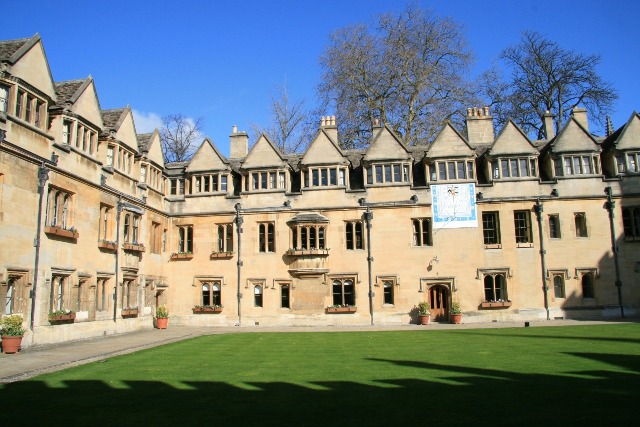

EU sources provide 15–16% of UK research income for UK universities [picture: freegreatpictures.com]

EU sources provide 15–16% of UK research income for UK universities [picture: freegreatpictures.com]

When asked to evaluate the effects of the French Revolution on history, Chairman Mao famously replied that it was too early to tell. Asked to consider the effects of the withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union (‘Brexit’) on Commonwealth universities, less than a year after the historic vote of 23 June 2016, I sympathise.

Even the short-term impact on British higher education remains unclear. UK universities were vocal in their desire for a ‘remain’ vote, and have been sensible in their response, giving as many guarantees to current students and applicants as they reasonably can. The stakes are high. They estimate that EU sources provide 15–16% of UK research income, and that universities account for the bulk of the £730 million EU funds spent on British research and development. Around 125,000 students from other EU countries study in the UK, while British universities employ an estimated 43,000 staff from other EU states.

The future of this funding is all to play for, maintaining it will be the priority. But British universities are robust. They have become increasingly competitive in the last 30 years, and their success has been based more on quality than price. My personal guess is that the UK government will restore at least some of the lost revenue, although not without opportunity cost. Even before the Brexit vote, it had creatively used the overseas development budget to create new initiatives that focus more international development expenditure on UK researchers and scientists. Although important, however, such considerations represent only a small element in the global picture.

The main challenges and opportunities of Brexit are long-term attitudinal, rather than short-term financial. Lost relationships between UK and European researchers will be more important than lost grants, although of course the two are linked. The key question is whether new arrangements will be confined to sustaining existing relationships, or developing new horizons. That question is not just for the UK government, but for those of all Commonwealth countries. Good universities in developing, as well as developed, countries have more international partnership opportunities than they can manage, including EU research and student mobility schemes. The question is not only whether the UK looks to the Commonwealth, but also whether the Commonwealth welcomes an opportunity to strengthen links with the UK.

John Kirkland is the Deputy Secretary-General of the Association of Commonwealth Universities.