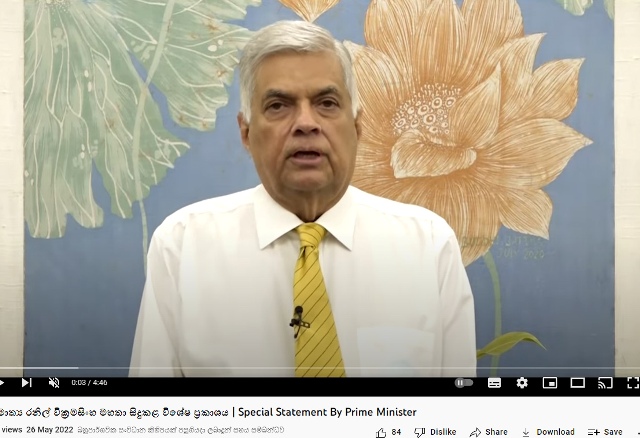

Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe has also taken on board the finance portfolio. [photo: Prime Minister's special statement, May 2022]

Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe has also taken on board the finance portfolio. [photo: Prime Minister's special statement, May 2022]

[This is an excerpt from an article in The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs. views expressed do not reflect the position of the Round Table editorial board.]

At the time Sri Lanka gained independence from the British in 1948, after almost 150 years of colonial rule, the country had a fairly stable financial system. The country’s major export commodities, tea, rubber, coconuts and spices fetched good prices in the world market. Subsequently, gem exports attracted good revenue. With a gradual increase in the demand for services for Sri Lankans to be employed in the Middle-East, in particular, remittances by them to local families became a major source of foreign exchange. In 1977, the economy was liberalised and economic free trade zones witnessed a booming export trade in garments manufactured to high quality by generally low paid workers.

Lee Kuan Yew, widely considered as the founding father of Singapore, studied Sri Lanka’s development model in the 1960s and early 1970s to guide Singapore’s thrust to become a major economic hub. In relation to many socio-economic and educational indicators, Sri Lanka’s performance was second only to that of Japan. At a superficial level, things appeared to be under good fiscal control. This was despite the nationalisation of the petroleum industries and restrictions on the activities of multi-national pharmaceutical companies, to name just two of many measures that provoked international discontent in the earlier decades. A separatist war that began in 1983, when Tamils who constituted one-sixth of the population demanded one-third of the territory to be declared as a separate state, finally ended in 2009 when the Sri Lankan forces captured the militants and regained lost territory. The credit for this victory against one of the most ruthless armed forces in the world that, inter alia, succeeded in assassinating even the Indian Prime Minister, Rajiv Gandhi, was largely taken by the immediate past Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapakse, who then held the position of President with his younger brother, Gotabaya, the current President, holding the post of Secretary to the Ministry of Defence. Gotabaya was then a U.S. citizen, which raised some eyebrows – but a subsequent amendment to the Constitution enabled citizens holding dual citizenship to contest elections.

Mahinda Rajapakse and the entire Cabinet have since resigned and Ranil Wickremasinghe, leader of the United National Party, was sworn in as the new Prime Minister. It is not without significance that Wickremsinghe himself was unable to retain his seat at the last elections and the UNP did not secure any seats except for one position as a nominated Member of Parliament under Sri Lanka’s proportional representation system. Wickremasinghe, who got that seat, became Prime Minister for the 6th time, a record for Commonwealth countries. On 25 May, he was also appointed as the new Finance Minister. The World Bank has announced that no aid will be forthcoming unless the Government provides a credible development programme and budget.

A severely adverse balance of payment conditions has been compounded by allegations over several decades of massive corruption in public procurement and government contracts. Rating agencies have downgraded Sri Lanka and its banks to reflect the current deteriorating fiscal situation. Sri Lanka has been totally unprepared for negotiations with foreign lenders and a few days ago the Central Bank advertised for a Financial Expert and a Legal Expert to assist the Bank with negotiations. The interest burden alone is massive, not only on bonds but also on loans from several countries including China, India and Bangladesh. Estimates suggest a short fall of nearly US$ 51 billion at the present time.

Dayanath Jayasuriya is a President’s Counsel in Colombo, Sri Lanka.