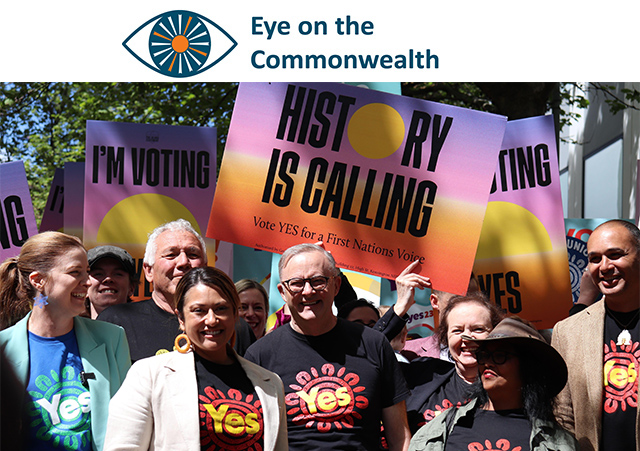

13th Oct, 2023: Prime Minister Anthony Albanese at a 'Yes' campaign event in Hobart a day before the referendum on an Indigenous voice to parliament. [photo: AAP Image/Ethan James]

13th Oct, 2023: Prime Minister Anthony Albanese at a 'Yes' campaign event in Hobart a day before the referendum on an Indigenous voice to parliament. [photo: AAP Image/Ethan James]

The overwhelming defeat was a crushing blow to Indigenous hopes for recognition but many Aboriginal people opposed it too for many reasons

For an organisation born out of an empire, such as the Commonwealth, it is not surprising that many countries have had to negotiate a difficult legacy of inequalities, discrimination and conflict with the Indigenous people of the territory as they emerged from colonies to independence. In Canada, for example, the discovery of more than 1,300 unmarked graves of children at former residential schools is a grim testament to the ‘cultural genocide’ inflicted on its First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples over generations. In India, where minorities of all kinds can be targeted, members of India’s highly marginalised tribes are often lynched.

But the Commonwealth state with arguably the most troubled history with its Indigenous population is Australia. So it seemed a promising step forward when the prime minister, Anthony Albanese, called a referendum over a proposal to give Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders a ‘Voice’ in parliament by recognising them in the constitution.

The result seemed a nailed-on certainty a year ago, according to opinion polls, with two-thirds of Australians supporting the idea. Yet by July it was neck and neck; and in this month’s vote, 60-40 against the proposal. To succeed, the yes campaign needed to win at least four of the six states, and a majority of the national votes, but it became clear long before the vote that it would not reach that threshold. Only in the Australian Capital Territory, the tiny enclave around Canberra, was there a majority in favour. Nonetheless, there was a profound sense of shock at the scale of the defeat.

As with the UK’s bitterly divisive Brexit referendum – which it seemed to echo in its split between older, rural voters and younger, metropolitan ones – there were tears, recriminations and a host of explanations. The pain of having this cherished idea rejected has been far-reaching. Geraldine Hogarth, a Kuwarra Pini Tjalkatarra woman from Western Australia, said: ‘The grief hurts so much, it’s like a knife in your heart.’

An emotional Albanese acknowledged that it was ‘a heavy weight to carry’, especially for Indigenous people who had ‘put their heart and soul into this cause’, sometimes for decades. But, he added, there was ‘a new national awareness of these questions. Let us channel that into a new sense of national purpose to find the answers.’

The challenges of indigenous peoples: The unfinished business of decolonization

Indigenous peoples and climate change: Who pays?

Indigenous Peoples in Commonwealth Countries: The Legacy of the Past and Present-day Struggles for Self-determination

Voice, treaty, truth

The vote had been the culmination of a campaign that crystallised in 2017, when Indigenous elders issued the Uluru Statement from the Heart, which called for ‘voice, treaty and truth’ – a permanent representative forum to advocate to parliament and government, an accord that recognised that Indigenous sovereignty had never been ceded, and a commission to investigate systemic injustices, then and now.

For the 96.2% of Australians who are not Indigenous, initial acceptance gave way to uncertainty as the no campaign – under the canny slogan ‘If you don’t know, vote no’ – chipped away at the ideas underpinning what it called the ‘divisive Voice’, arguing that it would create ‘classes’ of citizens and slow government decision-making.

Led by Jacinta Nampijinpa Price, shadow Indigenous Australians minister, Fair Australia made 10 claims about the proposal, including that it ‘divides us’ (the sixth point was that it also divided Indigenous Australians, unsubtly emphasising the ‘us’ and ‘them’ idea); that it was expensive; that it was ‘a Canberra politician’s Voice’ (echoing the Brexit jibe about remote metropolitan elites); that it undermined democracy; and that it was ‘a platform for radical activists to attack our values’.

