[This is an excerpt from an article in the current edition of The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs. Opinions expressed in articles do not reflect the editorial position of the Round Table Editorial Board.]

The response of the New Zealand Government to the outbreak and spread of the Covid-19 coronavirus has been categorised as swift and firm. The response began well before the first report of any outbreak in New Zealand.

On 3 February, the New Zealand Government announced that foreign travellers who left from China would be denied entry to New Zealand, with only New Zealand citizens and permanent residents and their family being allowed to enter.

New Zealand confirmed its first case on 28 February, a domestic citizen in her 60s who had recently visited Iran. On the same day, the Government extended the travel restrictions to include travellers coming from Iran. Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern announced that, from 16 March, all travellers arriving in or returning to New Zealand from outside the country must self-isolate for 14 days.

On 16 March, Ardern called for a halt to public gatherings of more than 500 people, and on 19 March, the Government required the cancellation of indoor gatherings of more than 100 people. New Zealand’s borders were closed to all but New Zealand citizens and residents, with few exceptions.

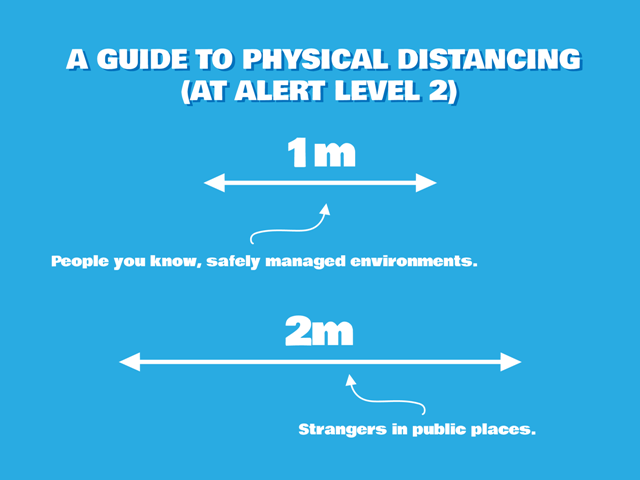

On 21 March Ardern announced the introduction of a country-wide alert level system. New Zealand was initially at level 2 and people over 70 years old and those with compromised immune systems were asked to stay at home. With a rapidly changing situation, on 23 March new cases included two suspected community-spread ones, which led Ardern to declare that the country would enter alert level 3, effective immediately. The closure of all schools began then.

On 25 March a national state of emergency, under the Civil Defence Emergency Management Act 2002, was declared by the Minister of Civil Defence, Peeni Henare. The alert level was raised to four at 11:59 pm on 25 March, instituting a nationwide lockdown. All sports matches and events as well as non-essential services such as pools, bars, cafes, restaurants, playgrounds were required to close within 48 hours, while essential services such as supermarkets, petrol stations, and health services would remain open. In addition, the Government provided a wage subsidy, leave and self-isolation support for those affected by the lockdown.

The decisions to impose travel restrictions from 3 February onwards, and to essentially confine non-essential workers and all others to their homes from 25 March – after a short period of less extreme ‘social distancing’ practices – were widely welcomed. The success of the early and harsh measures was reflected in the low number of deaths and relatively few infections – at least half of which were directly connected with international travel. However, there were concerns expressed about a number of aspects of the Government’s response.

On 31 March epidemiologist Sir David Skegg, appearing before Parliament’s Epidemic Response Committee, criticised a lack of testing, a lack of clear direction and a plan. It was also alleged that much of the Government’s response was not pandemic-related – such as funding for beneficiaries and raising the minimum wage – and that testing and contact-tracing were inadequate. The refusal to quarantine returning citizens (instead using largely un-policed self-isolation) was also criticised. Discussions continued on the possibility of using mobile-phone applications to trace contacts, and thus track potential virus spread, some weeks after a number of other countries had contemplated similar measures. Compulsory quarantine for New Zealanders returning home was announced to commence by the end of the day on 9 April, much later than might have been expected.

Perhaps more significantly, the harsh restrictions, which effectively placed the economy into stasis, showed a strategy which placed greater emphasis on saving lives than on preserving the economy for the post-lockdown period. The hope expressed by the Government was that the harshness of the measures would allow lifting the lockdown sooner, but placing much of the economy on hold meant that there might be more profound long-term economic consequences, especially if a longer lockdown was necessary.

Noel Cox is a Lawyer, Independent Scholar and Anglican Priest in New Zealand.