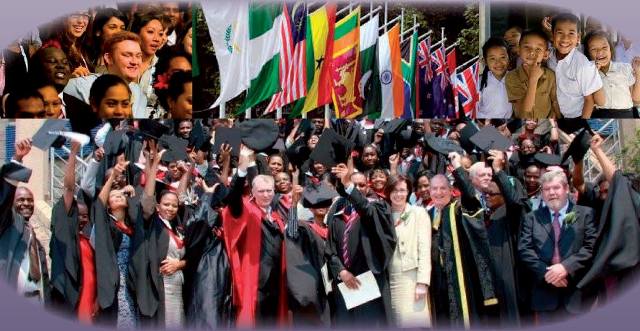

The Council for Education in the Commonwealth explores the global educational challenges of the 21st Century

The Council for Education in the Commonwealth explores the global educational challenges of the 21st Century

If robots are taking over most of our jobs and the plan is for most people to have a life expectancy of 100 years, what are we all going to be doing with this extra time?

This might be a moot point for a person in their 50s or 60s faced with the challenge of making fresh plans for a later retirement in a lifestyle completely different to anything experienced by our parents and grandparents. But what does this mean for today’s undergraduates, graduates and those in the early phases of the world of work?

Or, even more importantly, for the child who started school recently and can reasonably expect that 100-year life span if all the science is to be believed?

Those were the issues the Council for Education in the Commonwealth (CEC) tried to tackle at its Autumn conference, bringing together in October a wide range of age groups and experiences – from undergraduates to retired educators.

Skills, not jobs

The conference was entitled ‘Commonwealth Horizons: Skills for the 21st Century’.

The clue was in the name – ‘skills’, not ‘jobs’.

CEC Chair Sonny Leong said that two billion jobs will be replaced by automation and artificial intelligence by 2030.

He said that the world of education and learning skills throughout a long life would be the key but that this path could not be left to chance. It is time, he said, to teach young people “how to learn” and be curious about their world to help them face a future that no-one can accurately predict.

“Education will be the key to opening up the new world of work to everybody,” Mr Leong said.

He added that the new world of self-selective “interactive learning” had to reach those who had been left out of globalisation.

In his keynote address, former UK Minister of State for Education and now Managing Director of online teaching site, TES Global, Lord Jim Knight, outlined how far education had changed in his lifetime alone.

Lord Knight pointed out how life had already changed from his grandparents’ days – characterised by the cycle of education, bedding down, 30 years of work and then retirement – already disappearing as a 20th century model.

With the prospect of 100-year old life spans, people now had a working life of around 60-70 years, Lord Knight said.

“What is the function of school?” he asked, questioning whether this was the time to look at moving to individual schooling which honed skills when needed during a longer adult working period.

He pointed out that corporations are already recruiting on skills rather than qualifications and that this “will pull the rug from under our qualifications system”.

What the market wants

These keynote comments resonated throughout the conference culminating in a final session on skills that companies today actually seek from graduates and others.

Scroll on to the end of the day’s deliberations and, the final plenary session, delivered by Dr Bob Gilworth, Director of The Careers Group at the University of London, who backed up the opening comments with research from the Association of Graduate Careers Advisory Services (AGCAS), of which Dr Gilworth is also Director.

He presented the skills base that companies are seeking now and for the near future, as assessed by the Association of Graduate Recruiters (AGR).

His message to the young hopefuls in the room was that the most important skill will be the ability to navigate in a changing world. He said that 82% of AGR member organisations do not specify subjects (apart from medicine and law) when recruiting.

Dr Gilmore listed a number of core skills gathered by AGR and from a survey of graduates who had been in the world of work for 2 ½ years including:

- Understanding the organisation you want to work for and its competitors

- Having a sense of yourself and what you bring to the organisation

- Showing an exploratory side, whether through work experience, volunteer work or any other avenue

- The capability to make and execute well-informed plans for the future

During the day, in another panel session, the Vice President of the Association of Graduate Career Advisory Services, Sue Bennett, had summed up the employability needs from today’s recruiters as “the message is that a degree is not enough…graduates need to stand out”.

A global education

Dr Gilmore might have been the expert but students and graduates had already been filling in the gaps during the day’s proceedings both as panel members and in questions and comments from the floor.

A panel on ‘Meeting the needs of students – expectations, aspirations and reality’ fuelled a lively discussion on the added value of universities which empower students to build skills outside the classroom and make themselves marketable.

The undergraduates and graduates spoke of being at university for “more than your books”, students pushing themselves out of their comfort zones, the need for better support for technical and vocational education skills training, the need for a global education and the breaking down of student clusters and silos on campuses.

The chances for the UK to up its game and tap into its international student base as a global resource also came up for discussion. A number of the students and graduates argued that the UK, and London campuses in particular, had not managed to achieve what many foreign students saw as the UK’s global USP of a multi-cultural education on campus.

“Digital students and analogue teachers”

It was not only student aspirations that came under fire but also the infrastructure to allow that aspiration to flourish.

A session on ‘What might be the skills for the 21st Century’ raised the issue of funding for skills training and continued education development.

Paul Nowak, the Deputy General Secretary of the UK’s Trade Union Congress (TUC), said that people could no longer let their education end after school or college. He argued for more lifelong learning for employees.

Comments from the floor also pointed to holes in the current education system, as one young woman, who won the applause of her peers, described it: “digital students and analogue teachers”.

Panellists repeatedly argued that too many children were being pushed into academia in a world running short on technical and vocational skills, about the need to get people involved in change rather than leaving them to feel that change is being imposed on them and how to fund people with more leisure time when there will simply not be enough jobs for human beings to do in the future.

One comment from a panellist on whether the world’s big software and information content providers should be better taxed to fund the new ways of learning earned some applause and had clearly opened up a line of debate for future discussion.

Life-long learning accounts

In the world of 30 to 40 years in the future where there will be no truck drivers and fewer GPs, participants tried to map out a skills horizon for a world where every industry will have felt the impact of software.

In summing up the day’s deliberations, CEC Chair, Dr Neil Kemp, pointed to the need to further explore new funding models for skills-based lifelong learning, the necessity of more discussions about and support for technical and vocational training and the need to teach flexibility to meet the skills challenges required for the 21st century.

The President of the Association of Colleges, Ian Ashman, had spoken during the day of the need to offer different modes of learning and ways to support educational institutions to allow for “lifelong learning” in a world where educational funding is currently provided “all at the beginning” [of life].

He pointed to the continued appetite for full time learning which now needed to work alongside more “flexible, part-time” education. He said that the Association of Colleges is looking at what they called “life-long learning accounts” with different forms of funding to allow people to dip into varied types of learning throughout their lives.

Employability in the 21st century, Dr Gilmore said at the end of the day, will come down to “the capability to make and execute well-informed plans for the future [and] to navigate an inevitably changing world”.

Lord Knight had called it in the keynote speech “educating for the knowledge economy”.

In a world, where the state would no longer be able to let people retire until 80, Lord Knight said that people would have to engage in what he called “your lifelong relationship with education”.

“We will now have lifelong learning at the heart of our human existence,” Lord Knight said.