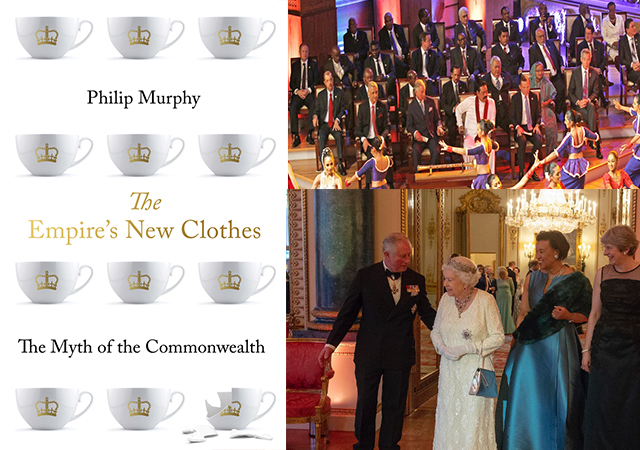

Clockwise: Philip Murphy's book cover, the opening of the 2013 CHOGM and a dinner at Buckingham Palace during CHOGM 2018 [photos: ComSec on Flickr]

Clockwise: Philip Murphy's book cover, the opening of the 2013 CHOGM and a dinner at Buckingham Palace during CHOGM 2018 [photos: ComSec on Flickr]

April 2018 saw unaccustomed media coverage of the Commonwealth. At the beginning of the month, the XXI Commonwealth Games opened on Australia’s Gold Coast. There were an equal tally of medals won by male and female athletes and the integration of able and Paralympic athletes was striking. Though far from being a global Games, world records tumbled. Unusually, politics has featured, with English diving champion, Tom Daley, urging changes to the archaic and oppressive laws which deny equal rights on LBGT issues in many Commonwealth countries.

A few days after the Games’ closing ceremony, the biennial intergovernmental summit convened in London (the first such gathering in the UK for over twenty years). The high turnout of Heads of Government was less an indicator of the organisation’s contemporary vitality and more a sign that the Queen’s offer of Buckingham Palace and Windsor Castle for significant parts of the summit had proved particularly attractive to Commonwealth leaders and their spouses. At the end of the week, the Commonwealth’s presidents and prime ministers dutifully agreed that Prince Charles would succeed his mother as the organisation’s next Head – though no vacancy is currently in the offing.

Among this calculated pomp and splendour came publication of Professor Philip Murphy’s latest book: “The Emperor’s New Clothes: the Myth of the Commonwealth“ (2018, C. Hurst & Co, London). Murphy is a distinguished historian and Director of the Institute for Commonwealth Studies at the University of London. As a Commonwealth sceptic, why he should have taken on his current role is one that even he struggles to explain. There was no gap year spent cycling across Malawi, no father in colonial service in Malaya. His childhood was spent in Hull and ‘overseas’ was summer holidays on the Isle of Man.

To make matters worse, his arrival at the Institute in 2010 coincided with a particularly low point in the Commonwealth’s fortunes. He was stung by the Commonwealth‘s disastrous decision to hold its 2013 summit in Sri Lanka, in the wake of the bloody end to that country’s long-running civil war. Worse, as summit host, Sri Lanka’s autocratic and human rights-abusing president, Mahinda Rajapaksa, automatically became the Commonwealth’s chair in office, an act which severely damaged the Commonwealth’s credibility as an upholder of fundamental human values.

When the Commonwealth became involuntarily entangled in Brexit and the British 2016 referendum, Murphy’s anger knew no bounds. He is clearly a man on a mission, and this he spells out on the opening pages of his book. The Commonwealth, he says, has become a ‘mirage’, having “lost almost all the limited significance it once possessed”. Consequently, if post-Brexit ‘Global Britain’ is building its future in part on a revived Commonwealth, then – muses Murphy – we must be in more trouble than he originally thought.

As the respectable scholar that he is, a lot of Murphy’s writing is cogent and entertaining. There are criticisms of the Commonwealth which are valid and which many of us would recognise and accept. His chapters on colonial guilt and on the British monarchy’s Commonwealth role are particularly thought-provoking. But he also displays a determination to pursue the negative and to ignore evidence that might counter his single-minded and deeply anglocentric narrative.

At times, he becomes wildly unbalanced. The Commonwealth Association, composed of former staff, for example, comes in for special scorn as true-believers, “a kind of sect”, composed of swivel-eyed ‘second comers’. He suggests – but never actually alleges – that the Commonwealth’s sorry approach to Sri Lanka in 2013 was the result of ‘institutional capture’, principally as a result of the activities of Sri Lanka’s tenacious High Commissioner in London. Worse, he implies that Commonwealth non-governmental organisations were also complicit – and did so for financial gain. He produces not a shred of evidence for this outrageous calumny.

On Brexit, Murphy admits that Commonwealth governments almost universally wanted the UK to remain in the European Union. But he then links the organisation to Nigel Farage unveiling a nasty anti-immigrant poster, remarking that its imagery sat uneasily with “the Commonwealth’s long history of anti-racism and its celebration of ethnic diversity”. He throws caution to the winds in concluding that the Commonwealth is “increasingly being commandeered by a grim collection of charlatans, chancers and outright villains”. He ends: “Our old comfort blanket has become toxic. It’s time to grow up and set it aside”.

At the beginning of the year, a retired FCO diplomat, Martin Hatfull, mused that the Commonwealth was “more an organism than an organisation “. Hatfull, a former British Ambassador to Indonesia , was a key British figure in the organisation of the 1997 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM) in Edinburgh. The Commonwealth organism, in its different elements, demonstrates an inexplicable capacity for renewal, and this Murphy does not address. Instead, he predicts that the Commonwealth will wither through inertia and atrophy – but doesn’t explain why South Africa, Pakistan, Fiji, The Gambia and – in the last month – Zimbabwe should want to rejoin an organisation which they at various times precipitously and angrily left.

Murphy therefore begs the question: whose Commonwealth myth?

Stuart Mole is the former Chair of The Round Table and one-time Director-General of the Royal Commonwealth Society. He has previously served as Director of the Secretary-General’s Office in the Commonwealth Secretariat.