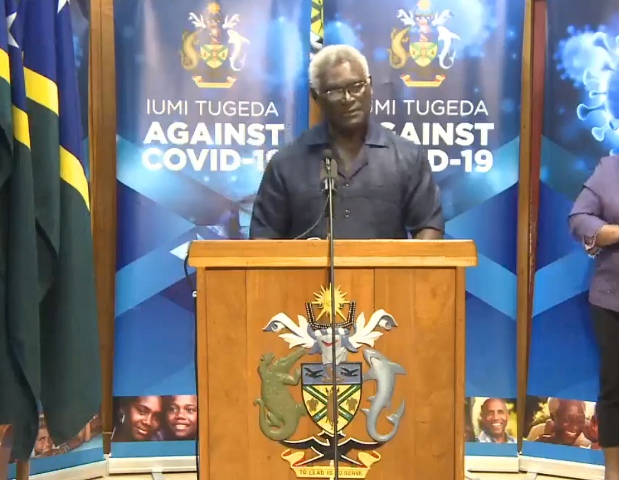

Prime Minister Sogavare "can argue that the agreement with China gives Solomon Islands more options". [photo: Prime Minister's fortnightly briefing, May 2022]

Prime Minister Sogavare "can argue that the agreement with China gives Solomon Islands more options". [photo: Prime Minister's fortnightly briefing, May 2022]

[This is an excerpt from an article in The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs. views expressed do not reflect the position of the Round Table editorial board.]

China’s security agreement with Solomon Islands as signed in April 2022 has caused considerable controversy in Oceania and beyond. Some commentary in Australia went to extremes with calls for an Australian invasion of the Solomons.

At a political level, the recently displaced Australian prime minister Scott Morrison declared a Chinese military base in the Solomons a ‘red line’; his deputy prime minister, Barnaby Joyce, said that Australia could have its ‘own little Cuba’. Such statements highlighted assumptions about the South Pacific as Australia’s ‘backyard’. There was a sense in Australia that Solomon Islands had bitten the hand that fed it, given Australian leadership in RAMSI (Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands, 2003–2017), and security assistance provided more recently following riots in Honiara in November 2021.

One Australian concern in the Pacific Islands region has been increasing Chinese involvement. This was an important rationale for the Pacific ‘step up’ as announced by Morrison in November 2018. China’s more assertive international stance (not just in the Pacific islands), including increased tensions with Australia, heightened Australian concerns. Before 2019 there were suggestions that Australia and China could cooperate on some aid projects. Australia has remained the single most important source of development assistance to the independent Pacific Island countries (PICs), but China (allowing for some fluctuations) is among the major donors.

It is worth recalling that Solomon Islands only switched diplomatic recognition from the Republic of China (Taiwan) to the People’s Republic of China in 2019. The issue of diplomatic recognition is very much bound up with domestic politics in Solomon Islands, with the province (island) of Malaita generally being more sympathetic to Taiwan. In the past, post-election jockeying in Solomon Islands has been subject to financial blandishments from Taiwan; the PRC is in an even stronger position in that respect. The resources needed to have a political impact in a small island developing country of only 700,000 people are not considerable.

From Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare’s perspective there is no doubt a certain ‘thumbing of the nose’ at the ‘neocolonial master’. Gratitude is not necessarily a strong political emotion; resentment can be very powerful. Strategically, Sogavare can argue that the agreement with China gives Solomon Islands more options, reducing dependence on Australia and other Western countries. Fiji has used a similar strategy, particularly during the period of military rule, 2006–2014.

The exact text of the agreement between China and Solomon Islands is unclear. A large-scale ‘base’ is unlikely. Facilities for supporting naval visits appear probable. There is also provision for Chinese security assistance upon request, including the protection of Chinese aid projects and Chinese businesses. While the distance from Cairns in north Queensland to Solomon Islands is only about 1750 kilometres (about 1100 miles), historical analogies referring to the part played by the naval battles for the Coral Sea (May 1942) and for Guadalcanal (November 1942) in resisting Japan’s southward expansion are not very apt for the contemporary context.

A fundamental issue is to respect the sovereignty of Solomon Islands. While the new agreement can be viewed as a strategic setback for Australia and associated powers, the contest for influence in Solomon Islands is a continuing one.

Derek McDougall is a Professorial Fellow, School of Social and Political Sciences at the University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia.