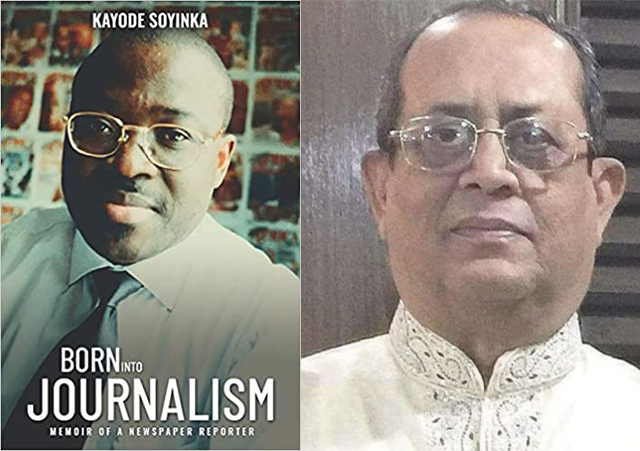

Kayode Soyinka and Hassan Shahriar

Kayode Soyinka and Hassan Shahriar

[This article is from The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs.]

Global pandemics are good news for memoirists, diarists and publishers. World-historical crises concentrate the mind wonderfully on Last Things and put a frame around the life-journeys we have taken. Pandemics also provide leisure for the pursuit of insight; an unexpected side effect of enforced idleness. Readers everywhere can expect a steady supply of such material for some time yet.

Two recent additions to the genre by lifelong journalists and editors are especially noteworthy. These are eyewitness records of a vanished or fast-vanishing epoch: the Analogue Era of journalism, when print and paper were the dominant channels of communication worldwide. The memoirs highlight how we now have one Earth but four or five different worlds, running at different speeds. For instance, as I write, it is reported by BBC Radio Four News that only 1% of vaccines worldwide have reached low-income countries.

Kayode Soyinka’s life story illustrates vividly how all now inhabit closely interwoven distinct worlds. He is a Nigerian journalist famous for being as much a news-maker as a newsman. He survived a parcel-bomb attack that killed Dele Giwa of NewsWatch, his close colleague and friend, at the latter’s Lagos home on 19 October 1986, while Soyinka was visiting the senior journalist. Only a heavy table part-shielding Soyinka from the blast spared his own life. Contrast this with a journalist’s daily reality in the UK. The keenest risk run by such a reporter is that he or she will find himself or herself summoned to a breakfast meeting with a man in a grey suit who will convey a coded message about career prospects.

A broad outline of Soyinka’s career in journalism and then as founder-publisher of Africa Today can be quickly drawn. His was the typical Analogue Era career path: he worked for a local newspaper, then a national one and finally for international newspapers and magazines for 17 years, as a London-based foreign correspondent. Along the way he picked up an MA in International Journalism.

His early career was in a Nigeria only recently independent. He was among the first generation of journalists of that epoch. As a result, his life story as a working journalist – later as a founder-publisher – spans pre-modern, modern and post-modern professional environments. Some of the implications of that we will come to. But it is worth noting at once that there can hardly have been a more exciting and stimulating time to practice journalism in Nigeria and the UK and internationally and that this awareness lends a special vibrancy to his account.

He began as a cub reporter walking the dusty streets of Ibadan looking for stories. He is frank about the low status the profession had then in West Africa, where it was perceived as the redoubt of school dropouts. His memoir serves up a rich platter of anecdotes about his various employers and politicians in the UK and Nigeria, from the late 1970s up to pretty much the present day. Chapter 12 reprints in full his groundbreaking interview with Nelson Mandela: a scoop of sufficient weight to launch Soyinka’s own international newsmagazine Africa Today in May 1995 (when Soyinka was 37).

In Kayode Soyinka’s former professional environment in Nigeria (or that of Hassan Shahriar in Bangladesh), the risks of the daily round may be life-threatening. And this persistent threat to life and limb remains the case throughout much of the Commonwealth, that loose assembly of leading edge and bleeding edge countries.

To work as a journalist in much of the global South is still to take a stand against the forces of strong randomness in daily life. These range from freelance police roadblocks to slow line speeds and lack of resources of all kinds. A situation in which the average African citizen may use the internet as the average citizen of the UK uses it today is still at least a generation away – and perhaps much longer.

