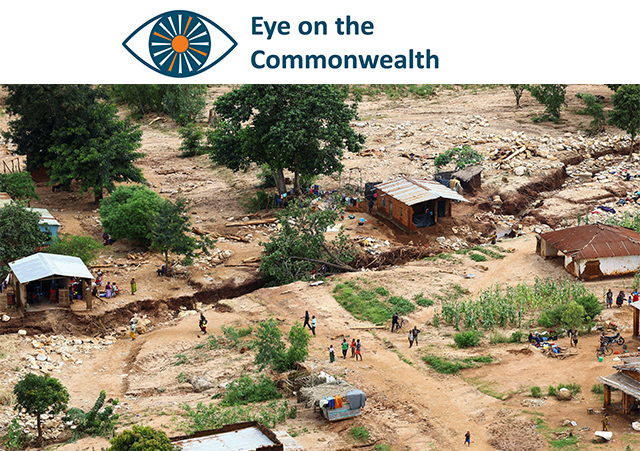

March 2023: An aerial view shows houses damaged in Muloza, outside Blantyre, Malawi, on the border with Mozambique after Tropical Cyclone Freddy. [photo: Reuters/ Alamy/ Esa Alexander]

March 2023: An aerial view shows houses damaged in Muloza, outside Blantyre, Malawi, on the border with Mozambique after Tropical Cyclone Freddy. [photo: Reuters/ Alamy/ Esa Alexander]

Last November, Mozambique’s president, Filipe Jacinto Nyusi, was pictured posing with his energy ministry chefe and other government bigwigs at the inauguration of the Coral-Sul, a ship nearly half a kilometre long that extracts and liquifies gas from the seabed without having to go ashore (where an extremely brutal Islamist insurgency has raged for six years in Cabo Delgado province).

In the background of the photograph were arguably the most powerful people at the ceremony: executives of the Italian energy company ENI, which, with the US behemoth ExxonMobil, is one of the oil multinationals developing Mozambique’s Rovuma basin, a ‘supergiant’ reserve of about 2.4 trillion cubic metres of gas.

Severe storms

Earlier this month, Cyclone Freddy made landfall in northern Mozambique, tearing a 185km-wide swathe across Zambézia province after barrelling across the Indian Ocean at speeds of up to 256km/h (160mph). Lasting for five weeks, meteorologists said it was the longest-lived tropical cyclone ever measured, beating a 29-year record.

Yet this extraordinary weather was only the latest in a series of increasingly severe storms to hit the country. In 2019, Cyclone Idai killed more than 1,500 people in southern Africa; only six weeks later, Cyclone Kenneth also swept through northern Mozambique – the first time that two strong cyclones had made landfall in the country in the same season. Unicef said the devastation left by the cyclones had put nearly 1.3 million children in urgent need of humanitarian aid in Mozambique alone.

There is a quintessential ‘disconnect’ between these two events in Mozambique: the eagerness of governments in the global south to accept the relatively meagre rewards offered by western, Russian and Chinese companies in return for ceding control of their natural resources (ENI proudly talks of training 11 Mozambican engineers and building two primary schools), while the fossil fuels extracted wreak natural disasters on those same impoverished countries.

Guyana: the fast rising Commonwealth petro state. What lies ahead?

Maple Leaf Zeitgeist? Assessing Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s Policy Changes

A “just” transition to green energy: The new Commonwealth challenge

This week, the United Nation’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change issued the last part of its huge report on the climate crisis – a ‘final warning’ about the need to curb greenhouse gas emissions to slow the devastation experienced ever more frequently worldwide. ‘More than a century of burning fossil fuels has resulted in more frequent and more intense extreme weather events that have caused increasingly dangerous impacts on nature and people in every region,’ the IPCC states. ‘Every increment of warming results in rapidly escalating hazards: more intense heatwaves, heavier rainfall and other weather extremes.’

Carbon budget

A key concept of climate science is how much of the ‘carbon budget’ is left before the planet reaches the tipping point of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. A landmark 2019 report for the UN Climate Action Summit warned that CO2 emissions had grown by 2% to a record 37bn tonnes. As burning one cubic metre of gas produces about 1.9kg of CO2, consuming the vast Mozambican gas reserves would pump more than 45bn tonnes of CO2 into the atmosphere. The terrifying reality is that we may have blown the budget even faster than predicted. Amid scientists’ grave warnings, ENI’s boasts of efforts to ‘minimise CO2 emissions’ in exploiting Coral-Sul, while ‘decreasing the energy used to liquefy the gas and minimising the impact on the environment’ seem laughable.

Even the language used around energy can seem absurd. We talk of ‘natural gas’, yet it is methane – a gas nearly 80 times more powerful than CO2 at warming the Earth over 20 years. A Yale study found Americans linked methane with words such as ‘pollution’ and ‘global warming’, whereas natural gas suggested ‘clean’. We also vastly underestimate how much methane comes from fossil fuels, preferring to think of methane as produced naturally by cows or belched from lakes.

‘Eye on the Commonwealth’ columns look at current issues facing the Commonwealth

Fossil fuels must stay in the ground, with production declining globally, if we are to have any chance of keeping within the 1.5°C limit. Even the International Energy Agency, set up in 1974 to secure oil supplies, warned that exploiting new oil and gas reserves must stop, with no new coal-fired power stations built, if net-zero emissions were to be reached. Yet most Commonwealth countries are busily pushing ahead with new fossil fuel projects. The discovery of Guyana’s enormous oil reserves could turn the Amazonian country from a carbon sink to a ‘carbon bomb’; talks on reunification foundered when gas deposits were found in Cyprus’s waters; Nigeria plans to auction seven offshore oil blocks; and even the most progressive of Canadian governments has never flinched from exploiting Alberta’s tar sands, one of the dirtiest sources of fossil fuels.

Climate security or energy security?

‘Those who have contributed least to climate change are being disproportionately affected,’ said one IPCC author, Aditi Mukherji. But as the Ukraine war has shown, the short-term need for energy security can trump governments’ lofty aspirations to address the inequities of climate change. A study released by Shell this week weighs the contrasting goals of climate security or energy security – and sees only hard choices, for which no government has a mandate.

And yet, despite the grim forecasts and escalating graphs, there is still hope of averting the worst-case scenario, according to the report. Hoesung Lee, IPCC chair, said: ‘If we act now, we can still secure a liveable sustainable future for all.’

Oren Gruenbaum is a member of the Round Table editorial board.