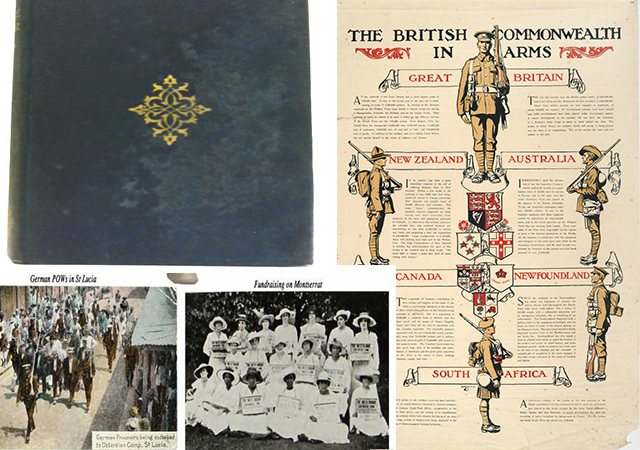

Clockwise: The Empire At War, The British Commonwealth in Arms

[poster: Canadian War Museum], The Caribbean's Great War [West India Committee poster].

Clockwise: The Empire At War, The British Commonwealth in Arms

[poster: Canadian War Museum], The Caribbean's Great War [West India Committee poster].

In a 2014 edition of the Round Table: Journal of Commonwealth Affairs, Ashley Jackson of the Defence Academy of the United Kingdom,wrote an article on The Empire At War by Sir Charles Westwood Lucas (1853–1931), a Colonial Office civil servant and historian. The Empire At War charted the war histories of the imperial ‘big five’—Australia, Canada (including Newfoundland), India, New Zealand and South Africa—are well documented. India sent 938,000 men overseas, Canada 458,000, Australia 332,000, New Zealand 112,000 and South Africa 136,000 (excluding non-whites). These excerpts also look at the contribution of other parts of the then Empire from territories in the European region to the West Indies.

Section one was on Gibraltar, and followed the familiar format of summarising the emergency measures taken on the outbreak of war, censorship provisions, food supply challenges, the war’s impact on the colony’s import and export trade and finances, and war relief fund contributions. This latter category is one of The Empire at War’s most useful features, capturing the array of war-related funds that the people of the colonies contributed to or initiated. Seventy-six Gibraltarian men joined British forces, but as with many other colonies, the manpower recruited to perform civilian war-related tasks was more significant. Gibraltar’s Admiralty dockyard and naval establishments, for instance, employed 2,350 locals, a very large proportion of the adult male population. Like many colonies, Gibraltar had particularly valuable services to contribute to the prosecution of the war. During the conflict (and not counting minor repairs) its dockyard repaired or refitted 350 warships and repaired 80 merchant vessels. It supplied 1,655,000 tons of coal to 5,535 warships and 2,135 merchantmen. To protect its maritime assets, wartime defensive armament work included the mounting of nearly 1,000 guns, and the Rock also housed prisoner of war camps.

Further east in the Mediterranean, Malta was an important strategic asset because of its position in relation to the sea routes connecting Britain with the east and because of the scale of military operations in the region brought about by the war against the Ottoman Empire. The King’s Own Malta Regiment of Militia numbered 3,393 men and formed part of the colony’s garrison, as did the Royal Malta Artillery (1,032 men) and the Royal Engineers Militia (136 men). A further 800 Maltese joined the air force. In total over 15,000 Maltese served in the military in some capacity, 7,000 of them in the Maltese Labour Corps, which sent thousands of men overseas, to places such as Salonika, Italy (a mining company), and Gallipoli (stevedoring companies). A further 1,500 Maltese performed motor transport tasks for the Army Service Corps. On the naval side, 15,900 Maltese served with the Royal Navy and in its shore establishments.

The third British territory in the Mediterranean was Cyprus, still formally a Turkish territory when war broke out though quickly annexed to the Crown (along with Egypt and the Sudan) when Turkey became an enemy. Cyprus exported large amounts of food, fuel and pack animals to the British expeditionary forces in the Dardanelles and Egypt. Products exported for military purposes included oats, barley, wheat, onions, chopped straw, vinegar, bran, potatoes, carobs, raisins, eggs and 40,000 goats, as well as timber and fuel. Over 13,000 Cypriots were recruited by the army as muleteers, which affected domestic food production given the absence of so many men. The Cyprus Military Police force (763 men) conducted anti-espionage work and patrolled the extensive coastline.

