[This is an excerpt from an article in The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs.]

Amongst the books that have appeared in TRT’s Commonwealth Bookshelf, there are those that have documented the colonial experience and the, often violent, transition to independence. What stands out in the decolonisation of certain, current or former, mainly British colonies, is a remarkably low level of armed conflict and civil strife against colonial rule. Instead, we come across a surprising excess of expressions of allegiance – rather than hostility or resistance – by these colonial subjects. I remember reading about such lingering loyalties to Britain and Empire in the book Outposts by Simon Winchester, which covered all inhabited overseas territories of the United Kingdom; as well as Islandness and Britishness, edited by Jodie Matthews and Daniel Travers (2012), which also considers places like the three Crown Dependencies, Grenada, Heligoland, Jamaica and New Zealand. Two common denominators here are islandness and small size, which together conspire to render the colonial experience a long, deep and intimate one.

Malta falls squarely in this camp. Reconfigured by Britain as a fortress, part of the chain that stretched from Gibraltar through Suez and Aden to India and Singapore to ensure Britain’s command of the seas, the Maltese archipelago – just 316 km2 of land – formally became a British colony with the Treaty of Paris (1814) until its independence in 1964. But this ‘final act’, as Maltese historian Joseph Pirotta puts it, was not reached before an attempt at integrating Malta with Britain. An integration referendum in 1956 secured the required majority of votes (77%); but a ‘low turnout’ (59%) was used as an excuse by the British authorities so as not to honour the result. We Maltese were foolish enough then to believe that Britain would welcome Malta like a second Sussex into its fold.

By Godfrey Baldacchino

Construction as pseudo-development in Malta

Coronavirus and Malta: weathering the storm

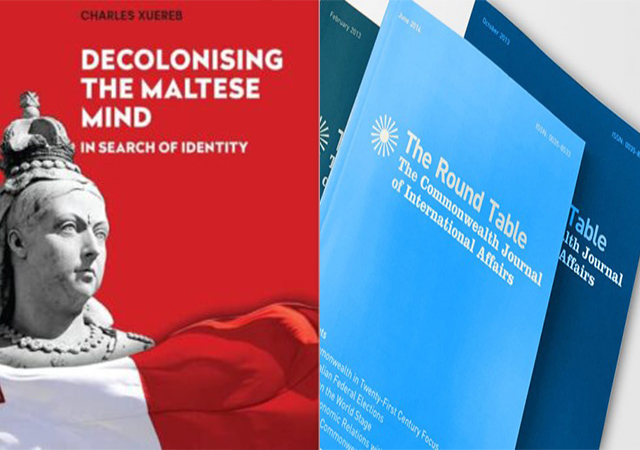

Longstanding media educator and journalist Charles Xuereb has long been a critical voice of Malta’s representations of its own history. It can be expected that a colonial power would undertake initiatives to inculcate a culture of awe, submission and inferiority among its colonial subjects, whereby its Imperial grandeur – personified in its sovereign – becomes then the object of adulation and admiration by the colonised. As Maltese sociologist Edward Zammit explains in A Colonial Inheritance (1984), loyalty was bought by Britain in Malta over the decades by opportunities for employment in the civil service (through English language competence) and by an overall benign and paternalist administration.

Such overtures and manipulative strategies have been strongly resisted across empires by the colonised, with counternarratives of exploitation, subjugation and injustice. For some 40 years after the end of the Second World War, a wave of decolonisation led colonial subjects to canvas aggressively for and secure independence, often involving armed insurrection. Thus was the once planet-straddling British Empire consigned to history, as were other empires (notably, the French, Spanish and Portuguese).

Malta would seem to fit the picture, having obtained its own independence in 1964. But Malta’s independence was not secured after a bout of armed struggle (in contrast with that other British island colony in the Mediterranean, Cyprus) None seems to have been forthcoming, other than riots in June 1919 and April 1958. Otherwise, the subaltern response of choice seems to have been hushed and harmless gossip.

Admittedly, we ditched the British monarch as head of state in 1974. Kingsgate -the main thoroughfare in Valletta, the capital city – was renamed Republic Street. And yet, even almost 60 years after independence, Malta is a work in progress, a sovereign state but not so sovereign on the narratives that drive its interpretation of its history. No wonder we cannot agree to have one national day.

Godfrey Baldacchino is with the University of Malta.