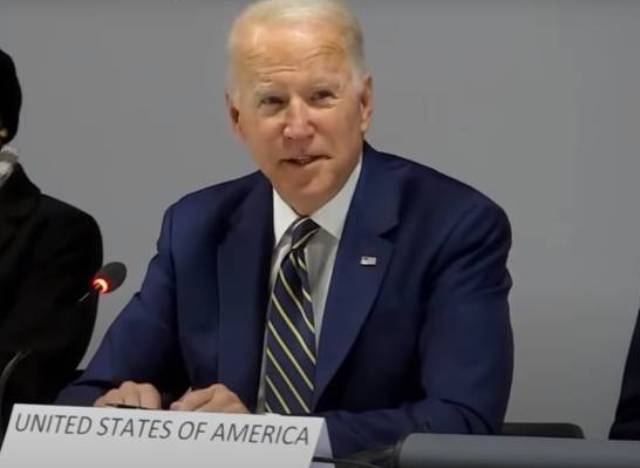

"President Biden’s approach seems to be starkly similar to that of Trump". [photo: President Joe Biden at COP26]

"President Biden’s approach seems to be starkly similar to that of Trump". [photo: President Joe Biden at COP26]

[This is an excerpt from an article in the latest edition of The Round Table: The International Journal of Commonwealth Affairs. Opinions expressed do not reflect the position of the Round Table Editorial Board.]

Firstly, America’s propensity to leave its allies and friends ‘high and dry’ has weakened its ability to forge partnerships that can act as a strong deterrence against China. The decision to almost exclude its allies in the entire withdrawal process can create rifts at a time when it is most important for all to work closely together. From unilaterally deciding the timing to the haphazard ‘no conditions’ withdrawal, President Biden’s approach seems to be starkly similar to that of Trump. Ironically, the Biden administration has painstakingly stressed the need to ‘undo’ the Trump era’s exclusionary policies with regard to allies. Such variance between America and its partners is bound to impact how they will collectively address the China challenge. This will also allow Beijing the perfect opportunity to fill in the leadership and economic vacuum. For instance, New Delhi, despite deep cultural and civilisational links with Afghanistan, continues to be out of the crucial decision-making process, even as it is left to find solutions to a complicated security situation.

Secondly, America’s ill-conceived exit strategy to leave behind $85 billion worth of weapons is bound to hurt its security apparatus, along with its future war preparedness. Given China’s history of successfully reverse engineering weapons technology in the past, it’s unlikely such a large amount of weaponry will stay out of its reach for long. This scenario is even more plausible due to the deep security links China has with Pakistan. Since Islamabad is the benefactor of the Taliban, it is highly likely that the arms left behind by America in haste will reach Chinese weapons manufacturing facilities quite soon. This will allow China to create prototypes to compete with superior US weapons. America’s allies like Japan and Korea and partners like India have varying degrees of compatibility with US weapons platforms. This could be compromised if Beijing is able to use the latest, technologically advanced arms cache in Kabul.

Thirdly, China will build a link from Pakistan to Iran, both by using infrastructure projects and by fanning anti-India sentiments within radical Islamic elements. The expectation is that this will compound security concerns for India, limiting its ability to be a geo-strategic heavyweight against China. If China is able to bog India down on immediate border issues, it will have a bearing on the latter’s potential to act as a pivot against the former’s overreach.

Recent American actions have created chaos and upheaval in India’s backyard. Resolving the present complex situation will require prudent decisions. At one end India will need to boost its military capabilities to deal with volatile border situations. At the other end it will need to be clear-eyed about the security and terror related implications of the China-Pak-Afghan-Iran nexus. New Delhi will also need to reorient its Russia policy to keep pace with the changing geopolitical realities of Moscow and Beijing being now in a tighter security and economic embrace.

For both China and India, along with America, Afghanistan presents both a challenge and an opportunity. The challenge for Xi Jinping is to ensure the Taliban do not become a catalyst for a larger Uighur Muslim movement. For India, a big challenge is to keep American interests in the region alive and active. New Delhi will need to use deft diplomacy to ensure America stays committed to the Indo-Pacific region to check China’s growing appetite to challenge the status quo.

Gaurie Dwivedi is a journalist and author in New Delhi, India.