For advocates of a yes vote, however, the case was overwhelming. A Senate report on poverty found Indigenous people were nearly three times worse off than non-Indigenous people; half relied on welfare payments; they suffered ill health, disability, infant mortality and severe malnutrition at higher rates. Their children are five times more likely to die by suicide.

For those believing history was irrelevant to present-day inequalities, Guardian Australia insisted: ‘We can’t wish away the shadows of the past.’ It noted that massacres continued until the 1920s, the ‘stolen generations’ (when a third of Indigenous children were taken from their families by the government or church to be brought up as white Australians) persisted until the late 1960s, and the ‘lie of terra nullius’ (no one’s land), remained law until a 1992 court case. Accordingly, even though electorates voting yes were mostly in the inner cities, First Nations communities overwhelmingly voted yes, by three to one in some remote areas.

Crucially, however, several prominent Indigenous Australians came out strongly against the Voice. Price dismissed the idea of any negative effects from colonisation, saying that on the contrary it had a ‘positive impact … now we have running water’. Criticising a ‘grievance before fact’ approach, she said voting yes would ‘demonise colonial settlement in its entirety and nurture a national self-loathing’ and called for a greater focus on domestic violence, abuse, neglect and lack of education in Indigenous communities. While Price’s comments were widely condemned – her government counterpart, Linda Burney, who is also of Aboriginal descent, called her comments ‘a betrayal of so many people’s stories’ – they illustrate the fragmented nature of Indigenous opinion.

‘Eye on the Commonwealth’ columns look at current issues facing the Commonwealth

Find out more about the Commonwealth Round Table and the Round Table Journal

Another Aboriginal politician, the independent senator Lidia Thorpe, attacked the Voice from another angle entirely, damning it as an ‘easy way to fake progress’, a ‘powerless advisory body’, ‘window dressing for constitutional recognition’ and an ‘insult’ to First Nations people’s intelligence. Formerly a leader of the Greens, Thorpe said she now represented the Blak Sovereign Movement, which states: ‘We do not recognise the legality of the colonial constitution and do not want to be a part of it.’

For these radical activists, the referendum lacked any legitimacy: ‘It will be used to demonstrate that we have acquiesced to the colonial system … we have not.’ Rather than a top-down process to create ‘just another powerless advisory body’, the BSM argues that ‘reforms must advance self-determination’ according to the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Anything less, Thorpe said in August, was a ‘destructive distraction, absolving the government of its continued crimes’.

With high-profile Indigenous figures denouncing the Voice, it is unsurprising that doubts set in among Australians initially inclined to vote yes. But conservative opposition parties also played a prime role. The Liberal leader, Peter Dutton, said the proposal would ‘permanently divide us by race’ and would have ‘an Orwellian effect’.

‘Bonkers, mad conspiracies’

Predictions of voter fraud and land grabs spread online and at no-vote rallies. Pauline Hanson, a far-right senator, suggested the Voice could lead to the Northern Territory seceding to become an Aboriginal state. As in the Brexit referendum, the damage from disinformation and outright lies rippled through the electorate faster than the denials and fact-checking. The head of the Australian Electoral Commission dismissed such claims as ‘tinfoil hat-wearing, bonkers, mad conspiracies’ but to little effect. The no campaign’s divisive rhetoric was appealing to ‘racism and stupidity’, said Marcia Langton, an Indigenous academic. For Melora Noah, a Torres Strait Islander, it was simpler: ‘People did not understand it, they didn’t know what they were voting for.’

Before the referendum, a BBC article compared the Indigenous Australian experience with that of New Zealand’s Māori people, and asked why, for all the shared history of dispossession, it was so different. Among the reasons, it suggested, were recognition of the latter’s sovereignty, parliamentary representation as early as 1867, their greater numbers (16.5% of New Zealand’s population to Indigenous Australians’ 3.8%), land title and fishing rights, and 19th-century eugenicist ideas of ‘superior races’.

But most significantly, it concluded, was that New Zealand had been debating notions of reconciliation, representation and reparations since the 1970s, whereas most Australians still had little idea of their country’s history and how it had marginalised and silenced its Indigenous people. That had ‘allowed Australia to proceed with some very comforting myths about itself, in terms of egalitarianism’, according to Prof Mark Kenny, of Australian National University. ‘The atrocities that occurred to the First Peoples of this country have not been properly taken into account by mainstream Australians. And therefore there’s no great kind of urgency or onus to atone for them.’

Oren Gruenbaum is a member of the Round Table editorial board.