A 2019 report by Human Rights Watch described

the appalling treatment of thousands of children. [Human Rights Watch website]

A 2019 report by Human Rights Watch described

the appalling treatment of thousands of children. [Human Rights Watch website]

More than 60% of the Commonwealth’s 2.6 billion population are young people so it was to be welcomed that this year’s Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in Kigali decided 2023 would be ‘Year of the Youth’.

In a ‘landmark declaration’, leaders committed to Child Care and Protection Reform, promising to empower young people, boost safeguarding. and tackle ‘root issues that lead to children needing to be put into care’. It also reaffirmed a commitment to the 1989 UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. Signatories pledged to: ‘Implement a policy of zero tolerance for violence, harassment, abuse, stigma, or discrimination, paying particular attention to the most marginalised and excluded children and those in a situation of vulnerability.’

It is regrettable, then, to see such a yawning gulf between Chogm’s high-minded wishlist and the grim reality of life for millions of the Commonwealth’s children, especially those ‘most marginalised and excluded children’ leaders pledged to protect.

When is a Child not a Child and Other Questions – A Commonwealth-wide Overview

A clear and steady voice: The commonwealth human rights initiative at 20

The Commonwealth and human rights

Boko Haram’s hidden victims

Many of Nigeria’s young people, for example, do not have much of a childhood. Nearly 42% of the population are aged under 14, but the UN Children’s Fund estimates that 18.5 million are not in school. Attacks by Boko Haram and other jihadists in the north-east (some 1,500 schools were destroyed by them), armed kidnappers in the north-west, and farmer-pastoralist conflict have compounded problems caused by poverty, early marriage and teenage pregnancies – more than 80% of children drop out of school after 14.

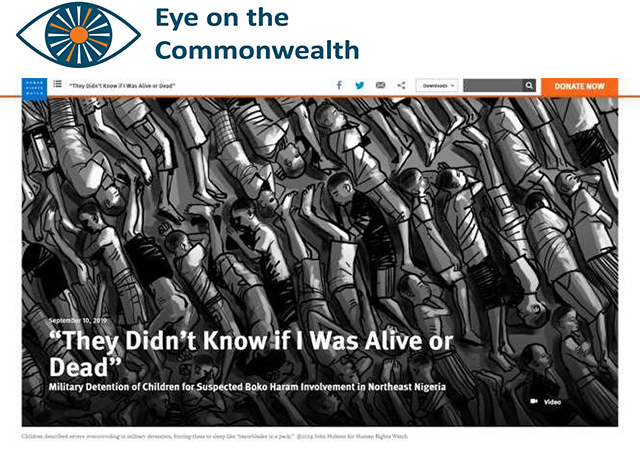

There was some good news this month as the Nigerian government agreed to end the military detention of children, signing a ‘handover protocol’ with the UN that should see children held by the army on suspicion of involvement with Boko Haram transferred within a week to civilian authorities for reintegration into society. In a 2019 report, Human Rights Watch described Nigerian security forces’ appalling treatment of thousands of children, some as young as five, for suspected links to Boko Haram, though most said they had nothing to do with the militants and those that did had been abducted.

Some children were imprisoned for years; few were ever charged with any crime. One boy said he had been held for more than two years for allegedly selling yams to Boko Haram members. So it was cheering to hear that 4,204 boys and girls had been released by the military by September. However, an African Union report estimated that there were 6,000 children in Nigerian prisons as of last December. And children can still be sentenced to death, especially under the northern states’ sharia penal code, so there is still some way to go.

Sadly, Nigeria is far from the only Commonwealth country to lock up its most vulnerable citizens. Australia had 4,695 young people under youth justice supervision in 2020-21, of whom one in six, about 800, were locked up. Most were awaiting sentencing and living in the community, which sounds eminently reasonable.

Discovery of children’s graves a haunting reminder of Canada’s ‘cultural genocide’

The education system in India: promises to keep

The new ‘Stolen Generations’

But of those children being detained nearly half were Indigenous Australians; they make up only 5.8% of Australia’s 10-17-year-olds but 49% of all young people in detention. It is a statistic that seems to belong to the days of the Stolen Generations – the colonial-era policy of forcibly removing Aborginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their parents, which continued until the 1970s.

Indigenous children are also more likely to be sucked into the criminal justice system at a younger age, with a third of them first detained between 10 and 13, compared with 14% of their non‑Indigenous counterparts. In the Northern Territory, young Indigenous people are imprisoned at 43 times the rate of non-Indigenous children. The Raise the Age campaign was launched in 2020 to raise the age of criminal responsibility from 10 to at least 14.

Bailed in Bangladesh

In Bangladesh, the Covid-19 pandemic brought some good news in its wake as 343 children were released from custody in just seven days. Writing for Penal Reform International, Justice Imman Ali, a supreme court judge, explained how prisons were emptied of those on remand with a phenomenal 33,287 bail applications heard and 20,938 people released. ‘We also looked to decongest the Child Development Centres, which held nearly double the number of children that their occupancy rate allowed for – in the three development centres with a capacity of 600 only, 1,140 children were held, mostly in pre-trial detention,’ he wrote. Using virtual hearings, 343 children were released. In Mozambique nearly 1,700 children and young people were freed from detention as part of a similar amnesty to combat Covid.

Criminalising children

By contrast, the UK’s criminal justice system lurched in the opposite direction, with young offenders kept in solitary confinement even as lockdown strictures were relaxed in wider society. A report found young people aged 12 to 17 in what amounted to solitary confinement in their cells for up to 23.5 hours a day.

According to Chris Daw, a criminal defence lawyer, the British legal system is steadily moving in the same direction as the United States, where mandatory custodial sentences are commonplace for children, and some are locked up for the rest of their lives. In his book Justice on Trial, Daw notes that the number of children imprisoned each year rose 500% between 1965 and 1980. But, as he says, ‘criminalising children causes more crime and more victims – and locking children up even more so.’

In 1629, John Dean, an English boy was accused of setting fire to two barns in Windsor. He was tried and found guilty in one day – and hanged, aged eight or nine. The age of criminal responsibility in England then was seven. Four centuries later, the age has only been raised to 10. And, according to the National Audit Office, the number of children in custody is expected to more than double by 2024. The UK might not hang its children any more but it is still remarkably relaxed about locking them up and, in all likelihood, consigning them to a life going in and out of prison, on the margins of society.

Oren Gruenbaum is a member of the Round Table Editorial Board.

‘Eye on the Commonwealth’ columns look at current issues facing the Commonwealth