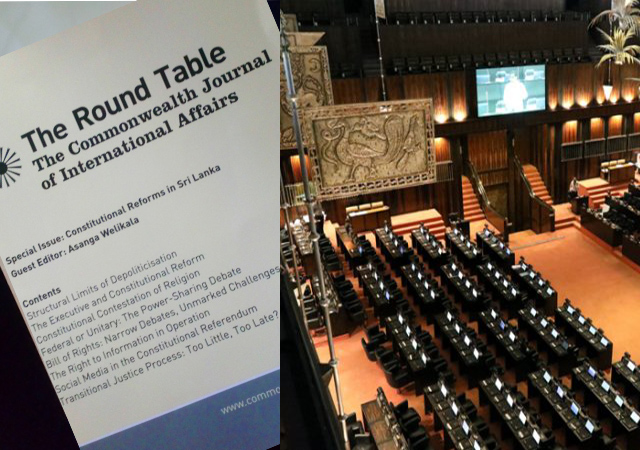

[This is an excerpt an article appearing in the current special issue of The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs.]

In Sri Lanka’s case, the deep entrenchment of the will of an identity group corresponding with two-thirds of the population has incentivised and sustained precisely this kind of decay within institutional structures at all levels.

This type of decay is evident in Sri Lanka even under the post-Nineteenth Amendment era. Two examples may be briefly cited to illustrate this point. First, state law enforcement authorities often remain passive during episodes of ethno-religious violence against minorities. I have argued elsewhere that ethno-religious violence against the Muslim and Christian communities has persisted under the present government regardless of its promises to contain it. Recent examples of such egregious violence include the anti-Muslim riots in Gintota (in the Southern Province) in November 2017, and in Digana and Teldeniya (in the Central Province) in March 2018. In both cases, the police were accused of failing to intervene to arrest instigators of the violence, who included members of the Buddhist clergy. Second, the judiciary has continued to privilege the Sinhala-Buddhist community in the realm of religious regulation. In the 2017 case of Faril & others v. Bandaragama Pradeshiya Sabha & others, the Supreme Court upheld the decision of the local authority concerned and the police to prevent the construction of a Muslim school, following protests by Buddhist monks and local villagers. The Court found that the state had acted lawfully as ‘due consideration’ had to be given to the protests to ‘avoid a crisis situation’. Both examples illustrate the manner in which institutions remain politically incentivised to appease the Sinhala-Buddhist majority. Thus, the processes through which appointments are made do not necessarily determine the extent to which institutions remain politicised.

Admittedly, having non-political actors recommend and approve appointments may play some role in containing politicisation. The standoff between the president and the Constitutional Council over judicial appointments in early 2019 reflects both the value of the Nineteenth Amendment, and the need for more radical reform. The standoff is linked to the extraordinary events of October 2018, when President Maithripala Sirisena purported to dismiss Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe, appoint Mahinda Rajapaksa as prime minister, and dissolve parliament in order to call early parliamentary elections. The plan failed primarily due to the Supreme Court’s interim order staying the dissolution of parliament, and the Court’s eventual determination in December 2018 that the dissolution violated the fundamental rights of the people. The Court of Appeal meanwhile issued an interim order staying Rajapaksa and his cabinet from functioning. Most of the Supreme Court judges, including the Chief Justice, who prevented Sirisena from succeeding in his plan, were appointed under the Nineteenth Amendment. The Constitutional Council specifically approved these appointments. The president’s preoccupation with judicial appointments and his public criticism of the Council in early 2019 are therefore connected to his failed power grab. In this respect, the Council can be credited for playing a role in appointing less partisan judges and containing politicisation to some degree. Yet at no point during the events of October to December 2018 were the fundamental features of Sri Lanka’s constitutional structure actually challenged. The events merely featured an extraordinary plan by one majoritarian power centre to seize power, and the extraordinary response of the legitimately elected power centre – with its own majoritarian tendencies – to restore the status quo. It is important not to overstate this outcome as a triumph of a depoliticisation project. It does not detract from the broader institutional decay that the Nineteenth Amendment has failed to reverse.

The notable transformation of Sri Lanka’s Human Rights Commission following the appointment of a new chairperson and members after the Nineteenth Amendment in 2015 is another success story worth attributing to better appointment procedures. Even the Commission to Investigate Allegations of Bribery or Corruption, which has received little political support in delivering on its mandate, did succeed in May 2018 in arresting the president’s chief of staff on allegations of bribery.The arrest hints at some improvement in terms of the Commission’s political independence owing to better appointment procedures. However, generally speaking, the containment of politicisation through appointment procedures may ultimately be cosmetic, if the institutional structures themselves have decayed due to entrenched majoritarian tendencies. The judiciary, regardless of better appointment procedures and an ‘independent’ Judicial Services Commission, is likely to uphold both the constitutional text of article 9 and the socio-political conceptions of majority entitlement. The police, regardless of better appointment procedures to appoint the Inspector General of Police and the National Police Commission, are likely to refrain from intervening when Buddhist clergy are at the forefront of instigating violence against minority groups. Thus, Sri Lanka’s depoliticisation project is inherently constrained by the deeper structural entrenchment of majoritarianism.

Conclusion

Samararatne rightly points out that Sri Lanka’s depoliticisation project requires a type of reform that is more ‘radical’ than what the Nineteenth Amendment and the Constitutional Council have to offer.40 She argues that such reform must entail a means of distributing political power ‘in a manner that respects diversity’, and that ‘systemic discrimination based on ethnicity and other communal insecurities must be addressed’. Samararatne’s prescribed solution – addressing these problems through ‘public law in a manner which leads to a new logic of citizenship’ – though attractive, is unlikely to succeed by itself. A public law approach to solving this problem is structurally constrained, as long as Sinhala-Buddhist majoritarian ideals remain an entrenched part of the socio-political conceptions of Sri Lanka’s constitutional order.

How then can Sri Lanka’s present constitutional order be transformed? The Sri Lankan experience suggests that reliance on legal institutions and formal textual reform alone may be inadequate, as these institutions will continue to produce politicised outcomes.

Gehan Gunatilleke is with the Faculty of Law, University of Oxford.

Related articles:

Special issue introduction: Constitutional Reforms in Sri Lanka – More Drift?