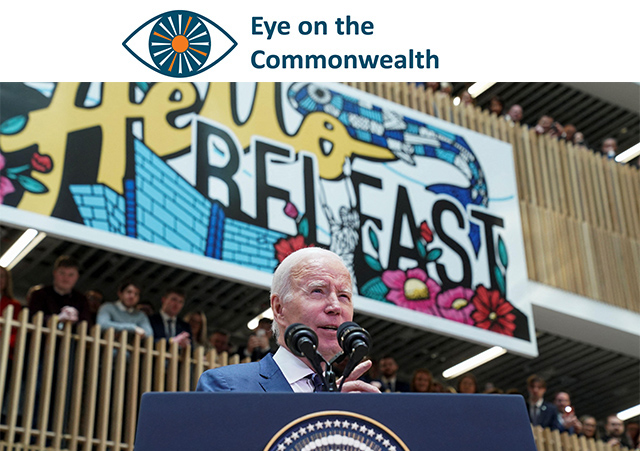

April, 2023: Joe Biden speaks following the 25th anniversary of the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement, at Ulster University, Belfast, Northern Ireland. [photo: REUTERS/Kevin Lamarque via Alamy]

April, 2023: Joe Biden speaks following the 25th anniversary of the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement, at Ulster University, Belfast, Northern Ireland. [photo: REUTERS/Kevin Lamarque via Alamy]

More than a year into the continent’s biggest conflict since the second world war, most Europeans still take peace for granted. This seems particularly short-sighted in Northern Ireland, where over the three decades to 1998 more than 3,600 people were killed and nearly 50,000 injured in the brutal conflict between republicans, who wanted a united Ireland, and unionists, who supported British rule.

Peace is fragile and hard to remake once broken. This Easter, most of the north of Ireland was celebrating the quarter-century since the drawn-out peace process, culminating in the Good Friday Agreement (GFA), ended ‘the Troubles’, as the war in the restless six counties that make up the statelet was euphemistically known. Yet the historic accord between the British and Irish governments and eight political parties from Northern Ireland, brokered by the US senator George Mitchell, has never looked more precarious.

Squaring the Brexit circle

The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) failed to stop the peace talks when they walked out over nationalists’ inclusion in 1997, but they did bring down the delicate power-sharing arrangement last year by vetoing the election of a Northern Ireland Assembly speaker. The ardently pro-Brexit DUP demanded that the UK’s tortuously negotiated trade protocol with the EU be scrapped as it in effect created a border in the Irish Sea.

What they wanted, however, was to square the circle: to have Brexit – with its exclusion from the single market and customs union, and hence border controls with Ireland – but without the ‘hard border’ of checkpoints that were dismantled as a key to the peace deal.

Northern Ireland and partition – Round Table Journal, 1934

Northern Ireland – Round Table Journal, 1952

Book Review – The idea of the union: Great Britain and Northern Ireland, 2022

United Ireland

Intransigence has long been the defining feature of the DUP, which eclipsed the once-dominant Ulster Unionist Party by boycotting the peace talks and then waiting for cracks to appear in the power-sharing edifice, which in the end they brought down. But last year the republican Sinn Féin became the largest party in the assembly, partly due to demographic shifts and the erosion of old loyalties, but mostly because moderate Protestant unionists no longer feared their Catholic republican neighbours and voted across sectarian lines for the centrist Alliance Party and moderate nationalist Social Democratic and Labour Party.

The idea of a united Ireland was no longer anathema, as it had been for their parents. And this was in large part due to the integrating effects of being in the European Union for a generation, of looking as much to Ireland and the EU as to Britain. Unlike England and Wales, Northern Ireland voted to remain in the EU in the 2016 referendum.

A poll in 2021 found that for the first time fewer than half of respondents wanted to remain part of the UK, with nearly two-thirds believing that a united Ireland had become more likely since Brexit (a rise of five percentage points in a year). The Good Friday Agreement allows for reunification if consent is given in both the north and south of Ireland. A poll last year suggests a majority for unification may be only 15 years away. (Republicans might argue, of course, that uniting Ireland is not secession but merely untying itself from an unfair constitutional arrangement forced on it by the British government in 1921).

‘How to end union’

With Ireland being the first non-contiguous country colonised by the English, pressures for independence/secession have been felt for centuries but similar tensions span the Commonwealth. The anglophone regional conflict in Cameroon has grown over a few years from tensions over language into a full-blown civil war, with thousands dead and 500,000 displaced. With efforts at international mediation and the government’s forced reintegration patently failing, secessionist pressures are building.

For the US-based writer and activist Dibussi Tande, the Cameroon government has ‘accommodated neither the radical demands of independentists nor the comparatively moderate demands of the federalists’. For the growing numbers who see a return to the federal system that existed until 1972 as no longer feasible, negotiations must be ‘about how to end the union and not about whether the union should continue’.

In Canada, the secessionist tendencies of French-speaking Quebec have sparked repeated constitutional crises. But more recently the political and cultural polarisation seen during the 2019 elections – between a perceived Ottawa-Toronto-Montreal consensus and the prairie provinces of Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba – spurred ideas of a midwestern secession. The founder of Wexit Canada (now the Maverick Party) talked of excising the ‘parasite of eastern Canada’ and threatened that anyone who stood in the way of ‘Alberta self-determination – you’re our enemy and we’re going to run you over.’

‘Westralia’

A secessionist movement in ‘Westralia’ emerged in 1905 (in step with the discovery of gold in Western Australia, not so coincidentally) and peaked in 1933 as the Dominion League won a referendum on the state’s autonomy from Canberra, with a two-to-one vote for leaving the federation (London’s reaction was largely one of indifference). But resentments can persist, and in 2020 a poll found more than one in four Western Australians still wanted to become independent.

After a row last year over election spending promises, the deputy mayor of Melbourne suggested that Victoria state should pursue ‘Vexit’ and leave the federation as well. And even secession-minded territories can face breakaway tendencies: Western Australia had a 50-year standoff with the self-declared micro-state of Hutt River after ‘Prince’ Leonard Casley declared his farm to be an independent principality in a dispute over wheat quotas in 1970.

The common theme of all of the Australian and Canadian secessionist movements is financial grievances, which can quickly drive a wedge between rural and metropolitan Canadians, or east and west Australia. The harms of globalisation have been much picked over since the 2007-08 crash, but the benefits of cultural connections and commerce are forgotten – they are centripetal forces that bind people and states together.

Though discussing how economic relations acted as a counterweight to US-China geopolitical tensions, the comments in Foreign Policy of Eswar Prasad, a trade policy professor at Cornell University, are equally true of how the EU helped to bind the UK to its neighbours in positive ways – improving relationships between northern and southern Ireland, nationalists and unionists, Catholics and Protestants. ‘Globalisation is not dead, but it has clearly taken a turn toward fragmentation along geopolitical lines,’ he wrote. ‘As economic flows come to closely parallel geopolitical alignments, an important counterweight to geopolitical frictions is being eroded.’

And is the Commonwealth ‘a plausible substitute for the EU?’ asked the Economist in 2018. ‘No,’ was its bald answer.

Oren Gruenbaum is a member of the Round Table editorial board.

‘Eye on the Commonwealth’ columns look at current issues facing the Commonwealth

Find out more about the Commonwealth Round Table and the Round Table Journal