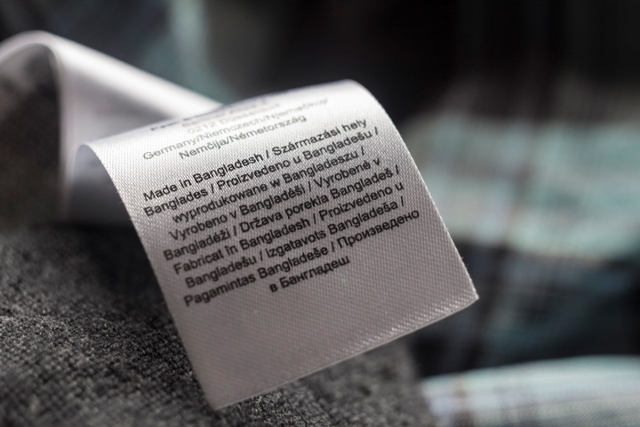

Following Brexit, Bangladesh could face a tax hike of nearly 12% on its exports to the UK [photo: iStock]

Following Brexit, Bangladesh could face a tax hike of nearly 12% on its exports to the UK [photo: iStock]

The Brexit Chill

The potentially disastrous implications for small states of ‘Brexit’, following Britain’s narrow vote to quit the European Union, have been explored in two new papers published by the Commonwealth Secretariat.

In Trade Implications of Brexit for Commonwealth Developing Countries, Chris Stevens and Jane Kennan of the Overseas Development Institute warn that most Commonwealth states are at risk of being ‘crowded out’, largely unable to influence events. They suggest most member states will be restricted to the sidelines of the complex negotiations lying ahead between London, Brussels and key trading nations such as the US, China and India, perhaps brokered by the World Trade Organisation (WTO). With article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty, which formally triggers the two-year process of leaving the EU, not likely to be activated until 2017, six months after the referendum, the uncertainty surrounding the lengthy multilateral trade talks will also have a chilling effect on investment, trade and growth.

The authors’ best estimate is that most Commonwealth states face higher tariffs for exports to the UK totalling €715m (£600m). Bangladesh faces a tax hike of nearly 12% on its exports to the UK, Swaziland’s tax bill could jump 10%, that of Mauritius by 14% and the Seychelles would be hit by a whopping 23.4%, they suggest.

Uncertainties

‘A favourable outcome is not inevitable. It must be explicitly created in an atmosphere of rapid change, limited resources and lobbying from all sides,’ they say. ‘Affected Commonwealth countries will need to press their case actively if their voice is to be heard.’

The threat to the Sustainable Development Goals from Brexit is explored by Mohammad Razzaque, Brendan Vickers and Poorvi Goel in another of the Commonwealth Secretariat’s peer-reviewed ‘Trade Hot Topics’ series. In Global Trade Slowdown, Brexit and SDGs: Issues and Way Forward, they warn: ‘The uncertainties caused by Brexit may weaken the prospects for world economic recovery, with severe implications for developing countries and Least Developed Countries (LDCs).’ The rise of protectionism, as the global economy already struggles to recover from the financial crisis of 2008, has led to an estimated $264bn loss of exports for the poorest nations. There is a lot at stake as the British government re-orientates its foreign relations: the UK’s total goods trade with developing countries was $296bn in 2014, remittances are estimated at $15bn, and official aid at $20bn.

There is some qualified optimism: ‘The UK’s newfound trade policy sovereignty should result in improvements over the currently existing trade deals for ACP [African, Caribbean and Pacific] states and LDCs.’

But the authors also warn: ‘Brexit could mean reduced efforts by the EU on development issues in the absence of a bigger push from the UK … UK’s strong advocacy and lobbying role in ensuring development-friendly outcomes in such areas as global trade, climate change and governance, among others, will remain important and need to be leveraged through enhanced cooperation with such organisations as the ACP Group and the Commonwealth.’