International Press Institute report for World Press Freedom Day 2021 calls for collective action. [IPI website]

International Press Institute report for World Press Freedom Day 2021 calls for collective action. [IPI website]

It says much about the flourishing state of Namibia’s media, in a continent where journalists are often on the defensive, that the country is again ranked the best in Africa, and 24th in the world, in this year’s World Press Freedom Index, compiled by Reporters Without Borders – higher than the UK, France, USA, Australia and Japan. ‘Press freedom has a firm hold in Namibia,’ RSF said, ‘It is protected by the constitution and is often defended by the courts when under attack from other quarters within the state or by vested interests.’

In April 1991, barely a year after Namibia’s independence, journalists from across Africa met in the capital, Windhoek, for a conference sponsored by the United Nations’ cultural body, Unesco, on ‘promoting an independent and pluralistic African media’. The Windhoek Declaration that emerged on 3 May – now commemorated as World Press Freedom Day – was adopted by the UN two years later and emulated by journalists across the world. It emphasised the vital role for democracy of a free press and freedom of expression, and condemned the imprisonment and killing of journalists for doing their job.

‘Today,’ it said, ‘at least 17 journalists, editors or publishers are in African prisons, and 48 African journalists were killed in the exercise of their profession between 1969 and 1990.’ Sadly, nearly 2,000 journalists have been killed around the world in the 30 years since then, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists, and the fight against censorship and disinformation seems as urgent now as it did three decades ago.

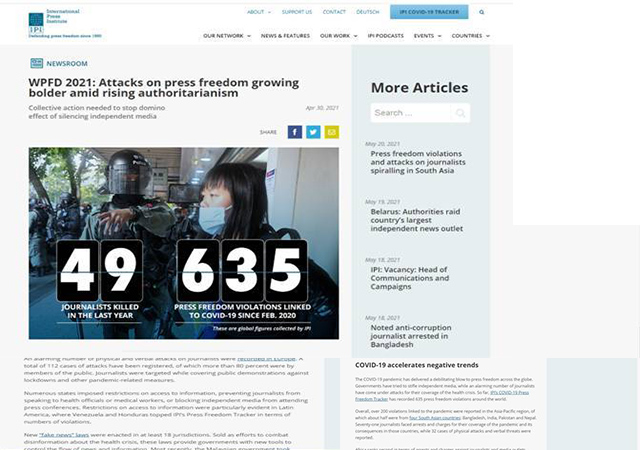

The 2021 Index data, said RSF, reflected ‘a dramatic deterioration in people’s access to information and an increase in obstacles to news coverage. The coronavirus pandemic has been used as grounds to block journalists’ access to information sources and reporting in the field.’ The International Press Institute counted 635 press freedom violations globally since February 2020, as the coronavirus pandemic fuelled authoritarian regimes’ efforts to restrict reporting. ‘Authorities have blocked access to information, arrested journalists for their coverage of the virus, and passed sweeping “fake news” laws that can be used to silence criticism,’ the IPI said, noting that India, with 84 violations, was the world’s worst offender. The institute’s ‘death watch’ programme has counted 14 journalists killed so far this year – and an average of 82 every year since 1997.

While Namibia has long been an exemplar of press freedom, that cannot be said of much of the Commonwealth. Seven member states are among the bottom 40 countries in 180 ranked by the RSF.

Lowest among Commonwealth members, in 160th place, is Singapore, which the RSF classified as ‘very bad’ and has not ranked higher than 149th since 2013. Noting how the state routinely sues journalists critical of the government, makes them unemployable or forces them into exile, it concludes: ‘Despite the “Switzerland of the East” label often used in government propaganda, the city-state does not fall far short of China when it comes to suppressing media freedom.’ Singapore’s Infocomm Media Development Authority calls itself a ‘trusted steward of public values’. However, RSF points out, it can ‘censor all forms of journalistic content’, defamation suits are common and it uses sedition laws largely inherited from the British empire to suppress content. All print and broadcast media are controlled by two companies, one owned by the state and the other run by government appointees. An ‘anti-fake news law’, introduced last year, further restricts free expression by enabling the government to prosecute critics and shut down social media platforms, according to Human Rights Watch, which said: ‘Behind Singapore’s gleaming façade of modernity is a government wholly intolerant of peaceful protest.’

