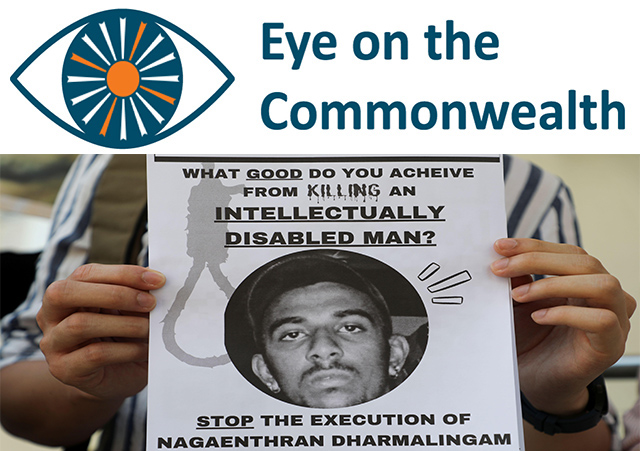

9 March: An activist holds a poster against the execution of Nagaenthran Dharmalingam. [photo: Alamy/ REUTERS/Hasnoor Hussain]

9 March: An activist holds a poster against the execution of Nagaenthran Dharmalingam. [photo: Alamy/ REUTERS/Hasnoor Hussain]

When Nagaenthran Dharmalingam saw his brother on death row the day before he was due to be hanged, the 33-year-old Malaysian apparently had no idea he was facing execution: ‘He talked about coming home and eating home-cooked food with our family. It broke my heart that he seemed to think he was coming home,’ his brother said later.

Dharmalingam was assessed during his trial as having an IQ of 69 – in the lowest 2% of the population.

Navinkumar said his brother had also suffered ‘other delusions’ about taking ‘three-hour baths and sitting in a garden’, adding: ‘He often can’t remember the most basic things and some of what he says is completely incoherent.’

In a cruel twist, Dharmalingam was saved then at the 11th hour, not by an act of clemency or a successful appeal, but by catching Covid-19, leading to his appeal being adjourned and a stay of execution. That was last November. On 27 April, after spending more than a decade on death row, he was hanged – the latest execution in the tiny state, which has long had one of the world’s highest per capita rates of capital punishment.

Dharmalingam was caught crossing from Malaysia to Singapore in 2009 with 43g of heroin – about three tablespoons. Under Singapore’s narcotics laws, among the world’s harshest, anyone caught with more than 15g of the drug faces the death penalty.

According to the campaign group Reprieve, Dharmalingam lived in Johor Bahru, Malaysia, near the Singaporean border. Aged 21 and working as a poorly paid welder, he borrowed 500 ringgit (under £100) to support his father, who was having a heart operation. ‘The man took advantage of Nagen’s desperate circumstances and coerced him into carrying a small package of illegal drugs across the Singaporean border in return for this meagre sum,’ Reprieve said.

The UN Human Rights Council had condemned the death sentence, saying they ‘must not be carried out on persons with serious psychosocial and intellectual disabilities’ and noted that Singapore’s Misuse of Drugs Act had been amended in 2012 to spare those with an ‘abnormality of the mind’. Human Rights Watch (HRW) also stressed that Singapore, as a signatory to the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, was breaking international law by imposing the death penalty on anyone with mental or intellectual disabilities. A petition was signed by 150,000 people and figures such as the business tycoon Richard Branson and the actor Stephen Fry also called for clemency.

Singapore is one of only 10 Commonwealth countries to have executed anyone this century, as most member states either remove capital punishment from the statute books or are abolitionist in practice even if the death penalty has been retained (the others are Bangladesh, Botswana, the Gambia, India, Malaysia, Nigeria, Pakistan, St Kitts and Nevis, and Uganda). However, as the Death Penalty Project points out, Commonwealth states stand out amid a general trend towards abolition: only 37% of Commonwealth countries have abolished the death penalty in law, compared with 57% globally, and half of the 40 countries that voted against a 2016 UN general assembly resolution calling for a moratorium on executions were Commonwealth members.

Reprieve tweeted after Dharmalingam’s execution: ‘His name will go down in history as the victim of a tragic miscarriage of justice. Hanging an intellectually disabled man because he was coerced into carrying less than 3 tablespoons of diamorphine is clearly unjustifiable.’

According to a 2021 HRW report, an IQ of 60-70 is ‘the scholastic equivalent to the third grade’ – a school child aged about nine years old. People with this disability ‘are often ashamed of their own retardation, they may go to great lengths to hide their retardation, fooling those with no expertise in the subject. They may wrap themselves in a ‘cloak of competence’, hiding their disability … Eager to please, people with mental retardation are characteristically highly suggestible.’

This appears to have been the case with Dharmalingam. His lawyers said he was coerced into being a ‘mule’ and carrying the drug after a smuggler in Malaysia threatened violence against him and his girlfriend. However, he later told a court hearing that he had carried the heroin because he needed money. The court concluded that his actions were ‘the working of a criminal mind’.

Dr Ung Eng Khean, a Singaporean psychiatrist, testified that Dharmalingam suffered from ‘an abnormality of mind … severe alcohol use disorder, severe attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), combined type and borderline intellectual functioning/mild intellectual disability’. The judge rejected this evidence.

Another psychiatrist, Dr Kenneth Koh of the Singapore Institute of Mental Health, concluded that while Dharmalingam ‘had no mental illness’ and was ‘not clinically mentally retarded’, nevertheless his ‘borderline intelligence and concurrent cognitive deficits may have contributed toward his misdirected loyalty and poor assessment of the risks in agreeing to carry out the offence’.

Singapore’s Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) insisted Dharmalingam had received a fair trial, adding: ‘Nagaenthran was found to have clearly understood the nature of his acts, and he did not lose his sense of judgment of the rightness or wrongness of what he was doing.’

The appeal court ruled that as Dharmalingam knew it was unlawful to transport drugs, and tried to conceal the bundle by strapping it to his thigh and wearing a large pair of trousers, it showed a ‘deliberate, purposeful and calculated decision’, and ‘the working of a criminal mind’. The MHA said: ‘Nagaenthran considered the risks, balanced it against the reward he had hoped he would get, and decided to take the risk.’

But even the MHA could only say that the high court had found that Dharmalingam ‘was able to plan and organise on simpler terms’ and ‘was relatively adept at living independently’. Hardly the makings of a criminal mastermind then.

Two days before his execution, Dharmalingam’s mother filed an affidavit arguing that her son’s constitutional right to a fair trial had been ‘fundamentally breached’ and there was a ‘reasonable apprehension of bias’ because Sundaresh Menon, the chief justice who presided over the dismissal of her son’s appeal, had been attorney-general when he was convicted.

Not only was this rejected (one judge, Andrew Phang, called it ‘patently devoid of factual and legal merit’) but the attorney-general’s office even threatened Dharmalingam’s mother with contempt of court, declaring: ‘It is the latest attempt to abuse the court’s processes and unjustifiably delay the carrying into effect of the lawful sentence imposed on Nagaenthran.’ One of the arguments used to dismiss the affidavit was that the intellectually disabled Dharmalingam had not raised objections to Menon ruling on his appeal when the point had been put to him in 2016.

For Amnesty International, Dharmalingam’s sentence was a ‘travesty of justice’, and even the most passionate supporter of capital punishment might concede that of the 454 or so prisoners Singapore has put to death since 1991, this case must be one of the flimsiest to pass through its courts.

Oren Gruenbaum is a member of the Round Table Editorial Board.