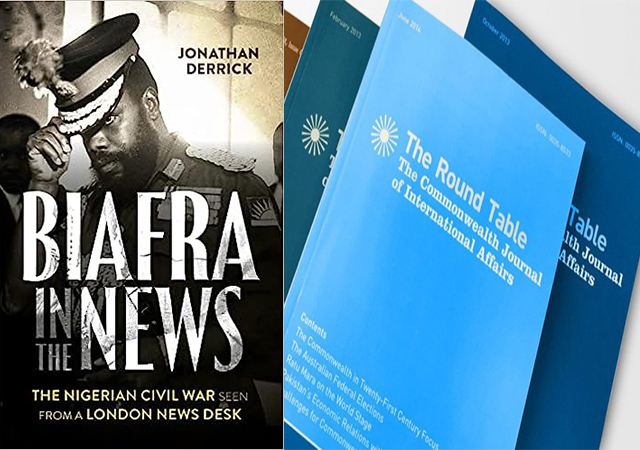

[This book review is from The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs.]

This is an outstanding text for two principal reasons.

First, it is as close as we are likely to get to a comprehensive real-time analogue record of how and why the Biafran tragedy began, developed from its ‘phoney war’ phase and moved to an appalling end, all from the point of view of a Western media organisation’s staff who were covering it for a domestic and an international audience. It is a remarkable blend of vivid reportage and considered historical perspective (as well as – sparingly but bravely – judgement).

And second, Biafra in the News is a window open onto a sharply preserved time-district more than half a century ago. Biafra, after all, is not found on the map today. The book is a window, too, upon a vanished media landscape and an epoch when such reporting differed in important respects from today’s.

The author says at the outset that he never visited the war zone (though he spent time there afterwards). But his front-row-seat, energetic record of the correspondents going to and fro at the time is impressive and evocative.

The latest edition of The Round Table Journal

The Struggle for Modern Nigeria: The Biafran War 1967–1970

Britain and Biafra A Commonwealth civil war

Biafra’s famine victims, those monochrome pictures of the late 1960s, traumatised an entire generation in the West. I speak as a someone who was indelibly marked by them, having been an impressionable 10-year-old when those images reached the British media. The record also shaped the sensibility of a generation as to what ‘disaster journalism’ meant. Circling reluctantly back to the archive as necessary research for this review, I shuddered all over again.

Consider, too, the constraints that journalists in the late 1960s were operating under. ‘This was the age of the telegram and the typewriter; computers were known only as big machines found in a few other offices’, Derrick writes (p. 25).

The connectivity of news in 2023 has its own drawbacks, but the shift to a digital environment has been decisive and transforming. Would today’s digital milieu enable a nucleus of Biafra famine-deniers? Disinformation and fake news were not unknown even then. ‘From January 1968 Biafra employed a public relations firm based in Geneva, Markpress (…) It was a competent outfit, but it was subject to the direction of the Biafran regime (…) that regime was not so media savvy (…) an example (…) came in late January 1968, when it made a wild allegation that a thousand British troops were sailing from Liverpool to reinforce the federal army; this was apparently based on a trip by sea to West Africa arranged by the Commonwealth Institute for 715 British teenage schoolchildren (…) The following May a similar daft allegation was made by the Biafrans: that the Hibernian Football Club then touring Nigeria were in fact British paratroopers’ (pp. 117–118).

Today for the publics of developed West and global North with their fast line-speeds, the report of the war is the war. And the larger news organisations have by a process of retrenchment and media-mergers tended to consolidate and to employ fewer correspondents in the developing nations (or emerging markets, a term less-used in 2023). For all the benefits brought by rapid communications, the pervasive impression is that coverage has become shallower and less consistent.

Another crucial element when considering what was reported from Nigeria in the late 1960s must be the characters of the journalists themselves. They were people working within and sometimes around the agenda of their employers. It is an open question as to whether a journalist working today in the West has the same latitude and freedom of action. But what is certain is that courage was an operative element in the reporting of the Biafran conflict and famine and the Nigerian Civil War throughout. In this connection, the late Kaye Whiteman’s reports for West Africa deserve special mention. His name figures time and again in these pages and his brave involvement helped to form the record.

My appreciation of Biafra in the News is that of a journalist and a former colleague of some people mentioned in the narrative. But Jonathan Derrick’s approachably written work would have an equal appeal to the historian and the general reader.

Martin Mulligan is a member of the Round Table editorial board.

Biafra in the news: the Nigerian Civil War seen from a London news desk by Jonathan Derrick, London, Hurst, 2022.