Section one of volume two of The Empire at War was entitled ‘The War Effort of the British West Indies’, which documented the contribution of the extensive island empire in this region in terms of ‘men, money, and munitions’, the latter loosely interpreted to capture the supply of commodities such as rum, sugar, cocoa and lime-juice to British forces and the British home front. Niche products supported military production, such as the British Honduran mahogany used to manufacture propellers for airplanes and airships, and Sea Island cotton used to make aeroplane wings and balloons. Trinidad supplied oil for the Royal Navy, and the pre-war slump in agricultural prices was in most cases reversed by the war, to the extent that the value of land rose dramatically, the price of plantations in Barbados, for instance, rising from £30 to £200 per acre. ‘This prosperity was not, however, shared to any great extent by the labouring classes. Wages rose, but the rise was by no means commensurate with the increase in cost of living engendered by increased prices of imported articles.’ In particular, shipping shortages and Germany’s turn to unrestricted submarine warfare ‘demonstrated forcibly’ the dependence of the West Indian territories on imported foodstuffs, which led to the appointment of food commissions and food controllers, as well as measures to increase domestic production. In Barbados, for example, the Vegetable Produce Act of 1917 made it compulsory for landowners to plant a designated acreage with vegetables, corn and roots. With sea communications between Caribbean islands and Britain diminished, along with the import–export business that depended upon them, Canada and the United States were turned to as markets and a source of food and manufactured goods, and American companies began to make inroads into West Indian markets.

War also brought military activity to the region, including defensive measures given the threat of German raiders such as the Dresden and Karlsruhe and enemy landing parties, and the dispatch of troops in support of the imperial war effort. A detachment of the Royal Canadian Garrison Artillery was stationed in St Lucia from 1915 to 1918, alongside French soldiers from Martinique. Heavy guns were mounted in Barbados, St Kitts, St Vincent, the Bahamas and elsewhere, often manned by the Royal Marines Light Infantry and the Royal Marines Artillery. As a precaution against the threat of enemy submarines, the West Indies Motor Launch Flotilla was created, comprising a dozen vessels that patrolled key waterways in places such as the Gulf of Paria. Bermuda was a base for the Royal Navy’s North America and West Indies Squadron, regularly visited by warships, and a coaling port and port of refuge for Allied merchant vessels.

Jamaica was second only to New Zealand in adopting compulsory military service, and was the powerhouse of West Indian military recruitment. Not only did Jamaicans recruited in their home island serve in the military, but they were also drawn from overseas communities, such as the 2,100 Jamaicans recruited from the large number of men working in the Panama Canal Zone. The West India Regiment, originally raised in the 18th century, served in the campaigns against German East and West Africa early in the war, and a new and separate British West Indies Regiment was created, the first contingent arriving in Britain in autumn 1915 for training at Seaford Camp in Sussex. Altogether, 11 battalions were raised for this formation. Elements moved to Egypt early in 1916 for training in Alexandria before deploying to the Canal Zone on defensive duties. Other battalions served in France, carrying heavy shells, in East Africa on lines of communication and in Mesopotamia (including the Honduras Contingent). British West Indies Regiment battalions also saw active service as part of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, distinguishing themselves in the Jordan Valley in 1918 during the advance on Amman. The West Indies contributed a total of about £2 million in cash to the British government, war funds and British charities. Contributions also came in the form of specific items or monies for specific items, such as the nine military aircraft donated by the West Indian colonies and the 300 polished walking-sticks of creole hardwood sent from Trinidad and Tobago for the use of wounded men servicemen in Britain.

Related articles:

Picturing Loss: Families, Photographs and the Great War – Round Table Journal

War Graves in Flanders 1925 – Round Table Journal

The Canadian Experience of the Great War: A Guide to Memoirs – Round Table Journal

The Caribbean’s Great War – West India Committee