We do well to keep this in mind when reading these despatches from the bleeding edge, especially when we happen to be situated in one of the spectators’ boxes of the G7 nations. These are memoirs by journalists for whom the profession was, and remains, vocational, a true calling. They have more skin in the game than the rest of us.

Their writings are also a salutary reminder that scarcity and struggle insulate people from a certain kind of decadence. There is no hint, anywhere, of apathy or complacent self-congratulation in these pages, only an unrelenting dynamism. At its highest pitch, this resembles Dale Carnegie’s self-hypnotism. Kayode Soyinka really was the journalist most likely to succeed.

Born Into Journalism has more than a hint about it of Advertisements For Myself (even the author’s boyhood scouting accomplishments and several Akelas are recorded!). But such content is conventional in this Maileresque genre and can almost be attributed to the demands of the form.

The author’s unselfconscious Christian faith and reiterated gratitude for a stable supportive family background punctuate and shape his narrative. It is clear that he has courageously followed a vocation in journalism, literally his calling.

Soyinka’s memoir is also interesting for what it looks straight past.

Born Into Journalism: Memoir of a Newspaper Reporter is written and published at a moment when comparable UK-centred professional memoirs put the digital tech boom and global financial crises and China’s rise at centre stage. These rival developed-world memoirs are loud with hints and self-compliments about how their authors anticipated the financial crisis even while they were busy turning newspapers into multi-channel global news organisations.

Soyinka’s memoir, in sharp contrast, contains little about the rapid communications revolution that has transformed news media (gradually, then suddenly – as Hemingway described the process of going broke) in the developed world during the last 30 years. That is not because his newsmagazine Africa Today lacks a web presence.

Soyinka is right instead to look straight past this in his memoir because there is an afterlife for print – that is, for so-called ‘legacy media’ – in the global South, especially in Africa and Asia. How long this state of affairs may persist is an open question. But Soyinka’s memoir is, on top of everything else, an important corrective and salutary reminder of a three-speed world.

At the heart of Born Into Journalism is the parcel bombing, a vivid image of the sometimes fatal price paid by journalists brave enough to practise in developing societies. Risks to journalists in Africa and South East Asia still massively outweigh those for journalists in the so-called developed nations.

This theme is also taken up by another memoir, this one by an outstanding journalist from Bangladesh, who also had an international impact.

Hassan Shahriar Living Legend in Journalism is a tribute to a long career that comprises contributions by colleagues and friends made during a very active life. I have to declare an interest in that I wrote one of them.

Shahriar’s career was instructive in several senses. It demonstrated, not least, the important role that Commonwealth organisations and NGOs in the developed world played for a long time in helping to form journalists in other, often poorer, members of the Commonwealth. This was, in retrospect, a golden age of properly funded mentoring. Hassan Shahriar became an international president emeritus at the Commonwealth Journalists Association conference in Malta in 2012, the crowning achievement (of which he was intensely proud) recognising his long service to that body. Soyinka similarly draws attention in his memoir to his own association with the CJA and to important early material help he received from the Commonwealth Press Union.

The funding for such bodies during 30 years has dwindled to the point at which they have become largely email groups. This tracks an ideological policy shift from about 1995 when journalists in poorer countries were still seen as ‘a voice for the voiceless’; through a period of expanding emerging markets when they were ‘the conscience of the corporate world’; to today’s pervasive aid-fatigue, which requires any project to pass through a fine mesh of ‘quantifiable returns on investment’.

But, in the meantime, the problems facing journalists in these places have not gone away. Murray Burt, veteran Canadian journalist and President Emeritus of the Commonwealth Journalists Association (CJA), writes:

In much of our Commonwealth (and its) journalistic communities … lies, intimidation, threats, even brutality, death and dictatorships all can be part of a day’s experience and headlines in too many of our 52-nation members.

Hassan lived and worked much closer to these not-so-sweet societies than I did. Southeast Asian Commonwealth nations are far tougher to report in than the conditions we enjoy in New Zealand, Australia, Britain and Canada. A level of toughness is too often present everywhere, but Hassan and his colleagues’ playground is too often brutal not only at the street and home level but also in government where spilled blood and death are too often part of (or the end of) an assignment. (From the chapter CJA Gave Me Finest Friends by Murray Burt, p. 58).

Martin Mulligan is a member of the Round Table Editorial Board.