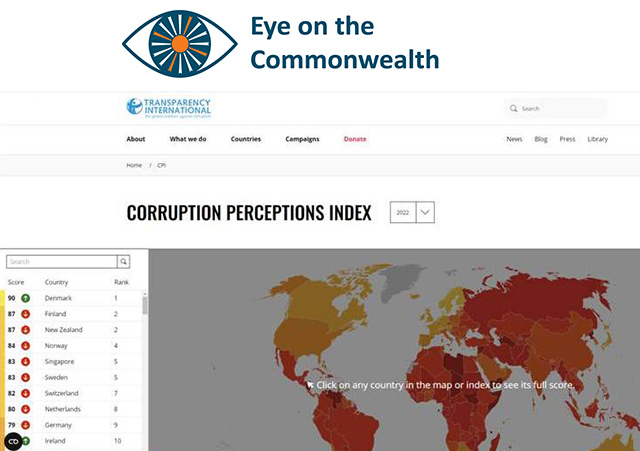

Corruption Perception Index by Transparency International [TI website]

Corruption Perception Index by Transparency International [TI website]

In a message from his prison cell in Russia in 2021, the opposition leader Alexei Navalny suggested that none of the world’s great problems could be tackled without confronting corruption. So news that only one Commonwealth member state is ranked among the world’s 30 worst countries of 180 rated in the annual Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) is perhaps cause for muted celebration. It is Nigeria, again, that wins the Commonwealth’s wooden spoon in the global snapshot of public-sector malfeasance, misfeasance and nonfeasance compiled by Transparency International (TI).

But there is a cluster of other Commonwealth countries following close behind – Bangladesh, Uganda, Mozambique, Cameroon and Pakistan – among the next worst 10. Another four are hot on their heels: Papua New Guinea, Eswatini (the country formerly known as Swaziland), and the Commonwealth’s newest members, Togo and Gabon.

‘Commonwealth principles’

When the secretary-general, Patricia Scotland, welcomed these latter two states, both ruled since the 1960s by father-and-son autocrats, to ‘the Commonwealth family’ last June, she declared herself ‘thrilled to see these vibrant countries … dedicate themselves to the values and aspiration of our Charter’. However, Togo’s president-for-life, Faure Gnassingbé, and his Gabonese peer, Ali Bongo Ondimba, appear to feel that the ‘core Commonwealth principles’ of ‘transparency, accountability, legitimacy’ are more honoured in the breach than the observance, if the case of alleged Togolese/French corruption before a Paris court, the recent conviction of Gabon’s oil chief and the embezzlement charges against four of the late president Omar Bongo’s children are anything to go by.

But the survey is also sobering reading for anyone who might think financial impropriety and lax standards in public office are limited to the world’s banana republics. The UK’s ranking has fallen four places to 18th, with its score dropping five points. It is one of three Commonwealth member states, along with Cyprus and Malta, that had reached ‘historic lows’, according to TI.

The Commonwealth and tackling corruption

Opinion: Corruption allegations in the British Virgin Islands – a sense of déjà vu

Templates for tackling corruption

Tax avoidance

Even New Zealand, the only Commonwealth state apart from Singapore to be regularly in the top 10, has slipped from the No 1 spot. This follows increased scrutiny of the 441,000 trusts registered in the country, which TI describes as ‘opaque’ and claims are often used ‘to hide assets, to avoid overseas tax and to hide ill-gotten funds’.

Singapore also fell, ranking fifth. Only three more Commonwealth states feature in the top 20: Australia, in 13th place; Canada, in 14th; and the UK, with its lowest score in a decade and below Uruguay and Estonia. TI includes the UK, Australia and Canada as being among ‘five traditionally top-scoring countries [that] have seen their assessments decline significantly’. It cited a case last year, an investigation by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project and the Toronto Star, which found that a man implicated in one of China’s biggest military corruption scandals allegedly used Hong Kong-registered shell companies to invest millions in luxury property in Canada.

Pandora Papers

The UK’s image as a well-governed safe haven has drawn wealth, both illicit and legitimately acquired, to London for decades. In recent years, especially under the former prime minister Boris Johnson, the Conservative party’s close links with Russian oligarchs has come under increased scrutiny, particularly when the huge leak of financial records in 2021 known as the Pandora Papers revealed the extent of billionaires’ hidden assets in the UK and its overseas territories.

