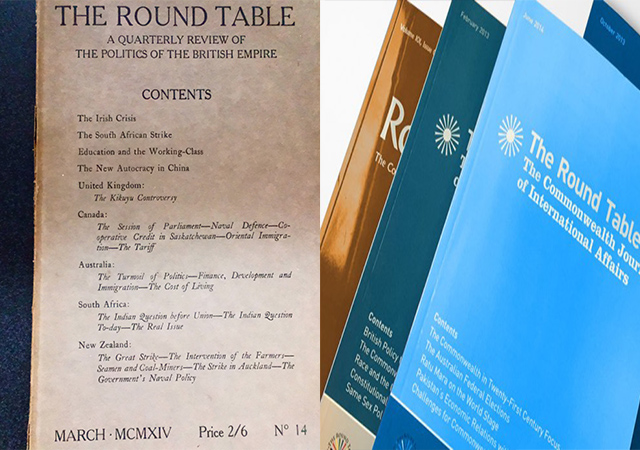

[This editorial is an excerpt from a 1974 edition of The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs. The full article is currently free to access in the Round Table’s ‘From the archives’ series.]

The British general election which took place on February 28th has produced a highly equivocal result. There is inevitably a wide variety of interpretations of the outcome: that it shows a nation paralysed by indecision; that it shows a firm collective resolve on the part of the British to try a new course; that it is evidence of a nation sharply divided between two radically opposed positions each supported by the eleven million votes respectively cast for the Labour and Conservative parties; that it shows a nation bent upon moderation and the pursuit of the middle way represented by the six million votes cast for the Liberal Party. The wider political effects of this result yet remain to be seen: whether the British will shortly return to two party politics, or whether they are now embarked upon a new three party system of coalition politics; whether there is to be a National Government, or whether the Labour Party is destined to rule for the next decade; whether any or each of the three main parties will break apart in the face of new political conditions; whether indeed the United Kingdom itself may be approaching disintegration, in Northern Ireland, in Scotland, and perhaps also in Wales.

This is indeed a wide range of possible effects. The repercussions of this election within the structure of British politics may not in the event turn out to be very great; or on the other hand they may be further-reaching than those of any election since the 1920s. A great deal will depend upon the development of Britain’s economic position— and of the world-wide economic situation—over the next two or three years. This will act upon the relations of the parties, and the state of their mutual relations will in turn affect Britain’s capacity to deal with her economic problems. The condition of the economy will be the principal determinant of the prevailing social and political climate. For it is in the sphere of the politics of the economy that the main arguments between and within the parties are located.

More articles from the archives

‘Australia, security, and the Pacific Islands: from Empire to Commonwealth’ by Richard Herr

‘Common Grounds? Strategic partnerships for governance in the Commonwealth of Nations and the Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie’ by Mélanie Torrent

It is, of course, in this sphere that we find laid down the circumstances which surrounded the dissolution of the late Parliament—the first ever to occur during a national strike in a fundamental industry, and the first since 1931 to be prematurely dissolved at the request of a Prime Minister with a working majority under the pressure of events outside Parliament. The origins of these circumstances may be traced back at least as far as the decade of the 1960s when the main lines of the present political debate about the condition of the British economy began to emerge.

During the 1960s the central problem of the British economy was diagnosed by all parties as being a combination of sluggish growth and a persistently weak balance of payments. Between 1964 and 1967 the Labour Government of the time attempted to solve this problem by means of a mixture of “planning” and incomes and prices restraint. At the same time the Conservative opposition developed an alternative philosophy according to which growth was to be promoted by the restoration of incentives, and by the reduction of the economic role of the state and the “liberation” of the economy. In 1967 the persistence of the balance of payments deficit at last drove the Labour Government into devaluation and heavy deflation. In these circumstances the statutory incomes restraints adopted in 1966 were no longer deemed to be necessary, and in 1969 they were abandoned in the expectation that the trades unions would accept Mrs. Barbara Castle’s proposed legislation to regulate and restrain the use of their bargaining power. These proposals were, however, withdrawn later that year because of the resistance of the unions. And during the period 1968-70 they began to react to Mr. Roy Jenkins’s deflationary policies by pressing for, and securing, very much larger wage settlements than had previously occurred in British industry.