lankan conflict, which covers the human horrors of the tsunami and the stories of people caught in conflict at the end of the island’s civil war in 2009, with tens of thousands homeless and dead.

The book has just been published in India as well as the UK and US – see below for links – and a Tamil edition is envisaged for Sri Lanka.

Since 2012, Dix has run Positive Negatives, a not-for-profit organisation based at SOAS in London University, that uses the graphic novel cartoon strip approach to produce literary comics, animations and podcasts about social and humanitarian issues. “We combine ethnographic research with illustration, adapting personal testimonies and academic work into art, education and advocacy materials,” he says. “PhDs get excited about finding audiences for their work”.

Projects have included some 50 stories viewed by more than 90m people such as a Syrian’s journey escaping to Europe as well as other refugee experiences.

Now there is a £20m commission from the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID) to track various population migrations across the world. Also planned is a film for illiterates explaining how to fill in often bewildering consent forms.

Graphic novels recount horrific events in a way that prevents a reader’s attention being turned off by, for example, a whole page depiction of Tamil refugees being blown up by a bomb explosion, or a mother crying “let me grieve my son” as rockets hail down on her camp.

Such violence in the cartoons does not repel people to anywhere near the same degree as photos or a film, so they keep reading. It is also much more attention-grabbing than mere text and a few photos, and it makes the subjects feel more secure when they are being interviewed.

“It’s very difficult to absorb people’s pain, but converting it into pictures means you don’t need to intrude into people’s privacy,” says Lindsay Pollock, Dix’s co-author who has drawn minutely detailed pictures across 250 pages of the book.

Pollock’s drawings bring to life the horrors of the attacks, and the fear and panic of civilians as they run with their belongings in search of safety. He depicts young men being made to kneel before they are shot, and of a young woman being raped. People drown in rivers, are crushed by collapsing buildings, and are blown apart by bomb blasts.

The idea of Vanni started in Dix’s mind when he left Sri Lanka and later took off as a PhD project. “It grew into a long story and morphed and could have continued to grow, but we needed it to be finished for the 10th anniversary of the war,”says Dix, who initially thought that the seven-year project, part-funded by a £30,000 Arts Council England grant, would be done in six months.

His PhD thesis dealt with “how to take traumatic testimony and turn it into sequential art”, which Vanni does, dramatically.

It tells the story of a fictitious family, the Ramachandrans, and their neighbours the Chologars. They live in Chempiyanpattu, a small village on the northern Sri Lankan coast in the Tamil Tiger controlled area known as Vanni. First their homes are swept away by the tsunami and then their lives are threatened by the growing Sri Lankan assaults on the rebel Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam(LTTE).

Together there are twelve adults and children in the two families, but by the end many have been lost or killed, reflecting the plight of 300,000 refugees, some 70,000 who died (according to the UN), and 140,000 who went missing (testified by the Catholic Bishop of Mannar).

Dix calls the book “non fiction fiction” because it recounts real life experiences fictionalised into the stories of the Ramachandrans, Chologars and others. With Pollock, he travelled by motorbike through Tamil Nadu meeting families. Pollock studied and sketched Tamil features and homes for use in his extremely detailed pictures.

They avoided going to Sri Lanka because they did not want to draw the government’s and security agencies’ attention to people they interviewed. They met Tamil refugees in Geneva, the UK and elsewhere – the 600,00-800,000 diaspora created by the disasters is spread across the world. Dix draws on stories from the time he was living in Vanni, and they studied official reports and talked to experts.

It is clear from the start of the book that the Tamil rebellion, which started in a major way in 1983, is deeply engrained into peoples’ lives. The father of the Ramachandran family had been killed in July 1983 riots in Colombo and a picture of Velupillai Prabhakaran, the Tamil Tigers’ leader, hangs ominously in pride of place on the wall of their home.

There is strong community support for the Tigers and, though they are also feared, there is peer pressure to be recruited and get involved. Young men who return from the rebel front lines in uniform are admired in the village, especially by younger relatives who want to be part of the glory, even though parents fear they will be killed.

“Our stolen Tamil land will be redeemed by our troops – Sea Tigers riding on the sea waves – We are uncontrollable human spinning bombs,” says Jagajeet, one of the Chologar’s sons, as he dons his Tiger uniform. Soon after, he steps on a land mine and loses a leg, the first of many casualties as the story unfolds, gradually revealing the hopelessness of Jagajeet’s dreams.

To begin with, there is hope that cease-fire talks would resolve the Tamils’ demands for more regional autonomy in the Sinhalese-dominated island.

Then disaster strikes in the form of a new Sri Lanka’s hard line president, Mahinda Rajapaksa, and his brother, Nandasena Gotabaya Rajapaksa, the defence minister (who is a candidate in presidential elections in November).

The Rajapaksas opposed the peace process and eventually drove thousands of Tamils to their death in alleged “no fire zones” that were heavily shelled. Their aim was to ensure that every Tamil Tiger was killed, even though that meant the death of thousands of civilians.

That is the story told in this book. The pictures and the narrative are so graphic that readers will not be able to forget what they have seen and read. That of course is Dix’s aim, and he has succeeded.

John Elliott is a member of the Round Table Editorial Board.

UK: New Internationalist, London, ISBN 978-1-78026-515-5 https://newint.org/books/new-internationalist/vanni

USA: Penn State University Press, ISBN 978-0-271-08497-8 https://www.psupress.org/books/titles/978-0-271-08497-8.html

India: Penguin Random House, ISBN 13 9780143449713 https://penguin.co.in/book/graphic-novel/vanni/