While acknowledging the UK’s role as ‘one of the leaders when it comes to beneficial ownership transparency’, TI noted that anonymous ownership of properties through offshore companies had remained a ‘key loophole exploited by kleptocrats and oligarchs, with more than 90,000 properties held this way’ and welcomed the government introducing ‘long-awaited reforms’ for greater transparency over these assets after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

‘Eye on the Commonwealth’ columns look at current issues facing the Commonwealth

Zahawi’s taxes

But the issue of transparency continues to dog the Tory government. And as if to emphasise the haze obscuring the affairs of some leading British politicians, Nadhim Zahawi was sacked as chairman of the Conservative party two days before TI’s index was published.

The former chancellor of the Exchequer was fired after an investigation by the new ethics adviser of Rishi Sunak, the prime minister, concluded that Zahawi had broken the rules by repeatedly failing to declare an official investigation into his tax affairs, which concluded with a £5m settlement of overdue tax and a significant penalty for late payment. The tax bill related to the sale of £27m of shares in the YouGov polling firm Zahawi had founded, which were held in the tax haven of Gibraltar and had not been declared by the politician in 2017, when they were first revealed in the press.

Zahawi denied any wrongdoing, saying he made a ‘careless and not deliberate’ error and threatened to sue newspapers for libel if his tax dispute was revealed. However, an investigation by a prominent tax lawyer last year raised the question of whether the then chancellor used an offshore trust to avoid almost £4m of capital gains tax. Zahawi’s affairs were investigated by the tax authorities following a referral from the National Crime Agency.

The ethics adviser, Sir Laurie Magnus, criticised Zahawi for ‘untrue’ public statements over the tax investigation. In his letter dismissing Zahawi, Sunak said he had promised to uphold ‘integrity, professionalism and accountability at every level’. But Zahawi, on leaving office, offered no apology and instead attacked the media for its reporting on him.

Caribbean tax havens

The controversy over contracts awarded by the British government during the pandemic have become well known, such as the PPE scandal around the huge profits made by a Tory peer, Michelle Mone, and her husband. But as one scandal unfolds, the previous one is pushed into the background, such as the Greensill Capital lobbying controversy involving the former British prime minister David Cameron.

Other British cases cited by TI underline the opacity of much of this liminal area where politics meets business. It claims 40 potential breaches of the ministerial code have not been investigated over the past five years, including a cabinet minister and a junior minister approving bids from each other’s constituencies for money from the £3.6bn Towns Fund; accepting £120,000 in donations from property developers while serving as housing secretary; approving a controversial planning application from a Conservative party donor one day before new rules would have increased the developer’s costs by tens of millions; and several meetings with a Chinese state-owned nuclear power company with no record of what was discussed.

It also cites a Sky News investigation, which found some British MPs had declared thousands of pounds in donations from companies where the ultimate source of the funding was unclear and one by Tortoise Media into the expenses-paid trips to the Cayman Islands in the Caribbean by MPs, who then declared their support for the British territory’s administration in fighting measures taken by the UK to close loopholes for tax evasion and financial crime.

‘Largest con in corporate history’

Another country that has barely moved in the CPI rankings in recent years is India, even as its economy has overtaken the UK’s to become the world’s fifth biggest. In 85th place, it is only just in the top half of the index and its score has barely moved in a decade. One reason for this is the continued lack of any legislation criminalising the bribery of foreign officials, despite signing the 2003 UN Convention against Corruption. TI also noted that while protests had pushed through anti-corruption reforms in 2011, the Modi government had imposed an increasingly ruthless crackdown on protest and activists.

More recently, allegations by the US short-selling firm Hindenburg that the sprawling business empire of Gautam Adani, which has a huge share of India’s public infrastructure, has pulled off the ‘largest con in corporate history’, has raised claims of regulatory failings and dubious corporate governance. It has also put a spotlight on Adani’s decades-old links with the prime minister, Narendra Modi, and whether, as the Economist put it, ‘a policy of expediting licences can also slip into favouritism’. Rahul Gandhi, of the opposition Congress party, asked in parliament why the government had not initiated an inquiry into the use of tax havens, saying Modi was ‘trying to protect’ Adani and declaring: ‘This is a matter of national security and India’s infrastructure.’ Referring to an abortive inquiry into Adani in 2021 by India’s markets watchdog and urging greater scrutiny of big businesses, the Economist asked: ‘If a tiny firm of short-sellers in New York can ask hard questions, why didn’t the regulators?’

With so many questions and so few answers in so many countries, it is little surprise that Transparency International concludes: ‘Most of the world continues to fail to fight corruption – 95% of countries have made little to no progress since 2017 … The fight against public-sector corruption has stagnated.’

Oren Gruenbaum is a member of the Round Table Editorial Board.