The second-lowest ranked Commonwealth state is Rwanda, up five places since 2013 but still ranked 156th. Eight journalists have either been killed or disappeared, while 35 others have fled abroad since 1996. In March, Dieudonné Niyonsenga, a journalist with Ishema TV, and Fidèle Komezusenge, a driver with the channel, were acquitted and released from prison after they were arrested in April 2020 for allegedly breaching lockdown orders. ‘They never should have been arrested in the first place, and it is a grave injustice that courts entertained a baseless case against them for nearly a year,’ said the CPJ. ‘Legislation is very oppressive and the spectre of the 1994 genocide is still used to brand media critical of the government as “divisionist”,’ notes RSF. ‘Censorship is ubiquitous and self-censorship is widely used to avoid running afoul of the regime.’

In 154th place is Brunei, which has plummeted by 37 places in seven years. With all broadcasting controlled by the state – in effect the sultan – and all leading newspapers owned by his family, self-censorship is usually enough to spare any need for more formal intervention. For when it is not, a sedition law makes any criticism of the ‘national philosophy’ (Islam as the state religion, monarchy as the only type of government, and the privileges of those of Brunei Malay ethnicity paramount) punishable by three years in prison and ‘malicious’ blogging by five years. The imposition of sharia law two years ago (see Commonwealth Update, May 2019) added blasphemy to the list of repressive media laws.

The Commonwealth’s four south Asian member states are clustered within 25 places. Ranked 152nd is Bangladesh, where the correspondent Abu Tayeb, convicted under the draconian Digital Security Act, has joined at least six other journalists in jail; the cartoonist Kabir Kishore said in March he was tortured; and the writer Mushtaq Ahmed died in jail in February. In 145th place is Pakistan, which saw Absar Alam wounded in April and Ajay Lalwani shot dead a month before – the latest of 61 journalists killed since 1992. India ranks barely any higher at 142nd; four journalists were killed last year; ‘sedition’ is still punishable by life imprisonment; and those who dissent from the ruling BJP’s right-wing Hindutva nationalism can find themselves targeted by an online mob, as happened to the cartoonist Rachita Taneja, who faces six months’ jail for lampooning the supreme court. In Sri Lanka, ranked 127th, at least 44 media workers have been killed or ‘disappeared’ in the past two decades.

The worst in Africa are Eswatini (the absolute monarchy formerly called Swaziland, from where editors of two news sites fled last year after publishing articles critical of the status quo, one of them allegedly tortured), and Cameroon (which RSF says is ‘now one of Africa’s most dangerous countries for journalists’ and where the former head of the state broadcaster has been held in ‘preventative detention’ since 2016).

At the other end of the Commonwealth scale is Jamaica, in 7th place, which RSF called ‘almost flawless’ for its ‘widespread respect for freedom of information’ and being ‘among the safest countries in the world for journalists’. In stark contrast to the horrors inflicted on journalists elsewhere, RSF’s only criticism was a 2019 speech by the prime minister, Andrew Holness, in which he mildly observed that having a free media meant some journalism ‘doesn’t have to be the truth [because] it is their opinion’.

According to RSF, just 12 of 180 countries it studied have a ‘favourable environment for journalism’ and apart from Jamaica, New Zealand, in 8th place, is the only Commonwealth state among them. The ‘free flow of information … through a free and responsible media’ is one of the tenets enshrined in the Commonwealth Charter. But despite the best efforts of brave and committed journalists, supported by organisations such as the Commonwealth Journalists’ Association, to hold member states to this principle, many governments appear all too willing to look the other way when one of their peers tramples on free expression.