[This is an excerpt from an article in The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs.]

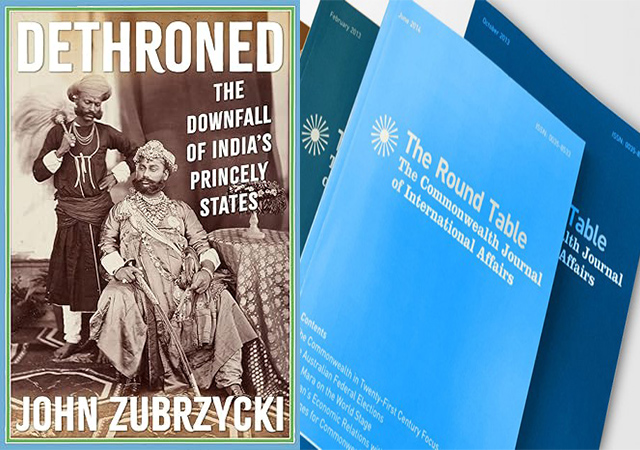

Dethroned – The Downfall of India’s Princely States is an absorbing account of how hundreds of Indian princes were convinced by India’s last Viceroy, Lord Louis Mountbatten, to become part of a free India. Once Britain’s most faithful allies, the princes could choose between joining India or Pakistan, or declaring independence.

The author, John Zubrzycki tells the story of how in July 1947 Mountbatten and two of India’s founding fathers, with strongly contrasting personalities, the country’s most senior civil servant, V.P. Menon, and Congress strongman, Vallabhai Patel, faced an unenviable challenge. They had just three weeks to persuade over 550 sovereign princely states – some tiny, some the size of Britain – to accept the inevitable, exchanging power for guarantees of privileges and titles in perpetuity. But as the back cover of the book states: ‘these dynasties were still led to extinction – not by the sword, but by political expediency – leaving them with little more than fading memories of a glorified past’.

Zubrdycki’s aim is to trace the story of India’s centuries-old princely order, from the arrival of Mountbatten as Viceroy in March 1947 until the abolition of titles, privileges and privy purses in December 1971. He is a master storyteller and writes engagingly and with insight about the princes who played a crucial though perhaps under-appreciated role in shaping the destiny of a democratic India.

Monuments, Power and Poverty in India: From Ashoka to the Raj

Peace, poverty and betrayal: A new history of British India

The range of emotions evoked among the princes by the imminent departure of the Raj is presented with empathy. A handful accepted the inevitability of independence and the necessity of preparing for the new realities it would bring. Many palpably dreaded and resented what they saw as their future once Britain’s political and military protection was withdrawn and feared their hallowed decorations and knighthoods bestowed by the King Emperor in return for their loyalty would be a thing of the past. The remainder had adopted a posture of insouciant denial, carrying on as if nothing was about to change.

Zubrzycki maintains that the princes were badly let down by the departing British who failed to take adequate measures to ensure that guarantees and safeguards were upheld by the new democratic government in India. At the same time he is no apologist for them. He does not hold back on depicting the excesses of the princes who indulged in audacious and frequently obscene displays of pomp and privilege. While India was burning, communal violence was erupting in Punjab and Bengal, Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs were massacred, rajas, maharajas, maharajranas, khans, nawabs seemed oblivious to the butchery which was taking place.

One might think that since so much has been written about the end of the British Raj and the bloodshed that marked the creation of India and Pakistan there is little new to say. The history of this period has been extensively covered by writers like William Dalrymple, Patrick French and others. What this book does is look specifically at how the decision of the princely states to join a new free India might have averted the ‘Balkanisation’ of the country and prevented more carnage.

Dethroned also reviews the personalities, rivalries and prejudices of key figures who were driving the transition to democracy. Patel was the most powerful figure inside the Congress party after the interim Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru. Zubrdycki speculates that if he had achieved his ambition of becoming India’s first prime minister, his centrist pro-market ideology would have seen the country take a radically different course from the socialist model espoused by Nehru.

For Congress leaders, the princely states were bastions of despotism, debauchery and decay. Nehru derided them as ‘sinks of reaction and incompetence and unrestrained autocratic power, sometimes exercised by vicious and degraded individuals’. British administrators and others who had served in these states took a more nuanced view. They recognised that that there were tyrants who should have been deposed had it not been for their usefulness to the British but there were also many states such as Mysore, Baroda and Aundh where indigenous rule was benevolent, devoid of communal friction, based on a stable social structure and carried out in an atmosphere of security and loyalty. While Nehru was making no secret of his abhorrence of feudal autocracy, the father of Hindutva, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, saw the states as representing the true India, ‘portals to a pure, ancient past’, and even as ‘the foundation on which the future nation’ could be launched’.

Rita Payne is a member of the Round Table editorial board.

Dethroned: The downfall of India’s princely states by John Zubrzycki, London, Hurst, 2023.