From the use of child labour to make clothes to sexual trafficking - parliaments urged to pay attention to everything on their watch. [Source: Walk Free]

From the use of child labour to make clothes to sexual trafficking - parliaments urged to pay attention to everything on their watch. [Source: Walk Free]

The crucial role of parliaments in holding governments to account for human rights, including their commitment to UN conventions and the performance of national human rights institutions, was the theme of a major Commonwealth conference in London from 24 to 26 January. Only around ten Commonwealth parliaments have human rights committees as such, but there were participants from 14 Commonwealth countries, as well as MPs from Serbia, Bosnia, Lebanon, Tunisia and Morocco.

The powers, budgets and interests of these committees varied enormously, but there was a strong push to promote a human rights and rule of law agenda at the 2018 Commonwealth summit in Britain, and at meetings of the Arab League and African Union.

Human rights have been controversial in the inter-governmental Commonwealth, and at some meetings of the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association, but at a time when The Gambia is expected to return to the Commonwealth after the Jammeh regime left in protest at the association’s values, there is a new opportunity.

Patricia Scotland, opening the conference – which took place in Marlborough House and the Houses of Parliament – referred to her own work in combating domestic abuse in the UK. New Commonwealth Secretariat institutions, such as an office for civil and criminal legislative reform, and a unit to challenge violent extremism, could make a difference too. Parliamentarians were vital, and 60 -70% of the recommendations made in the UN’s Universal Periodic Review process actually require legislation. She argued that more can be achieved by consensus than confrontation, and there remain huge needs to protect the rights of women and children.

Tackling national practices

Participants were reminded that the UN is encouraging countries to create national action plans for business and human rights, and they observed a meeting of the UK’s joint committee on human rights which questioned leading retailers, from ASOS, Marks and Spencers, Burberry and Next, on their practices. The British committee wanted to know what efforts these firms are making to guarantee that their suppliers do not use child labour, provide living wages, and do not discriminate against those who join trade unions.

Commonwealth parliamentarians found this was one of the most valuable elements in the conference, and they themselves conducted a model inquiry on the last day into trafficking and modern slavery.

This issue is likely to be pressed at next year’s summit, partly because the British Prime Minister led legislation against modern slavery when Home Secretary, and the involvement of the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative and Commonwealth Parliamentary Association-UK (sponsors of the conference with the Commonwealth Secretariat ).

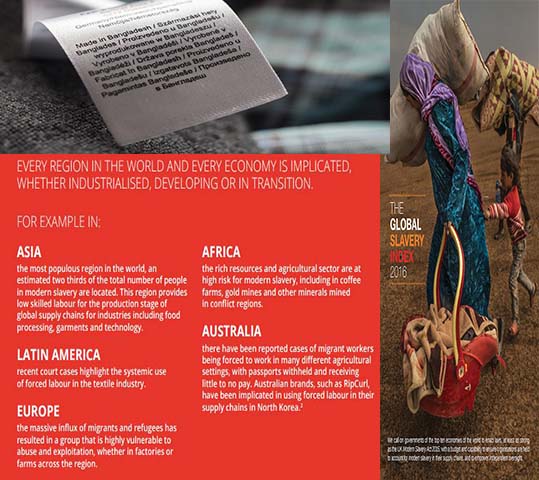

It is estimated that there are 45.8M people in coerced labour, according to the Global Slavery Index available online. They suffer from bonded labour, sexual trafficking and industrial, agricultural and domestic servitude.

Policing to stop modern slavery

A British police superintendent, Paul Griffiths from Gwent in Wales, told the conference that the prevention of modern slavery as well as domestic abuse requires a change in mindset for policing. Whereas police in the past had been focused on public space and public order, they must now deal with crimes in the private sphere.

But progress is being made, as Katharine Bryant of Walk Free told the parliamentarians; a bill in India, designed to help the victims of bonded labour, is now in its eleventh draft and, if enacted, will assist millions of exploited workers.

The 50 participants asked some good questions.

One Ugandan parliamentarian suggested that even the tiniest sum for a trafficked “slave” would be better than total indigence at home. Another MP asked why “modern” slavery – wasn’t slavery just slavery?

At a time when there is a Caricom commission seeking reparations for transatlantic slavery that ceased nearly 200 years ago both questions demonstrated that Commonwealth parliamentarians need to remain vigilant, willing to challenge, and a huge resource for the rule of law and human rights.

[Richard Bourne has worked in the British press, was a special adviser at the Commonwealth Secretariat for the Iwokrama rainforest project, and first Director of the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative. He is currently a member of the Round Table Editorial Board and a Trustee of the Ramphal Institute.]